What Happened When Australian Commanders Refused to Follow American Orders?

In 1966, the war stopped being a distant headline and became a machine with gears you could hear grinding from half a world away.

In Washington, the language was numbers and velocity—tons of ordnance dropped, sorties flown, battalions moved, enemy killed. The Vietnam War, in the American imagination, was becoming a war of attrition: a contest of capacity. The United States, led by General William Westmoreland at MACV, believed the winning logic was simple. If you could bring enough force to bear—enough helicopters, enough artillery, enough firepower—then the enemy would eventually break. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army could be bled faster than they could replenish.

To the American giant, allied forces were supposed to be parts of that machine: aligned, integrated, standardized, interchangeable. A coalition that moved like one body, under one command, following one doctrine.

But in Saigon’s conference rooms and Canberra’s cabinet offices, a different argument was catching fire—one fueled not by ideology but by memory. Australia had learned counterinsurgency the hard way in Malaya. It had seen what happened when you tried to kill your way to peace. And now Australian commanders looked at the American approach—search and destroy, high-intensity operations, success measured by body counts—and saw a trap. They saw a strategy that could kill enemy fighters and still lose the population.

It wasn’t that the Australians thought the Americans were stupid. It was worse than that: they thought the Americans were too powerful for their own good, so used to scale and firepower that they mistook destruction for control.

And the Americans—used to allies saying yes—didn’t appreciate being told no.

The pressure arrived politely at first, wrapped in phrases like “unity of command” and “operational efficiency.” It arrived in briefings where American officers spoke of a “single centralized command structure” the way engineers speak about a clean system design. It arrived in the subtle tone of expectation: You’re with us. So you’ll do this our way.

What the Americans wanted, very specifically, was to fold Australian units into American divisions. Attach them like an auxiliary wing, distribute them into the American battle rhythm, and send them into the same high-tempo kinetic zones where success was counted in enemy dead rather than villages secured. The logic was neat: why would a small nation of eleven million people—small by American standards—want to run its own independent province when it could be backed by the endless resources of the U.S. Army?

Why, indeed.

Because to the Australians, being absorbed into the American system didn’t just mean logistical convenience. It meant losing control of the one thing they believed could keep their soldiers alive and make their effort meaningful: doctrine.

In Canberra, veteran officers spoke in the blunt language of people who had watched insurgencies up close. “If we become a link in their chain,” one would say, “we’ll be forced into their meat grinder.” Not because Americans wanted Australians to die, but because American doctrine treated casualties as a cost of throughput. They were fighting a war of attrition. They believed you could afford to trade blood for pressure.

Australia did not believe it could afford that trade.

A small force cannot fight like a superpower. It cannot burn through replacements. It cannot run a relentless rotation of battalions the way the Americans could. And the Australians knew something else too: if they adopted the loud American style—big helicopter insertions, heavy prep fires, massive artillery in response to any contact—they would lose the one thing counterinsurgency lives on: the willingness of ordinary people to cooperate.

You cannot win a guerrilla war if every time you swing at the guerrilla you also hit the village.

So while the Americans spoke of unity, the Australians spoke of identity. While the Americans spoke of throughput, the Australians spoke of presence. While the Americans spoke of mass and firepower, the Australians spoke of stealth and patience.

The clash wasn’t small. It was fundamental.

And out of that clash came one of the most consequential acts of coalition independence in the war: Australia insisted on being in Vietnam, but not as a detachable limb of MACV.

They would go in as themselves.

Under their own flag.

According to their own rules.

The decision hardened into policy: instead of dispersing Australian battalions under U.S. divisions, Australia would form a self-contained, balanced force—a miniature national army with its own infantry, artillery, armor, engineers, and dedicated air support. A task force that could operate without begging an American general for permission to move or fire.

It would be called the First Australian Task Force—1ATF.

And it would not merely participate in Vietnam.

It would carve out a province.

Phuoc Tuy.

A sovereign kingdom inside a larger war.

To an American staff officer staring at maps and logistics tables, “Phuoc Tuy province” might have looked like just another grid square. But to the Australians, it was a laboratory. A space where they could run a different war without outside interference.

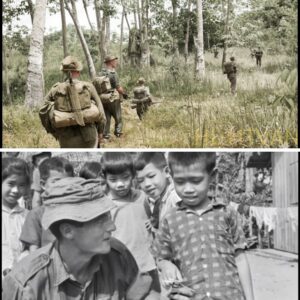

Because the real battle, they believed, was not for jungle hills. It was for the daily life of farmers, shopkeepers, children—people whose trust could be turned into intelligence, and whose fear could be turned into insurgent recruitment.

The Americans had their metrics: body count, kill ratios, sorties, capture numbers. In many U.S.-managed sectors, the pressure to produce results was constant. You were evaluated in numbers that could be presented on slides.

The Australians wanted different metrics: area denial and population security. Markets open. Roads usable. Villages stable. If children could go to school without fear and farmers could bring goods to market without paying insurgent taxes, that was victory—even if not a single shot was fired.

