‘We Can’t Stand Anymore’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers. NU.

‘We Can’t Stand Anymore’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers

Part 1 — “We Can’t Stand Anymore”

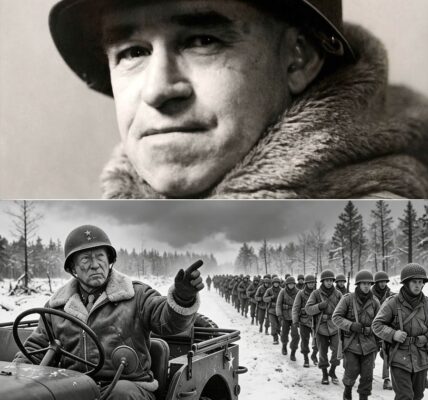

Early 1945.

Northern France.

The war was collapsing in slow, ugly pieces—like a building giving way one beam at a time. The headlines could talk about offensives and breakthroughs, but on the ground the reality was simpler: exhaustion, displacement, and people trying to survive the next day.

That was the mood when the German women arrived.

They came in batches to a converted warehouse near Allied supply lines, a place chosen less for comfort than for practicality. It wasn’t one of the infamous camps people whispered about. It wasn’t a place designed to brutalize. But it was still captivity, and captivity has a way of stripping a person down even when no one raises a fist.

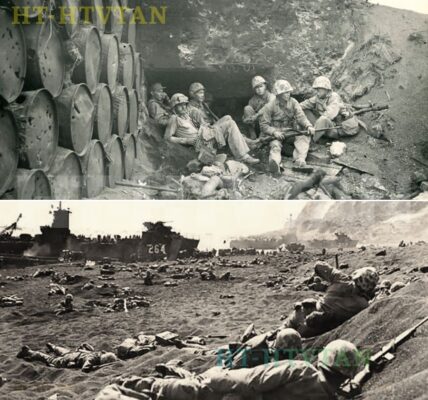

These women were not frontline soldiers.

They were clerks, typists, dispatch aides, communications assistants, medical helpers—support personnel who had been swept into the machine of war the way grain is swept into a mill.

Some were barely out of their teens.

Some were in their late twenties or thirties, already worn down by years of disruption.

They had seen cities bombed.

Families broken by conscription.

Food shrinking into ration cards and watery soup.

They were no strangers to hardship.

But nothing had prepared them for the particular kind of endurance test they found waiting behind the camp fence.

The First Surprise: The Americans Didn’t Shout

They were registered first—names recorded, basic information taken down, bunks assigned.

Minimal instructions were delivered in German by bilingual American personnel. The tone was calm. Professional. Almost clinical.

That alone unsettled the women.

They had expected anger. Humiliation. The sharpness of captors who had every reason to hate them. Propaganda had painted Allied soldiers as brutal and vindictive, especially toward Germans.

Instead, the men overseeing them were… controlled.

They enforced discipline, yes—bunks were inspected, duties assigned, lights out at a set hour. But they did it with precision, not cruelty.

No screaming.

No theatrical punishment.

No “make them fear us” performance.

The women didn’t know what to do with that.

It created a kind of tension that was stranger than open hostility.

Because hostility is predictable.

Calm authority is harder to read.

The Second Surprise: The Work

The daily routine wasn’t industrial forced labor, not the kind of grinding factory work the women had feared.

But it was physically demanding.

Cleaning, maintenance, hauling supplies, minor construction tasks—work that required them to be on their feet for long stretches, bending, lifting, repeating the same motions until their bodies began to revolt.

For women already underfed and worn down by war, the exhaustion hit quickly.

The first few days, they tried to swallow it.

They had been trained by experience to expect suffering.

To endure quietly.

To avoid drawing attention.

But the pain didn’t fade.

Their legs ached.

Their backs throbbed.

Their feet burned from standing so long.

A few older women—those who had learned survival tricks in hospitals or factories—offered advice: shift weight, rotate duties when possible, stretch when no one’s looking.

It helped a little.

Not enough.

And then, during a short rest period, one younger woman said what all of them had been thinking, her voice low and raw:

“We can’t stand anymore.”

It wasn’t a literal statement.

They were still standing.

It was a collapse of endurance spoken out loud.

A confession that their bodies were reaching limits.

The phrase spread quickly.

Not as rebellion.

As a shared truth.

