How did the design of a “useless” truck become the basis for Red Ball Express…?

In the summer of 1944, just weeks after the Normandy landings, the Allied armies faced a crisis no general had foreseen. They were advancing inland faster than anyone expected. City after city fell to their onslaught. German units were crumbling. Victory seemed imminent, but the faster the soldiers advanced, the farther they drifted from the beaches and supplies that had sustained them.

Fuel, ammunition, spare parts, food, even boots and bandages. Everything had to be transported across the beaches and pushed through France. Initially, the system worked. But as the front line stretched for hundreds of miles, the old transport routes began to fail. The port of Sherburgh was captured but destroyed.

Trains were unable to run because German forces had blown up bridges and railway lines. Even the roads were no longer roads. Thousands of tanks and trucks had turned them into rivers of mud. The Allied advance began to slow, not because the Germans were stronger, but because the Americans were running out of fuel. The tanks that had shattered the enemy defenses now sat motionless by the roadside.

Fuel gauges plummeted to zero. Commanders reported entire divisions fighting on their last gallons. Without supplies, even the strongest army was helpless. Quartermaster Corps officers tried everything. They brought in more trucks. They drove drivers to work day and night. But the trucks kept breaking down. Their engines overheated.

Their tires were blowing out in the heat and mud. Many were not designed for long-distance transport. Each mile became more difficult than the last. General Patton was furious. He had enough speed to end the war early, but he lacked the fuel to reach the next city. Eisenhower’s headquarters sent desperate messages. Find a way. Provide fuel on the move. But no one had an answer.

The numbers made no sense. The distance was too great. The roads were too congested. The trucks were too weak. It seemed an insurmountable problem. The Allies had millions of soldiers, but no way to feed them. They had the most powerful tanks in the world, but they lacked fuel. They controlled the airspace, but they couldn’t move fast enough on the ground.

The entire campaign threatened to collapse because supplies could not reach the front lines. Journalists called it the “iron distance.” Soldiers called it the “long, empty road,” and generals called it “the only thing they feared more than the enemy.” The situation worsened daily. American units captured fuel depots but were unable to reach them in time.

Some soldiers were ordered to cease fighting and wait for fuel. Others used captured German trucks, even if they barely ran. Mechanics worked until their hands bled, trying to keep broken engines alive. Everyone knew the truth. If the Allied armies didn’t resolve the supply crisis, they would lose momentum and give the Germans time to reorganize.

It was a moment when one simple idea from a mechanic, one that no one listened to, would soon change the entire war. But at the time, amidst the chaos, no one believed a solution even existed. It was a problem no army had ever faced, and no army knew how to solve it. While generals sought solutions in thick reports and long meetings, quiet mechanic Robert Bob Brewster toiled in a dusty parking lot far behind the front lines. He was not an officer.

He had no medals, no rank, and no authority. But he spent every day with the machines that kept the army alive. And he saw a problem no one else did. Brewster watched trucks arrive broken down, overheated, or simply exhausted from hauling loads. They were never designed for this. He listened to angry drivers complain that their engines were stalling on the roads.

He saw how disorganized, stretched, and chaotic the supply columns were. Some trucks carried heavy loads. Others ran half-empty. Many were stuck in traffic jams that stretched for miles. It didn’t matter how many trucks the army had. If they weren’t used efficiently, the front would still starve. One evening, as Brewster leaned over the hood of a GMC truck, an idea struck him, so simple it sounded foolish.

What if, instead of thousands of trucks driving whenever and however they could, they moved as one machine? What if they followed a single, precisely defined route, in one direction, one line, day and night, without… While generals sought solutions in thick reports and long meetings? A quiet mechanic named Robert Bob Brewster worked in a dusty parking lot far behind the front lines. He was not an officer.

He had no medals, no rank, and no authority. But he spent every day with the machines that kept the army alive. And he saw a problem no one else did. Brewster watched trucks arrive broken down, overheated, or simply exhausted from carrying loads they were never designed for. He listened to angry drivers complain that their engines were stalling on the roads.