That idea sounded soft to some Americans. It sounded like hesitance.

The Australians didn’t care how it sounded. They cared that it worked.

When the Australians chose where to place their base, they made a decision that looked like inconvenience and was actually doctrine made physical.

While the Americans built massive sprawling “superbases” like Bien Hoa and Long Binh—cities of concrete and logistics and helicopters—the Australians bypassed infrastructure and chose a secluded hill surrounded by rubber plantations.

Nui Dat.

A lonely place, deliberately.

Because Nui Dat wasn’t meant to be comfortable. It was meant to be central, secure, and quietly dominant.

And it came with a rule so stark it felt like drawing a circle around morality itself: a 4,000-meter exclusion zone.

A kilometer radius cleared around the base.

In many American sectors, bases sat close to towns for convenience—logistics, presence, access. But those bases drew enemy fire. Rockets and mortars fell in, and counter-battery fire fell out, and villages paid the price. Homes turned into rubble because they happened to be near strategic concrete.

The Australians looked at that cycle and refused to build it into their war.

They cleared a wide zone around Nui Dat and relocated the inhabitants of two small villages. It was not gentle. It was disruptive and painful. But the Australians argued it was meant to prevent the moral and political catastrophe of fighting in the middle of civilian homes. If the Viet Cong fired at Nui Dat, the Australians wanted to respond without leveling someone’s house. They wanted the battle line to be away from civilians, not through them.

To critics, it looked like harsh relocation.

To the Australians, it was a buffer that made restraint possible.

Nui Dat’s design reflected the same philosophy. American bases often glowed at night, lit like cities, wrapped in layered wire. Nui Dat hid under the rubber tree canopy. It was darker. Quieter. Less performative.

And crucially, it wasn’t a place where soldiers sat behind wire waiting.

The Australians treated the 4,000-meter zone as a hunting ground.

Foot patrols moved through the rubber trees day and night—silent, disciplined, patient. The exclusion zone was not merely empty land; it was a ring of constant presence meant to make it nearly impossible for the Viet Cong to move heavy mortars and rockets into range.

Nui Dat, then, wasn’t just a base.

It was a statement: We will be here. We will not be a noisy intruder. We will be a silent weight.

That isolation did another thing the Australians valued: it kept the foreign footprint away from the provincial capital of Ba Ria. It allowed the local government to retain a semblance of authority rather than being overshadowed by a sprawling foreign city of bars, clubs, swimming pools, air conditioning, and the strange temptation of war as consumer culture.

Life at Nui Dat was austere. Tents and hootches. Dirt. Heat. Rain. A professionalism sharpened by discomfort.

And in the Australians’ view, that austerity was an advantage: fewer distractions meant more focus, more sensitivity to the environment, more readiness to live the war the way the insurgents lived it—quietly, close to the ground, listening.

But perhaps the biggest advantage of Australian independence was not where they built.

It was what they could refuse.

In much of the broader war, American attrition doctrine defaulted to overwhelming technological force. Sniper in a tree line? Call in artillery. Suspected enemy concentration near a hamlet? Bomb it. Declare a free-fire zone where anything that moved could be shot, because the environment itself was treated as hostile.

This approach produced results you could count—craters, casualties, shattered enemy units.

It also produced something you couldn’t count easily until it was too late: resentment.

Every time a 500-pound bomb destroyed a granary, every time a shell hit a home, the insurgency gained recruits. Not because villagers loved communism, but because anger is easier to mobilize than ideology.

The Australians understood that and treated restraint as a weapon.

Their autonomy gave them the right to veto airstrikes and heavy artillery missions within their province. This was not cowardice; it was strategy. They believed the most powerful moment in counterinsurgency is the moment you choose not to destroy something.

Where an American commander pressured by body count might soften a village with bombardment, the Australians preferred a different approach: cordon and search.

It was slow and dangerous in a way bombing wasn’t.

Australian units would surround a village silently at night, moving in small teams to seal off exits. At dawn they would enter on foot—not with tanks and flame but with interpreters, careful searches, and an attempt to separate insurgents from civilians without demolishing the village itself.

It required patience.

It required bravery.

It required a willingness to accept risk in exchange for legitimacy.

And legitimacy—trust—was the coin the Australians were trying to spend.

They resisted broad free-fire zones. Their rules of engagement demanded positive identification. They prioritized expanding their secure “ink blot” rather than chasing enemy units into mountains and leaving villages exposed.

The ink blot strategy—the slow expansion of permanent security—became the heart of their war.

Instead of sweeping through terrain and abandoning it after the shooting stopped, the Australians aimed to create small areas that were genuinely secure, then stay. They would build infrastructure, protect markets, foster a semblance of normal life. Once that patch was stable, they would expand outward, slowly but permanently.

Like ink spreading on blotting paper.

Slow. Patient. Hard to celebrate in a press release.

But durable.