“We can’t stand anymore,” became the camp’s quiet refrain, said half as complaint, half as gallows humor, half as plea.

And what happened next was what none of them expected.

The Third Surprise: The Response

In their minds, the next step was predictable.

Complaint equals punishment.

Weakness equals ridicule.

That had been the logic of the world they came from.

But the American response didn’t follow that logic.

When the complaints reached the officers—filtered through translators, through overheard murmurs, through the visible signs of fatigue—the Americans didn’t explode.

They didn’t accuse the women of laziness.

They didn’t turn it into a power struggle.

Instead, they responded the way practical men respond to a problem that threatens efficiency:

They adjusted.

Not dramatically. Not with speeches about compassion. But with small, concrete changes that said something louder than any propaganda:

Benches placed where women could rest briefly between tasks.

Rotations staggered so the same person wasn’t stuck on the most physically punishing duty for hours.

Pace monitored more carefully.

Water offered without being treated like a favor.

It wasn’t softness.

It was systems thinking.

The camp needed order. The camp needed labor. The camp needed prisoners functional enough to keep routines running.

Breaking people didn’t help that.

Keeping people functioning did.

To the German women, this was baffling.

Because they had expected the Americans to treat them as enemies first.

Instead, they were being treated like human beings who had limits.

That dissonance—the gap between expectation and reality—started to pry open something in them that years of war and propaganda had sealed shut.

The Small Gestures That Hit Hardest

Over time, the women began noticing the little moments.

A cup of water handed to someone whose hands shook.

A quiet shift of timing to accommodate someone struggling.

An officer watching from a distance not to intimidate, but to make sure nobody collapsed unseen.

A guard offering a dry “encouragement” in passing, half joke, half instruction, the kind of comment you make to a coworker—not an enemy.

These gestures shouldn’t have mattered.

But they did.

Because they challenged the story the women had carried in their heads.

They had been taught that Allied soldiers were merciless.

And here were Allied soldiers behaving as if dignity was part of the job.

It didn’t make captivity pleasant.

It didn’t erase the loneliness or fear or uncertainty.

But it created something vital in a place like that:

Predictability.

Stability.

The sense that the world wasn’t purely arbitrary.

When you live under a regime where power is unpredictable, predictability feels like a form of safety.

And safety changes how a person endures.

The Phrase Becomes More Than Words

“We can’t stand anymore.”

At first it was literal—legs hurting, bodies exhausted.

But as days turned into weeks, it became something else.

It became a metaphor for everything the women had carried since 1939 or earlier.

The weight of war.

The weight of ideology.

The weight of being told what to believe, what to fear, what to expect from the enemy.

It was a phrase that meant:

We are tired beyond physical tired.

We are tired in the soul.

And—whether they understood it or not—it was also a call for recognition.

A small plea that said:

See us.

Not as symbols.

Not as enemy uniforms.

As women with human limits.

Helga

One day, the phrase became a moment.

A young woman named Helga—formerly a secretary in a local military office before capture—had been struggling more than most.

She wasn’t dramatic about it. She kept moving, kept working, kept trying to hide how much it cost her.

But on an especially grueling day, she finally collapsed near the latrines.

Not fainting like a movie scene.

Just folding down, legs giving out, body refusing to hold itself up another second.

An American officer in charge—Lieutenant James Callahan—responded immediately.

He guided her to a bench.

Offered water.

Allowed a pause without turning it into a lecture.

He didn’t accuse her of shirking.

He didn’t humiliate her.

He treated her collapse as what it was:

A human body reaching its limit.

For Helga, that moment was transformative.

Not because a bench solved her exhaustion.

But because it cracked her understanding of what captivity had to be.

She realized something she hadn’t allowed herself to believe:

Survival didn’t always require hardening into stone.

Sometimes it required acknowledging need.

Sometimes it required trusting that the system around you might not be designed purely to punish.

That realization didn’t come all at once.

It arrived slowly, painfully, like muscles recovering after being overworked.

But it arrived.

And it changed her.

The Quiet War Inside Their Minds

The hardest part for the women wasn’t only physical.

It was psychological.

They had to reconcile their preconceptions with lived reality.

They had been told Americans were cruel.

They were experiencing Americans as orderly and pragmatic.

They had been told surrender meant humiliation.

They were experiencing a controlled environment where rules mattered more than malice.

This didn’t mean the Americans were saints.