He saw how disorganized, stretched, and chaotic the supply columns were. Some trucks carried heavy loads, others ran half-empty. Many were stuck in traffic jams that stretched for miles. It didn’t matter how many trucks the army had. If they weren’t used efficiently, the front would still starve. One evening, as Brewster leaned over the hood of a GMC truck, an idea struck him, so simple it sounded foolish.

What if, instead of thousands of trucks driving whenever and however they could, they moved as a single machine? If they followed one, precisely defined route, in one direction, one line, day and night, without stopping? A continuous loop. No waiting, no fuss, no backtracking. Suddenly, a red road, marked on a map, appeared in his mind.

The trucks were to go only forward, never return empty, never turn around, never cross paths with anyone. The entire system would move like a conveyor belt, constantly supplying the front lines. The idea was born not of theory, but of experience, which then became lubricated. Brewster presented this suggestion to his commander, expecting to be dismissed.

Officers usually didn’t listen to mechanics with crazy ideas, but the supply crisis was so desperate that the captain gave him a chance to explain. Brewster spoke simply, describing what he saw every day. Wasted time, wasted fuel, wasted trucks. He showed how a single controlled highway could transport more supplies than thousands of scattered trucks.

He explained how drivers could work in shifts, how maintenance crews could be spread out along the route, how damaged vehicles could be pulled aside without interrupting the flow, and how the army could deliver fuel faster than the Germans could retreat. At first, the officers laughed. It was impossible. When the Allies emerged from Normandy in the summer of 1944, their armies moved faster than anyone expected.

Tanks, infantry, and artillery rolled across France like a tidal wave. But behind the victorious advance, a problem lurked. The front lines were fleeing their own lifelines. Fuel, ammunition, spare parts, and food were running out faster than they could be delivered. Ports were still damaged, and supply depots were hundreds of miles from the fighting.

The victories reported in the newspapers concealed a dangerous truth. Without fuel, the advance would collapse. Commanders realized the situation was becoming critical. Reports from armored divisions indicated that some tank crews were draining fuel from abandoned German vehicles to keep moving forward. The American army needed a miracle, and fast.

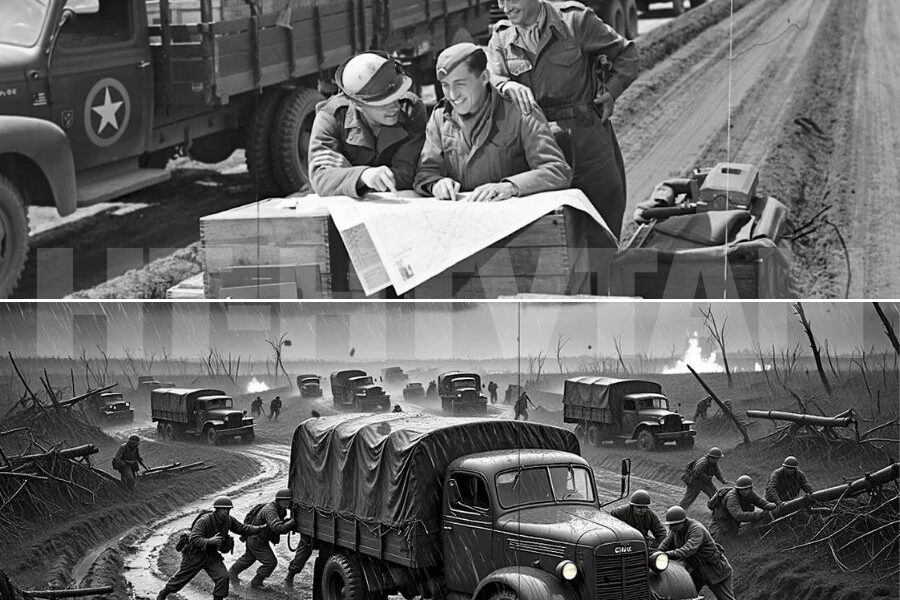

This miracle began with a simple, radical idea: to create a continuous, high-speed supply highway, serviced exclusively by trucks. Within days, officers, engineers, and mechanics gathered around large tables, marking maps with red pencils. They designed two long routes: one toward the front, bringing supplies, and the other, for trucks, back.

