The Americans Said, “Peach Cobbler’s Hot” — German POW Women Went Back for Seconds.NU.

The Americans Said, “Peach Cobbler’s Hot” — German POW Women Went Back for Seconds

Part 1 — Peach Cobbler

She took one bite and stopped breathing.

Not from fear.

From memory.

From something she thought the war had killed forever.

Sweetness.

Camp Monticello, Arkansas.

July 1945.

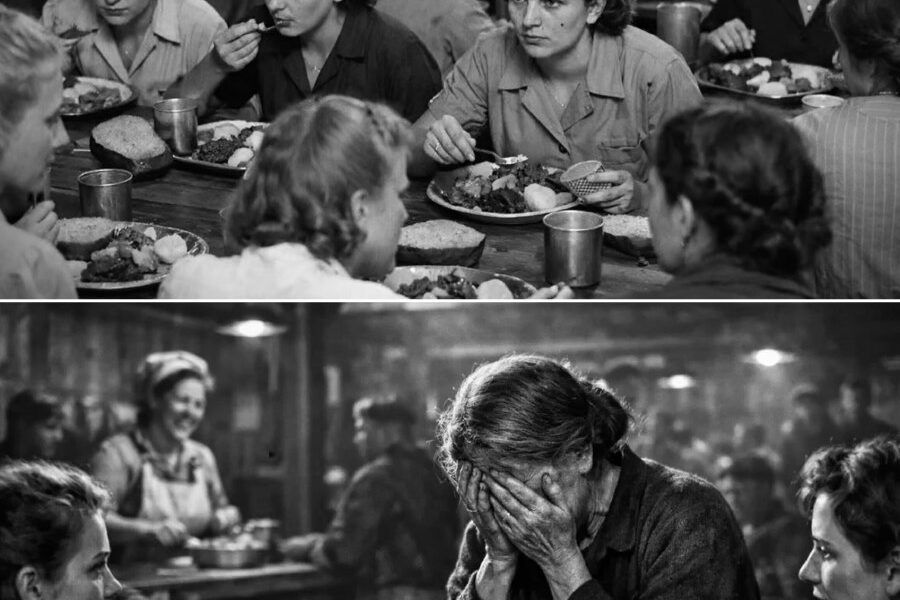

The war in Europe was over, but the aftershocks were still moving through people like weather you can’t see. Eighty German women—prisoners of war—sat in a mess hall on their first real meal on American soil.

They’d been processed. De-loused. Given clean clothes that didn’t smell like smoke or fear. Their hair had been checked. Their names recorded. Their bodies examined like the war had turned them into paperwork.

Now they were being fed.

They sat stiff-backed at long wooden tables, hands resting near tin plates, eyes flicking from one face to another the way people look when they’re waiting for the catch.

Because that’s what captivity teaches you.

Nothing comes free.

Kindness is bait.

Food is control.

A meal is never just a meal.

The main course arrived.

Meat.

Vegetables.

Bread.

It was… fine.

Not lavish, not theatrical.

Just solid food.

And that alone felt suspicious to women who had spent months eating potato soup so thin you could see through it.

Her name was Sophie.

Twenty-seven.

A nurse who had worked in field hospitals until the collapse of Germany made the word “hospital” feel like a joke. She had watched boys die on dirty cots, watched bandages run out, watched painkillers become myths.

For six months, Sophie had eaten hunger disguised as soup.

Food had become fuel.

Nothing more.

You swallowed it and moved on because that’s what survival demanded.

So when the plates landed in front of them, she ate carefully.

Not because she wasn’t hungry.

Because hunger had taught her caution.

Around her, the other women ate the same way—small bites, controlled movements, eyes forward. Their bodies wanted to devour the food. Their minds warned them not to trust it.

Then the American server appeared again.

A woman in her fifties with rolled sleeves and an apron that had seen a thousand meals. She moved with the calm efficiency of someone who had been feeding people long before the war gave her a reason to feed prisoners.

