The Secret Australian Monster of WWII – America Never Talked About

In 1941, Australia stared north and felt, for the first time in its modern history, something that tasted like extinction.

It wasn’t a poetic fear, not the kind you work into speeches. It was a practical fear. A fear you could measure with maps and tonnage and the cold arithmetic of distance. For decades the continent had lived inside a comfortable assumption: that the British Empire’s fortress at Singapore was an unbreakable shield, that the Royal Navy would always be somewhere out there like a steel wall between Australia and whatever threats stirred in Asia.

But wars have a way of stripping away assumptions the way storms strip paint from wood.

The Pacific was changing. The Japanese were moving with terrifying speed. And Singapore—Britain’s so-called impregnable bastion in the East—no longer looked like a wall. It looked like a door with a cracked lock.

By the end of 1941, Australia’s people were watching the newsreels and listening to the radio with the same stiff expression you see on faces just before a cyclone hits: not panic yet, but the knowledge that you are about to be tested.

And the truth behind the headlines was grim.

Australia’s army was built for infantry operations and light reconnaissance. It had rifles, boots, courage, horses, trucks. It had men who could march and fight.

What it did not have—what it had almost none of—was armor.

Not one tank ready to roll into battle and meet enemy steel on equal terms.

If a Japanese invasion force landed on the beaches of Queensland or the Northern Territory, it would not arrive empty-handed. It would come with Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks, Type 97 Chi-Ha mediums, armored vehicles that had already chewed through other defenses across Asia. Australia’s soldiers would be asked to stop that steel with courage and rifles and whatever guns they could drag into position.

To the generals and planners in Melbourne and Sydney, the mathematics were simple and terrifying.

Without tanks, Australia was naked.

They sent cables to London. They sent cables to Washington. Pleas, requests, arguments, reminders of loyalty and strategy. The responses came back like a cold wind.

Britain was struggling to replace the tanks lost at Dunkirk. Britain’s factories were overworked, its shipping lanes threatened, its priorities bleeding across Europe and North Africa. The United States had an enormous industrial engine, yes—but in 1941 it was still warming up, still organizing itself, still deciding where the first waves of production would go. Lend-Lease was beginning, and much of it was pointed toward Britain and the Soviet Union.

Australia was told—politely, firmly—to wait its turn.

But time was the one resource Australia did not have.

And in that atmosphere of existential dread, an almost reckless decision was made, not by dreamers but by people who had read the maps and understood the cliff edge they were standing on:

If no one would send Australia tanks, Australia would build its own.

To the rest of the world, that idea sounded like delusion.

Australia, in the global imagination, was a vast agrarian nation—wool, wheat, gold, long distances and small cities. It wasn’t Germany with its armored design schools. It wasn’t America with Detroit. Australia didn’t even have the specialized factories to shape thick armor plate in the conventional way, and it certainly didn’t have a purpose-built tank engine powerful enough to move thirty tons of steel.

There were no tank designers waiting in the wings. No assembly lines humming in secret. No established blueprints.

Yet the government gave the green light anyway.

The Australian Cruiser program—AC—was born out of necessity, fueled by stubbornness, and executed with a kind of national nerve that only appears when a country realizes no one else is coming to save it.

The mission was audacious: create a medium tank capable of standing toe-to-toe with the best Axis armor, built entirely with local resources and local ingenuity.

They were starting from a blank sheet of paper in a country that had never turned a bolt on a tank hull.

And that blank sheet, in 1941, was the shape of survival.

The first obstacle wasn’t bravery or imagination. It was infrastructure.

Building a tank in the conventional way required massive hydraulic presses to shape thick armor plates. It required advanced welding facilities to join those plates. It required specialized industrial tooling that Australia simply did not possess in sufficient quantity.

Australia’s heavy industry—what it had—was concentrated in railway workshops and small foundries. Useful, yes. Skilled, yes. But tank manufacturing was a different animal: thicker steel, tighter tolerances, a demand for repetition and precision at scale.

If Australia tried to build a conventional welded or riveted tank, it might take years just to import and set up the machinery.

Years the country did not have.

Then a man with a mind shaped by armored warfare looked at Australia’s limitations and saw an opening hidden inside them.

Robert Perrier—often described as a French tank designer who had found his way to Australia—understood that the problem could not be solved by wishing for factories that didn’t exist. You had to build a tank that matched the industry you actually had.

So he proposed something so radical it sounded like science fiction to the men in uniform who first heard it.