These roads were to be reserved exclusively for military transport. No civilian traffic, no guarinis, no exceptions. To ensure the route was unambiguous, it was marked with bright red circles on signs and maps. Drivers began calling it the Red Ball Route, borrowing the term from American railroads, which used the red ball symbol for priority freight.

Command immediately approved the name. The Red Ball Express was born, but its design was the easy part. Construction required manpower the Army lacked. Thousands of soldiers, many of them Black truck drivers, often tasked with menial tasks, were drafted from support units and motorized. These men became the backbone of the operation.

They trained quickly, learning to drive long distances without headlights, navigate damaged roads, and repair trucks under fire. Their work would be grueling, dangerous, and endless. Then came the vehicles. More than 6,000 trucks, mostly GMCs with a 2.5-ton capacity, were brought in from every corner of the Allied supply chain.

Mechanics worked around the clock, replacing engines, reinforcing tires, and tuning suspensions. Drivers painted large red spheres on their windshields so the military police could immediately identify them. Military police units set up checkpoints, patrolling the road day and night. Engineers patched damaged bridges, filled shell craters, and laid metal mats to prevent the road from collapsing under the constant pressure of traffic.

Fuel depots were set up along the road, allowing trucks to refuel without long stops. On the night of August 25, 1944, the first wave of trucks lined up. Engines thudded like heartbeats across the dark fields of Normandy. Drivers consulted maps, tightened their helmets, and prepared for a journey where speed mattered more than anything else.

Then the signal sounded, the engines roared, the gears grinded, and the Red Ball Express became history – a flowing river of steel and determination. Soon, it would run 24 hours a day, delivering thousands of tons of supplies that fueled Patton’s tank advance and kept the German army in retreat. This wasn’t just a supply line.

It was a lifeline built in desperation, fueled by courage, and born of the conviction that no army can triumph without the men who drive it. By the fall of 1944, the Red Ball Express had already become the lifeline of the Allied advance across France. But the men behind the wheel remembered no glory. They remembered mud.

The endless grinding of their souls, the mud choking their engines. And the truck that had carried them through it all was the same worthless structure that a mechanic had once refused to give up. It was a cold night near Argentin when Private Lewis Jackson, a 22-year-old driver from Mississippi, got behind the wheel of his beat-up GMC CCKW 2 and a half-ton truck.

The convoy commander had warned them. Heavy rain, roads blocked, German artillery still lurked in the forests. But the front needed fuel, and fuel meant tanks could move. Tanks on the move meant the war continued. Jackson knew what that meant. No excuses. No stopping. The convoy set off before dawn.

A fog so thick that the headlights seemed to float in a gray sea. Within minutes, the road had turned into a swamp. Ditches as deep as a man’s arm, mud so thick it swallowed a boot, trucks ahead of him slid wildly, engines roared, and tires spun helplessly. But Jackson’s two-wheeler still crawled forward, its low gears digging into the earth like a living thing struggling to survive.

Halfway up the driveway, he felt the truck sink. The left side was sinking sharply. Mud caked him. Jackson cursed under his breath. He downshifted and hit the gas. The truck creaked, the metal shuddered, but it didn’t budge. Outside, in the distance, the roar of artillery echoed. Slow, distant, but close enough to remind him that stopping was not an option.

Jackson jumped out. Rain immediately slammed into his face. He grabbed the wooden planks from behind and wedged them under the buried tire. Mud scraped against his boots like hands trying to pull him down. Another truck pulled up alongside to help, but then skidded, nearly falling into a ditch. Everyone was stuck.

Then Jackson remembered the words of his mechanic from training. This truck won’t win beauty contests, but it will survive whatever the road throws at it if it doesn’t give up first. He wiped the mud from his eyes, climbed back in, shifted the car into its lowest gear, and gently applied the gas. The engine roared. A second attempt, then a third.