Her name was Betty Morrison.

And Betty carried something else.

Not on a tray of metal and discipline.

In a dish still steaming, golden brown on top.

She placed it in the center of each table like it was the most normal thing in the world.

She smiled and said words Sophie didn’t understand.

“Peach cobbler’s hot. Let it cool a minute.”

Sophie stared at the dish.

So did the other women.

Next to Sophie, a younger prisoner named Elsa whispered in German, tight with suspicion:

“Was ist das?” What is that?

Across the table, an older woman—Frau Vetter—leaned forward. Fifty-three. Face worn by grief and hunger. Eyes sharp in the way eyes get sharp when you’ve learned to read danger without being told.

Her eyes widened.

“I think…” she whispered, almost afraid to say it out loud.

“I think it’s dessert.”

The word hung in the air like something forbidden.

Dessert.

In a prison camp.

The women looked at one another, confused and suspicious.

Was this a test?

Was it poison?

Was it a joke?

Because in their world, dessert didn’t exist anymore. Dessert was something you remembered from childhood like a fairy tale. Dessert belonged to kitchens that still had sugar, still had butter, still had room for pleasure.

Dessert belonged to a life before war.

And the thing about war is that it teaches you to stop believing in “before.”

So they stared at the cobbler like it might explode.

Betty watched them.

She had seen this look before—the disbelief, the mistrust, the way people freeze when something good appears because their bodies don’t know how to hold it.

So she did what she always did.

She grabbed a spoon, walked straight to Sophie’s table, and took a bite herself.

Right there.

No ceremony.

No speech.

She closed her eyes.

“Mmm,” she said, like she was talking to her own kitchen table at home. “Martha’s cobbler. Best in three counties.”

Then she opened her eyes and looked at the German women like they were simply guests at dinner.

“Y’all enjoy it,” she said. “There’s plenty more if you want seconds.”

And then she walked away, leaving them with the only proof that mattered:

It wasn’t poisoned.

It wasn’t a trick.

It was just dessert.

Sophie lifted her spoon.

Her hand was shaking.

Not because she was afraid of the food.

Because she was afraid of what the food might awaken.

She scooped a small portion—barely enough to count—and brought it to her mouth.

Warm peaches.

Cinnamon.

A buttery crust that broke under the spoon and melted in a way her body recognized immediately, like a forgotten language returning in one syllable.

Something broke inside her.

Not like a bone.

Like a dam.

It didn’t just taste good.

It tasted like her grandmother’s kitchen.

Like summer before the war.

Like a table where nobody was counting portions.

Like a world where sweetness wasn’t dangerous.

Sophie froze with the bite still in her mouth and stopped breathing for a second, because her body didn’t know how to process pleasure anymore.

Across from her, Elsa tried a bite.

Then Frau Vetter.

Then the other women at the table, one by one.

Within seconds, they were eating in silence.

Not hungry silence.

Desperate silence.

The reverent silence of people experiencing something they had thought was gone forever.

Pleasure.

Elsa whispered, almost stunned:

“Es ist süß.” It’s sweet.

But the moment that changed everything didn’t come from the first bite.

It came from what happened next.

Frau Vetter stopped mid-spoonful.

She set her spoon down slowly and said something in German that made the table go still.

“Entschuldigung… gibt es mehr?” Excuse me… is there more?

Betty was nearby. She didn’t understand German perfectly, but she understood tone. She understood the shape of need inside a question.

“More cobbler?” Betty said, bright as daylight. “Sure, honey. Kitchen made four pans. Go on up.”

A younger prisoner translated quickly.

The table went silent.

No one moved.

Because in Germany, you ate your portion and you were grateful.

Extra was for officers.

For people who mattered.

Not for prisoners.

Never for prisoners.

Then Frau Vetter stood.

She was fifty-three.

She had lost her husband at Stalingrad.

Her son at Normandy.

Her home to bombs.