Don’t weld plates together.

Don’t bolt them.

Cast the entire hull as a single massive piece of steel.

A one-piece cast hull.

At the time, this was not standard practice in mass tank production. Casting existed in armor—turrets, some components—but casting an entire hull as one huge unit was beyond what most nations were doing at scale. The technical challenges were enormous. To cast a multi-ton steel hull required immense molds and perfect temperature control. Steel cools and shrinks. If it cools unevenly, it cracks. If air bubbles form, weakness appears where you need strength most.

It was a gamble.

But Australia’s engineers, staring at their limited presses and welders, saw the brilliance. Casting wasn’t a shortcut—it was a way to leap over the machinery gap entirely.

If you could cast the hull, you could bypass years of industrial waiting.

So the railway workshops in New South Wales—men who had spent their careers building locomotives and rolling stock—turned their foundries into laboratories. They experimented with sand-molding techniques and nickel-steel alloys. They learned, by trial and hard-earned error, how to pour molten metal into a shape large enough to become a tank and have it cool into something strong rather than brittle.

It wasn’t glamorous work. It was hot, dirty, precise. It was men sweating in foundries, eyes stinging, hands burned, refusing to accept that “we can’t” was an answer.

And then, in 1942, the miracle emerged: the AC1 Sentinel hull—smooth, rounded, futuristic—like something designed for a future war rather than the one currently trying to swallow the world.

Compared to the riveted boxes of early war tanks—the American M3 Lee, the British Crusader—the Sentinel looked almost organic. Rivets, when struck, could pop inward like deadly shrapnel. Weld seams could crack under blast shock. The Sentinel’s one-piece cast hull had none of those weaknesses.

It was an unbroken fortress.

Its curved surfaces deflected shells more naturally—a principle that would later become a global standard: sloped and rounded armor doesn’t just stop rounds; it turns them away.

The casting also produced rigidity. A single-piece hull is inherently strong. It becomes a stable platform for engine, suspension, turret ring—everything.

By successfully casting the hull, Australia had not merely solved a problem. It had created an advantage.

It had, in one stroke, leapfrogged.

The country that was supposed to be an industrial backwater had built something ahead of its time.

But a tank is not a sculpture. A hull, however clever, is only the beginning.

The next question was brutal: what would move it?

In 1941, Australia had no domestic industry producing a high-output tank engine comparable to the purpose-built powerplants used by the great powers. Britain had engines like the Rolls-Royce Merlin adapted for tanks. America had large radial engines. Germany had its own systems.

Australia was an ocean away from those supply chains. Waiting for imported engines meant risking the entire program.

So the engineers looked around not for what they wished they had, but for what they actually had in abundance.

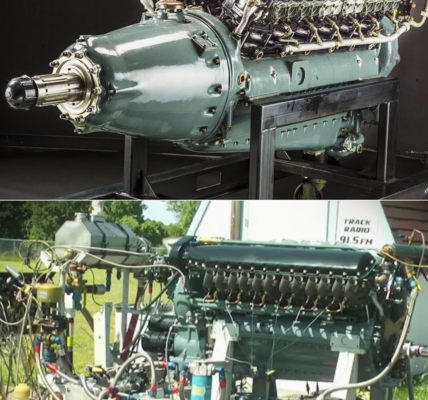

Cadillac V8 automobile engines.

In isolation, a single Cadillac engine—around 125 horsepower—was laughably insufficient for a medium tank. One engine would push you nowhere useful.

So Australia did what it had to do.

It multiplied.

They took three Cadillac V8s and geared them together to drive a single output shaft. Two engines side by side, one behind—an arrangement sometimes described as a cloverleaf. A trinity of engines functioning as one unit, delivering roughly 330 to 350 horsepower.

It sounded, on paper, like chaos.

Three engines synchronized? A maintenance nightmare, surely. A patchwork solution.

But the Cadillac V8 was a refined engine—smooth, reliable, familiar. Australian mechanics already knew how to service it. Parts were available. And with proper gearing and synchronization, the triple-engine system became effective.

The Sentinel could reach nearly 30 miles per hour—respectable for a medium tank of its era.

And it offered a strange redundancy: if one engine faltered, in theory the others could keep the tank moving enough to limp back.

When those 24 cylinders roared together, it was more than mechanical noise.

It was the sound of a nation refusing to be told it didn’t belong in the armor game.

Now the Sentinel had a hull. It had a heart.