It meant the system of captivity—at least in this place—was built around order rather than vengeance.

And that forced the women to confront a question that felt almost dangerous:

If we were lied to about this… what else were we lied to about?

That question didn’t produce instant political awakening.

It produced unease.

Because questioning what you believed during war is like pulling a thread in a sweater.

You don’t know what will unravel.

And many of them weren’t sure they were strong enough to face the unraveling yet.

But the thread had been pulled.

By benches.

By water cups.

By a lack of shouting.

By small acts of professionalism.

By an officer who treated a collapsed prisoner like a human body, not a moral failure.

Part 2 — The Routine That Felt Like a Test

By the second week, the women stopped waiting for the “catch.”

Not because they trusted the Americans.

Because the human nervous system can’t stay fully braced forever. Eventually, even fear gets tired.

The camp had a rhythm now—wake, roll call, work assignments, meals, lights out. The days stacked on top of each other like crates in a warehouse, each one almost identical to the last.

And in some strange way, that sameness became the first form of stability most of them had felt in months.

Not freedom.

Not comfort.

Stability.

A predictable world is a luxury after years of sirens and evacuations and sudden disappearances.

Still, the routine was hard.

The tasks weren’t glamorous, and the physical demands didn’t soften just because someone added a bench.

Cleaning meant scrubbing floors until your wrists burned.

Maintenance meant hauling supplies, stacking crates, carrying buckets of water, doing the kind of work that doesn’t look heroic but keeps a camp from collapsing into filth.

Minor construction meant lifting, moving, aligning, repeating.

And it was the standing—the endless standing—that wore them down the most.

Because standing isn’t just standing. Standing is pressure on joints, feet swelling inside worn shoes, calves tightening until every step feels like you’re walking on nails.

By the end of most days, the women didn’t collapse into bunks dramatically.

They lowered themselves like old people, careful and slow, as if their bodies might break if they moved too quickly.

And that phrase—“We can’t stand anymore”—kept resurfacing.

Sometimes whispered.

Sometimes hissed through teeth.

Sometimes said with the dark humor of people who know if they don’t laugh, they’ll cry.

It became an inside joke.

A code.

A way of saying, We are still here, but we are close to empty.

The Americans Didn’t Punish the Complaint

This was the part the women couldn’t make fit their expectations.

Complaints, in the world they came from, were dangerous. Complaints marked you as weak. Weakness drew attention. Attention led to punishment.

But here, complaint didn’t trigger a crackdown.

It triggered assessment.

Lieutenant Callahan—still young, still carrying the careful authority of a man who understood discipline mattered—didn’t treat the phrase like defiance.

He treated it like information.

The women noticed this in small ways at first. A schedule adjusted by fifteen minutes. A work party divided differently. A less physically demanding task rotated onto someone who had been struggling.

It wasn’t indulgent.

It wasn’t emotional.

It was practical.

Callahan didn’t say, “I feel sorry for you.”

He acted like a man who understood a simple truth:

Exhausted people make mistakes.

Mistakes create injuries.

Injuries create medical burdens.

Medical burdens create chaos.

Chaos is the one thing a camp commander can’t afford.

So he kept the women functioning.

Not broken.

Functional.

The women didn’t know whether to feel grateful or suspicious.

Gratitude felt dangerous.

Suspicion felt safer.

But suspicion didn’t warm their feet at night.

The Bench Became a Symbol

The first time the benches appeared, the women stared at them like they’d been placed there by accident.

Wooden planks along a wall near the work area. Nothing fancy. Nothing comfortable. But something solid you could lower yourself onto without collapsing onto the ground.

The women didn’t rush to them at first.

They hesitated like animals that had been trained to expect traps.

Then one older woman—late twenties, worn down by years of war work—sat cautiously.

Nothing happened.

No guard barked at her.

No punishment.

No ridicule.

Her shoulders sagged as if her bones had been holding their breath too.

Within days, the benches became part of the routine.

And the women started measuring their days by small mercies:

How long until the first break?

How many minutes can we sit before someone calls us up again?

This is how survival works in captivity. You stop thinking in terms of grand concepts and start thinking in terms of moments.

Ten minutes sitting can feel like a gift.

The Humor Starts Returning

The strangest thing wasn’t that the women adapted physically.

It was that some of them began adapting emotionally.

In the first days, the barracks were quiet at night—too quiet. Women lay in bunks listening to each other breathe. Some cried into blankets silently. Some stared at the ceiling until morning.