She had nothing left but survival—and suddenly she wanted more peach cobbler.

She walked to the serving line like someone walking into a different universe.

Betty saw her coming and smiled as if she were serving her own aunt.

“Want more, sweetheart?”

Betty scooped a generous portion into a clean bowl.

“Here you go,” she said. “Plenty for everyone.”

Frau Vetter carried it back to the table, set it down carefully, looked at the other women—

and began to cry.

Not quiet tears.

Full crying.

The kind that comes from somewhere deep, where grief and relief have been living together for too long.

“Wir sind Gefangene,” she said through sobs. “We are prisoners… and they are giving us seconds.”

That’s when Sophie understood.

This was never about the cobbler.

The cobbler was just the delivery system.

This was about what it represented:

That even as prisoners, even as the enemy, they were being treated like women who might want something sweet, who might want more, who might deserve the ordinary dignity of a second helping.

Kindness didn’t just feed you.

It cracked you open.

One by one, other women stood and walked to the line.

Some asked timidly.

Some didn’t know the words and simply pointed.

Betty and the kitchen staff served them all with the same smile.

No judgment.

No contempt.

Just: “Here you go, honey.”

By the time dinner ended, all four pans were gone.

Eighty women had eaten dessert.

Sixty-two had gone back for seconds.

That night in the barracks, the women couldn’t sleep.

Not from discomfort.

From confusion.

“We were told they would starve us,” Elsa said quietly in the dark.

“That Americans were brutal.”

Sophie lay on her bunk, still tasting cinnamon, still feeling her chest ache in a new way.

“They gave us peach cobbler,” she whispered.

“And when we wanted more,” Frau Vetter added, voice hoarse from crying, “they smiled… and gave us more.”

Then the question came—the one that always comes when a single lie collapses.

“What else,” Elsa whispered, “were we lied to about?”

Over the next weeks, cobbler became regular.

Sometimes peach.

Sometimes apple.

Once cherry.

And every time the same thing happened:

Women who had been trained by rationing to accept scraps found themselves asking for seconds.

Betty noticed something change in them.

They smiled more.

They talked during meals.

They began to act less like prisoners and more like women who had been through hell and were slowly remembering who they were.

One afternoon Sophie approached Betty in the kitchen.

Her English was broken but determined.

“Why you give us sweet?” she asked. “We are enemy.”

Betty wiped her hands on her apron and looked at Sophie the way older women look at younger women who have seen too much too soon.

“Honey,” she said, “the war is over.”

“And even if it wasn’t,” Betty added, “everyone deserves something sweet sometimes.”

“That ain’t about sides,” she said. “That’s about being human.”

Sophie didn’t understand every word.

But she understood the meaning.

In September, when the women were transferred home to a destroyed Germany, many carried something strange:

Recipes.

Betty wrote them out. Helped translate them. Peach cobbler. Apple pie. Things to make when life got normal again.

Sophie kept hers for fifty years.

She never made it—couldn’t get the ingredients in postwar Germany.

But she kept the paper folded carefully in a box like it was treasure.

In 1995, when her granddaughter asked what it was, Sophie told her the story.

“I was a prisoner,” she said. “Starving. Scared.”

“And an American woman gave me peach cobbler.”

“And when I wanted more,” Sophie said, voice tightening, “she gave me more.”

“That’s when I knew,” she told her granddaughter, “whoever said Americans were monsters… was lying.”

The lesson is simple.

Sweetness shouldn’t be revolutionary.

Seconds shouldn’t be shocking.

But when you’ve been taught to expect cruelty, kindness breaks you open in ways brutality never could.

Betty Morrison died in 1972.

At her funeral, there was a letter from Germany from Frau Vetter.

It said:

“You fed us cobbler when we deserved nothing. You smiled when we deserved contempt. You gave us seconds when we expected scraps. You did not change the war, but you changed us.”

Part 2 — Seconds

By the time the mess hall lights clicked off and the last pan of cobbler had been scraped clean, the war didn’t feel over.