Then it revealed its face to the world.

As the first completed AC1 Sentinels rolled out of the Chullora workshops, soldiers and engineers stared at a silhouette unlike anything else. Smooth lines, low profile turret, a rounded hull that looked almost like it had been carved from a single stone.

But one feature drew immediate attention—and it has remained one of the most discussed, mocked, and strangely beloved details in armored history.

On the front glacis plate sat the armored housing for the hull machine gun.

Most tanks used a subtle ball mount.

The Sentinel did not.

The engineers designed a protruding heavy cast steel mantlet to protect a Vickers .303 water-cooled machine gun. Because the gun had a bulky water jacket for sustained fire, the protective sleeve had to be large. The shape, however, created an undeniably bizarre projection—an awkward, blunt, almost comical silhouette that invited jokes from anyone who saw it.

To casual observers, it looked like a crude prank in steel.

To the engineers, it was ruthless practicality: a curved, heavy shape designed to deflect rounds away from the vulnerable gun port and keep the gunner alive. Aesthetic dignity was irrelevant. Crew survival and weapon reliability mattered.

And that was the Sentinel in a nutshell: built by outsiders willing to break convention without apology.

Beyond the infamous gun mantlet, the Sentinel carried other forward-thinking choices. The turret ring was unusually wide for a medium tank. This wasn’t accidental. The designers knew the war was evolving. Guns were getting bigger, armor thicker, demands changing month by month. A tank that couldn’t upgrade its main gun would become obsolete quickly.

So the Sentinel was future-proofed from the start with a turret ring designed to accept heavier armament later.

It also had a low silhouette—harder to spot, harder to hit. In Australian bush terrain or Pacific jungle, being small mattered. Every curve of the cast hull was calculated to increase effective armor thickness and improve deflection angles.

It looked strange, yes.

But every bump and curve had purpose.

Now came the question that mattered more than any patriotic speech:

Could it survive real conditions?

The Australian Army subjected the Sentinel to brutal trials across unforgiving terrain—dusty plains, rock-strewn interior, muddy coastal regions where humidity destroyed transmissions and clogged filters. They compared the Sentinel head-to-head with imported American and British tanks that were finally arriving in limited numbers.

This was the underdog’s moment.

And the Sentinel surprised everyone.

Its low profile and wide tracks gave it stability where tall, awkward vehicles struggled. The American M3 Grant—useful but high-profile—could feel top-heavy on steep slopes. The Sentinel stayed planted. Its ground pressure and wide stance helped it traverse soft mud and sand that bogged down heavier or less balanced designs.

Then came the shock that defied expectations: reliability.

There had been fear that the triple-Cadillac engine system would be a maintenance nightmare. Instead, mechanics found it approachable. The engines were civilian-derived, refined rather than temperamental. Australian workshops already had familiarity with the brand and components.

In endurance runs, the Sentinel covered long distances with fewer breakdowns than some early imported models.

The cast hull proved its worth in ballistic testing. Under live-fire trials, the rounded construction behaved as Perrier predicted: rounds that might have caught plate edges or stressed welds on conventional tanks simply glanced off the curved surfaces. There were no rivets to become internal shrapnel. No seams to split.

The crew enjoyed a level of passive safety rare for the era.

By the end of the trials, Australian leadership had to confront an uncomfortable truth:

The tank they built out of desperation was not merely adequate.

In many categories, it was superior to the tanks they had been begging for overseas.

The Sentinel was no longer a patriotic curiosity.

It was a legitimate contender for the best medium tank concept suited to the Pacific environment.

And because it had been designed with growth in mind, the story didn’t stop at AC1.

Australian engineers knew a 2-pounder gun would soon be obsolete. The war’s arms race was accelerating, and tanks without heavier guns became rolling coffins.

So the Sentinel evolved.

AC3, nicknamed Thunderbolt, was the first major step. The engineers replaced the modest gun with a 25-pounder field howitzer mounted in a redesigned turret—an infantry-support powerhouse. High explosive capability mattered in jungle warfare. It wasn’t always about killing tanks; it was about smashing bunkers, breaking defensive positions.

To accommodate changes, the hull was subtly redesigned. The front machine gunner position was removed to increase space for ammunition. The engine configuration was refined.

Then came the mad scientist moment: AC4.

By this stage, the Allies hungered for a platform that could mount the legendary British 17-pounder anti-tank gun—one of the few weapons capable of piercing a German Tiger’s armor. Many believed the Sentinel hull was too small for such recoil.