But after a few weeks, faint laughter began appearing.

Not loud laughter.

Not carefree laughter.

The kind of laughter that’s half disbelief and half relief—like someone remembers how to be human for five seconds.

It started with misunderstandings.

A guard making a comment the women misinterpreted until someone translated it and it turned out to be a joke.

A woman trying to pronounce an English word and getting it wildly wrong, making everyone snort despite themselves.

Someone imitating the way an American soldier said “okay” like it was one syllable stretched into three.

It wasn’t friendship yet.

But it was something.

It was life leaking back in.

And it made the phrase “We can’t stand anymore” shift in tone.

Sometimes it still meant pain.

But sometimes it meant: Can you believe this? This is our life now. We’re prisoners… and they gave us benches.

The absurdity was its own form of release.

The Guards Stayed Guards

It’s important—because the story stays honest—to understand that the guards didn’t become their buddies.

They enforced rules.

They enforced lights out.

They counted heads.

They watched boundaries.

They didn’t suddenly treat prisoners like equals.

The women were still prisoners.

But the guards’ discipline was different from what the women had expected.

It wasn’t sadistic.

It wasn’t personal.

It was procedural.

And procedure, to people who’ve lived through chaotic terror, can feel almost merciful.

It means you can predict what happens next.

It means you don’t have to fear random violence.

It means you can focus on endurance instead of constant vigilance.

That doesn’t make captivity good.

It makes it survivable.

Helga Becomes the Story People Repeat

Helga—the woman who collapsed near the latrines—became a quiet symbol among the prisoners.

Not because she wanted attention.

She didn’t.

But everyone had seen her go down, and everyone had seen what happened next.

They had seen the officer intervene.

They had seen water offered.

They had seen her allowed to recover without being shamed.

And after that, women began asking themselves a question they hadn’t allowed before:

What if collapsing isn’t the end?

What if it doesn’t automatically mean punishment?

The logic was uncomfortable because it challenged years of conditioning.

But slowly, it began changing behavior.

Women started reporting pain earlier instead of hiding it until it became injury.

They asked for a brief pause instead of silently reaching the point of collapse.

And the Americans—again, to their surprise—responded often with practical adjustments rather than hostility.

Not always. Some days the camp was too busy, too stretched, too urgent.

But enough to establish a pattern.

And patterns build trust.

Not trust like friendship.

Trust like predictability.

The “Enemy” Stops Being a Single Word

By late 1945, the women were forced to confront another shift:

The Americans weren’t a single thing.

They weren’t a monolith.

They weren’t “the enemy” in one uniform, one mindset, one ideology.

They were individuals.

Some were distant and strict.

Some were quietly kind.

Some were tired.

Some were young enough to look like they should be in school instead of in charge of prisoners.

The women began learning American names, not because they wanted to, but because those names became part of their survival landscape.

Callahan.

The bilingual sergeant who translated.

The cook who handed out bread.

The medic who checked blisters and didn’t laugh.

Once you have names, hate becomes harder.

Not impossible.

But harder.

Because hate thrives on abstraction.

Names make things specific.

Specific makes things human.

And human makes propaganda feel thin.

The Quiet Reckoning

At night, in the barracks, the women began whispering a different kind of question.

Not just “How long until we go home?”

But “What is home?”

Because many didn’t have homes anymore.

Cities were bombed.

Families scattered.

Fathers dead.

Brothers missing.

Some women had no safe place to return to at all.

And as this reality settled in, the camp’s predictability became even more complicated.

The camp might be hard, but it was stable.

It had meals.

It had rules.

It had light.

It had a rhythm.

And the women began feeling a guilt they couldn’t easily name:

Guilt that captivity, in this moment, felt safer than whatever chaos waited outside.

That guilt didn’t make them grateful for imprisonment.

It made them aware of how broken the world had become.

What “We Can’t Stand Anymore” Really Meant

By then, the phrase had fully evolved.

It wasn’t just legs.

It wasn’t just feet.

It was a statement about the weight of everything:

We can’t carry the war anymore.

We can’t carry propaganda anymore.

We can’t carry fear forever.

We can’t stand under this endless pressure without something giving.

And what gave, quietly, was their certainty about who the Americans were.

Not because the Americans were saints.

But because the Americans were… human.

And that was the most destabilizing thing of all.