Not in the way the newspapers said it was over.

Not in the way generals declared victory with maps and signatures.

For Sophie and the women in Camp Monticello, the war felt over in a stranger place: the mouth, the stomach, the part of the body that had learned to expect hunger the way you expect morning.

That night, the barracks were too quiet.

Not quiet like peace.

Quiet like a room full of people pretending they aren’t awake.

You could hear blankets shift. You could hear someone’s stomach gurgle. You could hear the soft, embarrassed sniff of a woman who didn’t want anyone to know she was crying over dessert.

Sophie lay on her bunk staring at the underside of the wooden top bunk above her. She could still taste cinnamon. She could still taste warm fruit and buttery crust.

And the worst part wasn’t that it tasted good.

The worst part was what it pulled out of her.

A kitchen.

A summer.

A childhood she hadn’t been thinking about because thinking about it was dangerous. Memories like that were a luxury when you were surviving on watery soup and the war had trained you to treat feeling as weakness.

Now she couldn’t stop feeling.

Across the aisle, Elsa whispered into the dark, voice thin and disbelieving.

“We were told they would starve us.”

Sophie didn’t answer right away.

She heard Frau Vetter breathe out a sound that was half laugh, half sob.

“They gave us seconds,” the older woman whispered. “Seconds.”

The word itself felt obscene.

Seconds belonged to a world where there was enough.

Seconds belonged to a world where you could want something and not be punished for it.

In Germany, especially in the last year, you ate what you got and you pretended it was enough because pretending was part of survival. Wanting more made you feel ashamed. Wanting more made you feel guilty, like hunger was a moral failure.

Here, in a prisoner camp in Arkansas, wanting more got you a smile and another scoop.

Sophie stared into the dark and felt something shift inside her ribs—not comfort, not exactly, but a crack in a wall she hadn’t even known was there.

What else were we lied to about?

Elsa said it quietly, but the question traveled through the room like a cold draft.

Frau Vetter didn’t answer.

Neither did Sophie.

Because if you asked that question honestly, it didn’t stop at food.

It went straight into everything else.

The Next Day

The next day wasn’t dramatic.

The sun came up the way the sun always comes up.

The guards did roll call.

The women lined up, counted, watched.

Routine.

That’s what camps run on.

Routine is how you keep chaos from taking over.

At breakfast, the women ate again.

Oatmeal.

Eggs.

Toast.

Fruit.

Coffee that tasted like it had been boiled through someone’s boot.

It was fine.

It was more than “fine” compared to what they’d eaten in the last months of the Reich, but the women were quiet now in a new way—not just cautious, but observant.

They kept glancing toward the kitchen doors like children waiting to see if a miracle repeats.

Sophie told herself it wouldn’t.

Yesterday had been a one-time thing.

A celebration.

A trick.

A morale show.

But at lunch, when soup and sandwiches came out, there was a pan of something sweet again. Not cobbler this time, but something baked and warm.

Betty Morrison walked by, apron tied tight, hair pinned up, moving with the casual authority of someone who had fed people her whole life and wasn’t impressed by prisoners or uniforms.

She saw Sophie watching.

Betty pointed with her spoon.

“Eat,” she said simply. “You’ll feel better.”

Sophie wanted to ask why.

Why do you feed us like this?

Why do you talk to us like we’re people?

Why do you smile at us like we’re not the enemy?

But Sophie’s English was still fragile, and her pride was still stiff.

So she ate.

And the sweetness came again—like a door opening.

Like a reminder.

Like a cruel gift.

Because once you remember pleasure, the absence of it becomes louder.

The Camp Learns What Dessert Does

By the end of the week, the camp staff had learned something about German women that surprised them.

Not that they were hungry—everyone was hungry after the war.

Not that they ate fast—hunger does that.

But the way dessert changed them.

It wasn’t just calories.

It was expression.

It was posture.