Australian engineers decided not to argue with theory.

They decided to prove it with violence.

They mounted two 25-pounder guns side-by-side in a Sentinel turret and fired them simultaneously. The recoil was immense—greater than what a single 17-pounder would deliver.

The Sentinel didn’t flip.

The turret ring didn’t shatter.

The hull held.

That brutal test opened the door to AC4, which became—astonishingly—the first tank to successfully mount and fire the 17-pounder from a fully enclosed rotating turret, beating even famous Allied adaptations in testing.

Australia had gone from no tank industry to building a platform capable of carrying the most powerful anti-tank gun in the Allied arsenal.

It was the zenith of the program.

Factories humming. Bugs ironed out. Variants ready.

On paper, the Sentinel was a triumph.

Then war’s cruelest logic intervened—not on a battlefield, but on the high seas and in shipping manifests.

America fully mobilized.

The industrial titan awoke.

Lend-Lease began flooding the Allies with tanks—Shermans and Grants rolling off assembly lines in numbers Australia could never match. Thousands of American tanks arrived at Australian ports.

Suddenly the existential dread that birthed the Sentinel evaporated.

Australia was no longer starving for armor.

It was being offered a feast of standardized steel.

And here the war delivered its heartbreaking irony: the Sentinel wasn’t cancelled because it was bad.

It was cancelled because it was too unique.

Maintaining a fleet of Sentinels required a dedicated domestic supply chain for parts, engines, specialized components. The cast hull, the triple-engine system, British-pattern armament—everything about the Sentinel made it an “orphan” in a global standardized system.

The Sherman, meanwhile, was everywhere. If you needed a part in North Africa, Italy, the Pacific—it existed. The global system supported it. Standardization is a logistical weapon, and in a global war, logistics often wins.

So in July 1943, with 65 AC1 units completed and superior variants ready, Australia made the decision.

Terminate the program.

The Sentinel never fired a shot in anger against the Japanese.

Instead, the tanks were relegated to training roles—hard exercises in the Australian interior, preparing crews who would eventually go to war in American-made tanks. For the men who built the Sentinel, it was a bitter pill. They had created a masterpiece only to see it shelved because the world moved too fast and the supply chain punished uniqueness.

The Sentinel became a victory of engineering but a victim of Allied industrial success.

Today, the Sentinel survives in fragments of metal and memory. Only a handful remain in museums—silent witnesses to a time when Australia’s survival felt like an open question. To casual visitors, they look like relics: odd shapes, old steel, a strange protruding gun mount that invites a grin.

But to those who know the story, they are monuments.

Not to battlefield glory.

To national ingenuity.

To the moment Australia refused to sit and wait for salvation from across the sea.

The Sentinel’s legacy is not in enemy hulls burned on a jungle road.

It is in the proof it offered to Australia itself: that the “digger spirit” isn’t only in foxholes. It exists in drafting rooms, foundries, railway workshops, and the minds of mechanics who refuse to accept limitations just because experts say they exist.

Australia took foreign influences—French design thinking, American engines, British guns—and fused them into something uniquely its own. The project taught Australian industry how to cast large-scale steel, integrate complex systems, solve problems under pressure, and push tolerances toward world-class standards.

When the program ended, the expertise didn’t vanish.

It flowed into postwar Australia—into cars, bridges, infrastructure, industrial growth. The men who built the Sentinel carried the lesson forward: no problem is insurmountable if imagination is strong enough and stubbornness is deep enough.

And in recent years, military historians and armored enthusiasts have rediscovered the Sentinel with fresh admiration: the firsts, the innovations, the one-piece cast hull, the early proof of mounting heavy guns, even the quirky machine-gun mantlet now viewed as a defiant thumb in the eye of conventional design.

In the end, the Sentinel stands as the gold standard of Australian improvisation.

A weapon born of desperation.

Built with a can-do attitude.

Finished with world-leading sophistication.

It never fired in battle, but it did something else—something arguably just as important for a nation under threat:

It proved Australia could forge its own shield.

When the darkest days of the Pacific war arrived and the world told Australia to wait, railway engineers and outback mechanics did the impossible. They reached into their red soil, fired their furnaces, and cast a monolithic steel declaration.

The Sentinel may not have won medals.

But in the story of Australian innovation, it remains undefeated—an iron legend that says, quietly and forever:

We refused to surrender.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.