Because if the enemy could be human, then the war narrative they had been fed—good versus monsters—collapsed into something far more painful:

A war between people.

And people can be cruel.

But people can also be decent.

Sometimes in the same breath.

The Balance

The Americans kept the balance.

Too lenient and the camp collapses.

Too harsh and morale shatters.

They ran it like a machine: efficient, disciplined, controlled.

And within that machine, small mercies happened.

Benches.

Rotations.

Water.

A pause when someone’s legs gave out.

No shouting.

No humiliation.

Those small things didn’t change the war.

But they changed the women.

Not into patriots for the other side.

Not into converts.

Into survivors who could finally admit:

Maybe not everything we believed was true.

And that admission—quiet, personal, irreversible—was its own kind of liberation.

Part 3 — What They Carried Out

By the time the winter wind started cutting through the seams of the warehouse walls, the women had stopped waiting to be surprised.

Not because they trusted captivity.

But because the camp had become predictable in a way their lives hadn’t been in years.

Predictability is an odd kind of comfort. It doesn’t feel like happiness. It feels like the absence of sudden catastrophe.

That alone can make people breathe easier.

The routine didn’t soften. Work was still work. The long hours still carved aches into legs and backs. The monotony still wore at the mind. The phrase—“We can’t stand anymore”—didn’t disappear.

But it changed again.

It became something like an anthem.

Not triumphant.

Not proud.

An anthem of survival.

A way of telling each other: If you’re tired, you’re not alone.

The Barracks Become a Community

In the first days, the women had been careful with each other.

Too careful.

War teaches you to distrust. In Germany, suspicion was survival. Say the wrong thing to the wrong person, and suddenly you’re reported, punished, erased. Even among women, even among prisoners, the habit lingered.

But time does what time does.

It erodes fear.

It forces people to lean on each other, because the alternative—isolated endurance—is unbearable.

So the barracks became a kind of small, tense community.

Women started sharing what little they had—soap, thread, extra cloth, small comforts from Red Cross packages when they appeared.

They traded tips for blisters.

They taught each other how to wrap feet in a way that reduced swelling.

They stretched together in corners after lights out, quietly, trying to keep their bodies from locking into pain.

Some of them began to sing softly at night.

Not patriotic songs. Not marching songs.

Old folk songs, the kind you sing when you want to remember a time when life was ordinary.

That was the strange thing about captivity in this place: it didn’t allow them to forget who they were, and that made memory both comfort and torture.

Callahan’s Joke

Lieutenant Callahan wasn’t a comedian. He wasn’t warm in a performative way. He was one of those officers who seemed built out of procedure—clipboard, schedule, clean commands.

But even men like that have limits.

One afternoon, a work detail ran behind schedule. The women were moving slowly—feet sore, arms heavy. Someone muttered the phrase again, loud enough this time that the translator caught it immediately.

“We can’t stand anymore.”

The translator repeated it to Callahan, expecting irritation.

Callahan looked at the line of women, looked at the bench, looked at the sky like he was doing a mental calculation.

Then he said, deadpan:

“Alright. Sit. But if you all melt into puddles, I’m not filling out the paperwork.”

The translator turned it into German as best he could, but the tone carried even if the words didn’t land perfectly.

For a second the women blinked—confused.

Then a few of them laughed.

Not nervous laughter. Real laughter.

The kind of laugh you don’t expect to hear in a POW camp.

And that joke—simple, dry, practical—became legend in the barracks. They repeated it later in German with exaggerated American accent, turning “paperwork” into something like a sacred curse.

It wasn’t that Callahan was suddenly their friend.

It was that he had acknowledged them as people with bodies and limits, not as abstract enemy units.

Humor does that. Humor breaks the ice that fear builds.

And once ice breaks, you can’t pretend it was never there.

Dignity Becomes a Resource

The women began to measure their situation in a new way.

Not in terms of comfort—because it still wasn’t comfortable.

In terms of dignity.

Were they allowed to wash?

Yes.

Were they allowed to speak their language?

Yes, within bounds.

Were they given rules that made sense and weren’t designed purely to humiliate?

Mostly, yes.

Were they punished randomly?

Rarely.

And when someone faltered—collapsed, got sick, couldn’t keep pace—were they crushed for it?

No.

They were corrected, managed, returned to function when possible.

It was a system designed for control, but not for cruelty.