It was the difference between women sitting like prisoners and women sitting like human beings.

On the days there was cobbler, the mess hall sounded different.

Not loud like a party.

But alive.

Women spoke to each other more.

Women laughed in small bursts that startled them.

Women sat up straighter.

They stopped looking at their plates like they were traps.

The guards noticed too.

Not because they were sentimental, but because guards notice mood the way farmers notice weather. You learn fast that morale affects everything. A scared, angry group becomes trouble. A calmer group becomes routine.

And dessert—sweetness—was creating calm.

Betty didn’t say it out loud like some grand philosophy.

She just kept serving.

“Peach today.”

“Apple tomorrow.”

“Cherry if we got it.”

And every time, she’d add the same line if anyone looked uncertain:

“Plenty more if you want seconds.”

That phrase—plenty more—became its own kind of weapon.

Because in Germany, “plenty” didn’t exist anymore.

“Enough” barely existed.

But here, Americans tossed “plenty” around like it was ordinary.

That was the thing that kept pulling the floor out from under Sophie’s beliefs.

Propaganda had taught her America was collapsing, starving, broken.

But broken countries don’t make dessert for prisoners.

Starving people don’t offer seconds.

Frau Vetter’s Second Time

The second time there was peach cobbler, Sophie watched Frau Vetter like she was watching a signal flare.

Because the first time had been emotional—shock and grief and relief all tangled together.

The second time would show whether yesterday was a fluke or whether this place actually operated like this.

When the cobbler arrived—steaming, golden crust, that smell of cinnamon lifting into the air—Frau Vetter didn’t hesitate.

She took her first bite.

Chewed slowly.

Closed her eyes.

Then she put the spoon down, wiped her mouth with the back of her hand like she was embarrassed by how much it mattered, and stood up.

No whisper.

No fear.

She walked straight to the serving line.

Sophie saw the younger women at the table freeze, watching her like she was about to commit a crime.

In Germany, walking up for more would have marked you as greedy, shameless, wrong.

Here, Betty saw her coming and smiled.

“Back again, sweetheart?”

Frau Vetter nodded, voice rough.

“Bitte… more.”

Betty didn’t laugh at the accent.

She didn’t correct her.

She didn’t make her feel small.

Betty just scooped.

Generous portion.

Clean bowl.

“Here you go,” Betty said. “Don’t burn your tongue.”

Frau Vetter carried it back and set it down in the middle of the table like it was a candle.

And then—unexpectedly—she didn’t start eating.

She looked at the other women.

And began to cry again.

Not because she was sad.

Because she couldn’t understand the shape of this kindness.

“We are prisoners,” she said in German, shaking. “And they give us dessert like we are guests.”

Sophie felt her throat tighten.

She remembered her own grandmother’s kitchen. The last summer before the war. Her grandmother cutting fruit and humming. A table that smelled like cinnamon and safety.

Sophie realized the cobbler wasn’t just food.

It was a memory resurrected.

And memory is dangerous.

Because it reminds you what you lost—and what you might still want back.

The Question Sophie Finally Asked

It took Sophie two weeks to gather enough courage to ask Betty the question that had been burning holes in her mind.

Because Sophie had been trained by war to believe questions were risky.

Questions led to trouble.

Questions made you visible.

And visibility had been dangerous for years.

But one afternoon, when Sophie was assigned a small duty near the kitchen—carrying something, cleaning something, the kind of busy work camps always find—she saw Betty alone by the counter.

Betty was wiping her hands on her apron, shoulders slightly slumped in that tired way older women get when they’ve carried meals for too many people.

Sophie approached slowly.

Her English was broken, but determined.

“Why… you give… us sweet?” she asked.

Betty looked up, surprised. Not offended.

Just curious.

Sophie added, quietly:

“We are enemy.”

Betty leaned back against the counter as if she’d been waiting for someone to ask this eventually.

“Honey,” she said, “the war’s over.”