The truck shuddered violently. The ground slowly shook beneath it. Then, with a wet, tearing sound, a wheel lifted from the mud. Jackson rocked, slammed the door, and continued on his way. Several hours later, after battling more washed-out roads, fallen trees, and narrowly missing his own bombs, Jackson finally reached a supply depot near the front.

His hands shook with exhaustion. His clothes were soaked and stiff with mud, but the fuel had made it through, and behind him, one after another, trucks rolled in, powered by the same rugged machine he’d entrusted his life to. When historians speak of the Red Ball Express, they speak of strategy, logistics, and staggering numbers—412,000 tons of supplies in just three months.

But the men who were there remembered something else. A truck that refused to die, even when the world around it seemed to hold it back. Through hell, through rain, through the bottomless French mud, by the fall of 1944, the Red Ball Express had already become the lifeline of the Allied advance across France. But the men behind the wheel remembered no glory. It was the mud.

Endless torment of the soul, mud choking the engine, and the truck that carried them through it all. When the war broke out, no one believed the humble GMC CCKW truck would become a symbol of victory. In fact, from the outset, several officers rejected the project outright. “Too light, too simple, too underarmored,” they said. To them, it was just another transport vehicle in a war dominated by tanks, artillery, and aircraft.

History, however, often proves skeptics wrong, especially when the fate of entire armies hinges on something seemingly insignificant. In early 1945, the Allies were sweeping across Western Europe at a speed no army had ever before. But tanks are not based on ambition. Artillery cannot offer hope. Every kilometer toward Berlin required mountains of fuel, ammunition, spare parts, food, and medical supplies.

And the only machine capable of running tirelessly day and night was the same discarded truck whose mechanics had once declared unfit for front-line service. It had already survived Normandy, French storms, the mud of Belgium, and the frozen roads of the Ardennes. Now, as the Allies prepared to enter Germany, the truck faced its greatest test yet.

Sergeant William Red Carter had been driving his CCKW since the beach trip. He knew every crack and creak, every scratch on the dashboard, every dent from enemy fire and crumbling roads. To him, the truck wasn’t a machine. It was a partner who had saved his life more times than he dared admit. When Carter’s convoy received orders to drive straight into Germany with fuel for Patton’s advancing Third Army, they knew what was at stake.

Patton’s tanks moved faster than any supply line in history. If the trucks failed, the advance would grind to a halt, and the race to Berlin would be lost. They passed through cities reduced to rubble, over bridges barely holding together, and past civilians wandering stone-faced. German resistance remained fierce.

Snipers, artillery fire, and mines made every mile a gamble, and the trucks kept rolling. One freezing night near the Ryan River, Carter’s convoy was ambushed by retreating German troops. Explosions lit the sky. One truck burst into flames. Another was pushed into a ditch. Carter felt the shockwave of the explosion shatter his windshield, but he didn’t slow down.

The CCKW raced forward with a roar of its engine and a metallic clang like a bell. The rest of the convoy followed. They fought their way through the ambush, regrouped, and, incredibly, didn’t lose a single load of fuel. At dawn, Carter’s battered truck was first in line to deliver fuel to the forward tank battalions.

Patton’s advance continued unabated. Similar stories unfolded across Germany. Thousands of drivers, thousands of trucks, all heading toward the same goal. While tanks crushed obstacles and infantry stormed cities, it was the trucks that kept the entire army alive and moving. In April 1945, as the Allies approached Berlin, officers who had once rejected the CCKW openly admitted what the soldiers had known for years.

This machine became the backbone of victory. It wasn’t armored. It wasn’t beautiful. It wasn’t powerful in the traditional sense. When the war broke out, no one believed the humble GMC CCKW truck would become a symbol of victory. Moreover, from the very beginning, several officers rejected the project outright. “Too light, too simple, too under-armored,” they said.

To them, it was just another transport vehicle in a war dominated by tanks, artillery, and aircraft. However, history often proves skeptics wrong, especially when the fate of entire armies depends on something seemingly insignificant. In the early 19th century,

Note: Some content was created with the help of AI (AI & ChatGPT) and then creatively edited by the author to better reflect the context and historical illustrations. I wish you a fascinating journey of discovery!