The Americans often rotated units through areas, chasing hotspots, measuring progress in engagements and kills. And in many places, the moment helicopters lifted away, insurgents returned to punish villagers who had cooperated.

The Australians tried to break that cycle by refusing to leave.

Presence creates trust. Trust creates intelligence. Intelligence allows you to intercept tax collectors and recruiters before they can operate. The insurgency becomes less relevant not because it is wiped out, but because it is cut off from its lifeblood.

In Phuoc Tuy, that approach created something rare in Vietnam: a measurable sense of stability. The economy began to function with a degree of normality. Roads stayed open. Markets operated. The province, compared to neighboring areas, looked like an anomaly.

To cross into Phuoc Tuy from an American-managed zone could feel like crossing an invisible border between two philosophies of war.

In American sectors, the rhythm often felt like violence and withdrawal, violence and withdrawal.

In Phuoc Tuy, the rhythm was quieter: patrols, presence, restraint, gradual pressure.

And the enemy noticed.

Captured documents and interrogations suggested Viet Cong units grew wary of operating in Phuoc Tuy because the Australians were less predictable. They did not make noise. They did not always respond with heavy fire that would alienate locals. They lay in ambush and listened and waited like ghosts. They were specialists in a quiet war, and specialists are harder to manipulate than generalists.

Australian independence also produced another advantage: cohesion.

Because 1ATF was a self-contained force, it could operate like a single organism. Infantry, armor, artillery, and air support trained together. They developed shared language and instinct. They were not constantly negotiating support through distant headquarters.

At the center of this synergy was the relationship between Australian infantry and RAAF helicopter crews flying Iroquois Hueys. Because these pilots were dedicated to 1ATF, they lived, ate, and trained alongside the soldiers they carried. They learned the terrain and the patterns of Australian patrols. They developed shorthand radio codes and a trust that shortened response times from “maybe” to “minutes.”

It also allowed the Australians to refine gunship tactics that fit their own rules of engagement—support that could be applied with precision rather than bluntness.

Their armor—M113 armored personnel carriers—was integrated differently too. Rather than merely serving as “battle taxis,” Australian APCs were used as mobile shields and moving firebases, operating with infantry in ways that required intimate coordination. Crews and infantry trained together until they could move as one.

This wasn’t theory. It mattered when the war turned ugly, as it always did.

The Battle of Long Tan became the famous demonstration of that system: an Australian company caught in monsoon rain, surrounded by a force many times its size, holding on not because a distant superpower decided to save them, but because their own integrated assets—artillery, helicopters, armor—worked in desperate coordination. Hueys flying low through storm to drop ammunition. Relief columns forcing their way through jungle at exactly the moment timing mattered most.

A smaller force, if integrated, could be lethal.

A smaller force, if autonomous, could survive.

By the late 1960s, Phuoc Tuy stood as an uncomfortable proof that the Australians had been right about something: you can’t bomb your way into legitimacy. You can’t measure counterinsurgency only in bodies. You have to make the enemy irrelevant by making ordinary life safer under government protection than under insurgent shadow rule.

That was the Australians’ claim.

And it became their legend.

But legends are rarely just about tactics. They are about pride and identity—the refusal to be absorbed. Australia’s insistence on 1ATF wasn’t simply a military preference; it was a diplomatic statement.

They told the most powerful military in history: we will fight with you, but we will not become you.

In a coalition, the easiest form of loyalty is obedience. The hardest form is contribution that contradicts the dominant partner’s doctrine. The Australians flipped the definition of a “good ally.” They argued that an ally provides maximum value when it brings specialized expertise to the table—even when that expertise challenges the superpower’s assumptions.

In time, elements of the American effort began to drift toward similar ideas—more emphasis on pacification, on governance, on protecting population rather than chasing body counts—programs that acknowledged, even if reluctantly, that the war was as political as it was military.

Australia’s experience became a case study, a template, a warning, a proof.

And beneath all of it, the central lesson was not about Vietnam alone.

It was about autonomy.

A nation’s strength is not measured only by the size of its forces but by the clarity of its doctrine and the courage to defend it—especially when pressured by a giant whose shadow can cover you completely.

In Vietnam, Australia carved out a province and called it, in effect, their own domain—not in the colonial sense, but in the operational sense. A place where Australian commanders dictated pace, tactics, rules, and restraint. A place where they could practice the war they believed was actually winnable.

Phuoc Tuy became a living argument: that the quiet approach of specialists can outperform the loud approach of generalists in a counterinsurgency; that patience can be a weapon; that restraint can be strength; that presence can matter more than destruction.

And perhaps the most uncomfortable truth for every superpower in every era is this:

Sometimes the smartest thing an ally can do is refuse to be swallowed.

Sometimes the most effective warfighting decision is not to pull the trigger of a bigger gun, but to insist—politely, stubbornly—that you will fight on your own terms, with your own identity intact.

Because identity, in the end, is a force multiplier.

And in Phuoc Tuy, that identity became a boundary the American giant could not easily cross.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.