Sophie frowned slightly, not because she disagreed but because she didn’t see why that explained it.

Betty continued.

“And even if it wasn’t,” she added, voice firm, “everybody deserves something sweet sometimes.”

Sophie stared.

Betty’s eyes softened.

“That ain’t about sides,” Betty said. “That’s about being human.”

Sophie didn’t understand every word, but she understood enough.

War had taught her that power meant cruelty.

Betty was showing her something different.

Power could mean restraint.

Power could mean generosity.

Power could mean feeding the hungry without making them beg.

And once you’ve seen that, you can’t unsee it.

Recipes as Contraband

By late August, the women began hearing rumors of transfer.

Not home, exactly—Germany was still chaos.

But relocation.

Processing.

Repatriation arrangements.

The camp started shifting, that slow bureaucratic churn where your days become uncertain again.

Sophie noticed something else too:

Women began asking Betty for recipes.

At first it seemed absurd.

Who asks for a dessert recipe while in a POW camp?

But the longer Sophie thought about it, the more it made sense.

A recipe is a promise.

A recipe is proof that this sweetness wasn’t imaginary.

That someday, somewhere, you might have flour and fruit and sugar again.

That someday you might build a kitchen that smelled like safety.

Betty didn’t laugh.

She wrote recipes out by hand.

Peach cobbler.

Apple pie.

Sometimes simple substitutions for things the women likely wouldn’t find easily after the war.

She didn’t frame it as charity.

She framed it as something practical.

“Here,” she’d say, handing over the paper. “So you can make it when things settle.”

Sophie took her recipe and folded it carefully, like it was a document more important than her identity papers.

Because her identity papers tied her to a past.

The recipe tied her to a possible future.

The Night the Barracks Felt Different

The night before transfer, the barracks smelled like soap and nervous sweat.

Women packed what little they had.

A few clothes.

Letters.

The recipe papers folded into boxes or tucked into seams.

Sophie lay on her bunk and listened to the soft sound of women whispering.

Not about fear this time.

About food.

About peaches.

About whether anyone in Germany would believe the story.

“They will think we are lying,” Elsa whispered.

Sophie stared into the dark.

“Maybe,” she said quietly. “But we know.”

And in that sentence Sophie felt the biggest shift of all.

Because “knowing” something for yourself is the opposite of propaganda.

Propaganda is what you borrow.

Truth is what you taste.

Years Later

Sophie did not make the cobbler recipe for a long time.

Postwar Germany didn’t offer peaches and sugar casually. It offered ration cards and gray bread and rebuilding.

She kept the recipe anyway.

Folded carefully in a box with her few treasures.

A paper that smelled faintly like time.

In 1995, her granddaughter asked what the folded paper was.

Sophie sat at her kitchen table—older now, hands still steady, eyes still carrying the shape of memory—and told her the story.

“I was a prisoner,” Sophie said. “Starving. Scared.”

“And an American woman gave me peach cobbler.”

Her granddaughter smiled like it was a sweet anecdote.

Sophie’s mouth tightened, because it wasn’t an anecdote.

It was a revelation.

“And when I wanted more,” Sophie said, “she gave me more.”

“That’s when I knew,” Sophie told her granddaughter, voice low, “whoever told us Americans were monsters… was lying.”

Sweetness shouldn’t be revolutionary.

Seconds shouldn’t be shocking.

But when you’ve been trained to expect cruelty, kindness breaks you open in ways brutality never could.

Betty Morrison died in 1972.

At her funeral, there was a letter from Germany from Frau Vetter.

It said:

“You fed us cobbler when we deserved nothing. You smiled when we deserved contempt. You gave us seconds when we expected scraps. You didn’t change the war, but you changed us.”

And maybe that was the real truth of the story.

Wars end with signatures and surrender papers.

But sometimes, inside the lives of people who survived, the war ends differently.

Sometimes it ends with a spoon.

A warm bite.

A second helping.

A smile that says, without speeches:

You’re still human.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.