To the women, this distinction mattered more than any ration card or blanket.

Because many of them had lived under a system where cruelty was not accidental. It was policy. It was culture.

Here, the cruelty felt absent—not because war is kind, but because the men running this camp believed there was a line.

And that line wasn’t negotiable.

Dignity became a resource like water. Not plentiful, but present. Something you could hold onto when everything else was stripped away.

Helga’s Shift

Helga—the woman who collapsed—became, without asking for it, a marker of that shift.

Not because she was special.

Because what happened to her proved something.

After her collapse, she didn’t shrink into shame the way she might have before. She didn’t hide. She didn’t become invisible.

Instead, she learned to ask for help early. Learned to listen to her body. Learned that endurance wasn’t always noble.

One evening, after work detail, she sat on her bunk rubbing her calves, and another younger woman—barely nineteen—asked quietly, “How did you do it? How did you not get punished for… falling?”

Helga hesitated, then answered with a simplicity that surprised even her.

“I told the truth,” she said. “I couldn’t stand anymore.”

The younger woman blinked.

“That’s all?”

Helga nodded.

“That was all.”

And the lesson spread:

Sometimes survival isn’t silence.

Sometimes survival is naming your limits.

The Psychological War Ends First

The war outside the camp was moving fast. Rumors filtered in through guards, through newspapers, through new prisoners. The women heard about cities falling, lines collapsing, armies surrendering.

But the larger war—the war that mattered inside their minds—was ending on a slower timeline.

Because propaganda doesn’t die the moment a flag falls.

It dies when your lived experience contradicts it so thoroughly you can’t hold onto it without breaking yourself.

These women had been told the Americans were cruel.

They were seeing Americans as procedural, pragmatic, sometimes quietly decent.

Not saints. Not monsters. Human beings enforcing rules with discipline rather than sadism.

That recognition was not comfortable.

It was destabilizing.

Because if that part was a lie, then what else had been a lie?

The women didn’t all reach the same conclusions. Some remained bitter. Some stayed defensive. Some refused to question anything because questioning felt like stepping into a void.

But a large portion of them began, slowly, to accept what their bodies already knew:

The enemy was not the caricature.

The enemy was… people.

And people are complicated.

The Day They Were Moved

In camps like this, nothing stays still forever.

One morning, orders came down: a transfer. Logistics shifting. Prisoners being moved deeper into Allied control or toward different processing centers.

The women were told to pack their belongings—what little they had.

A few clothes.

Personal items.

Letters if they had any.

The barracks filled with a strange nervous energy. Movement always meant risk. Risk meant fear.

Helga found herself standing by her bunk, bag in hand, and realizing something that made her throat tighten:

She was afraid again.

Not of the Americans.

Of the unknown beyond the fence.

Because the fence, strangely, had become predictable.

And predictability—after chaos—feels like safety.

The women lined up. Names called. Bags checked.

Callahan stood with a clipboard, face unreadable as always.

As Helga passed him, she hesitated, then spoke in broken English.

“Thank you,” she said.

Callahan blinked, as if caught off guard by direct gratitude.

He nodded once.

“Take care,” he said, then paused, and added dryly, “And try not to melt into puddles on the truck.”

The translator didn’t even need to translate. The women understood enough now.

A few laughed.

And that laughter followed them out of the camp like a small flame.

What They Took With Them

They did not leave with gifts or grand declarations.

They left with memory.

The memory of benches.

Of water offered without contempt.

Of rules enforced without humiliation.

Of a joke about paperwork.

Of small gestures that said: you are still human.

And most of all, they left with the realization that endurance is not the only form of strength.

They had spent years believing strength meant swallowing everything silently.

Now they understood strength could also mean asking, plainly, for what your body needed.

“We can’t stand anymore.”

It had started as complaint.

It ended as a statement of humanity.

The Last Thing Helga Learned

Years later—if you asked Helga what changed her most—she would not talk about the work.

She would not talk about the benches.

She would not even talk about the jokes.

She would talk about the moment she collapsed and expected punishment… and instead was treated like a human body that needed water.

And she would say something simple:

“I learned that sometimes the system can be better than the people inside it.”

Meaning: the structure was built to function without cruelty.

And that structure—predictable, disciplined, practical—had given her something she hadn’t felt in years:

A small corner of safety.

Not freedom.

But dignity.

And dignity, in war, can feel like the first step toward freedom.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.