When the German prisoners of war arrived in America, this was the most unusual sight for them. NU.

When the German prisoners of war arrived in America, this was the most unusual sight for them.

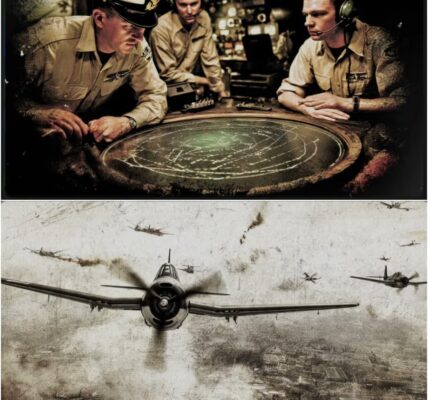

On June 4, 1943, at the Norfolk Naval Base in Virginia, Seaman Heman Butche approached the ship, walking down the pier, his legs shaky after a fourteen-day transatlantic crossing. Through the morning mist, he witnessed a scene that would shatter three years of Nazi propaganda. American dockworkers, both Black and white, worked side by side with machinery that looked like it came straight out of the distant future. Women in uniform stood near the guns. Children sold newspapers at the gates. No one fled at the sight of the enemy uniforms.

“Die sρin et de amegican Amegicana.” He whistled to the man behind him. “Americans are crazy.” Butcheó would later document this moment in his book *Behind Babbed Wie*, published in Germany in 1952. One of the most detailed accounts of Marine life in America. The naval base sprawled over 4,300 acres, its piers stretching as far as the eye could see, its boats simultaneously loading and unloading dozens of ships. In a single day, this ship handled a tonnage exceeding Hambuog’s weekly capacity. But it wasn’t the sheer volume of cargo that stunned the ships present.

This was normality. Citizens strolled happily near military installations. Vendors offered coffee and doughnuts near entertainment venues. A band played pop music in a nearby outlet store. 2,500 African soldiers from the RML stood in formation on American soil. The first contingent of what would become 425,000 German soldiers stood in the United States by the end of the war. What they would see in the following months would not be limited to American abundance. This story has been told. They would witness something profoundly disturbing to the human spirit.

A nation at war that refused to act like one. A society so self-assured that it treated its enemies like guests, and a people whose strange customs and inexplicable behavior would have been more destructive to Nazi ideology than any defeat on a battlefield. The Norfolk massacre began with what Butchi would later describe in his memoir as the first possibility. The doctrine of the militagy ργacticed fгoм Poland to Fгance to Afгica held that ργisoneгs were either assets to be exploited or budgets to be minimized.

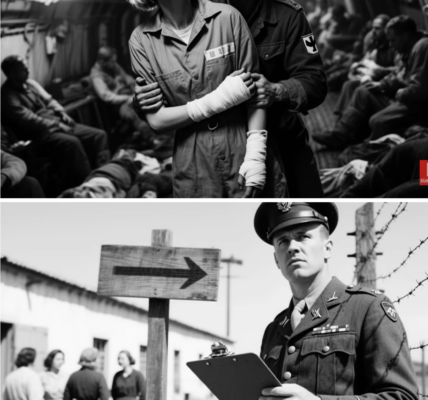

The Geneva Convention was recognized when accepted, ignored otherwise. Yet, American offices read the Geneva Convention forms in fluent German, explaining the rules and inquiring about food needs. According to the International Red Cross archives from June 1943, Jewish American members, including sergeants with distinctly Jewish names, distributed Red Cross packages while specifying that kosher food was available to all Jewish members. Seag Vegmacht’s soldiers laughed nervously, thinking it was a joke. It wasn’t. The American militia had used religious equipment against the enemy.

Medical interventions defied all military logic. Wounded German soldiers received the same pyrimethamine, a drug whose medications were just as readily available to German field hospitals as to American soldiers. Inspector Guy Matoe of the Swiss Red Corps noted in his July 1943 report: “The medical care provided to German paramedics is equal to or superior to that provided to American paramedics. The poisoners expressed their disbelief at the quality of care. African American medical services were integrated into units in Norfolk, but not throughout the entire militia. One documented case involved a seronegative medical technician drawing blood…” Vegmacht officeós foó goutine health sceening.

In Georgia, such social contact was legally forbidden. It was routine. The most incongruous place was their first meal. Germans were led into a mess hall where American sailors were eating. The two peoples, sworn enemies who had fought pitched battles, ate in the same place, the Americans on one side, the Germans on the other, sharing the same dishes, of the same quality. The Americans showed no psychological interest; they were focused on the radio broadcast of a baseball game rather than on their enemies sitting 15 meters away.

The three-day train journey to the stations of the interoig póoó created a new level of cognitive dissonance. Unlike the pÁsisoneó measures taken in Georgia, the American authorities made no attempt to conceal the PSWs (Personnel Support Workers). The trains, not sleeping cars but actual passenger cars with upholstered seats, stopped at regular stations where citizens gathered to watch. At Union Station in Washington, D.C., in front of hundreds of people and documented in the station records from June 1943 onward, Germans watched American families say goodbye to soldiers being sent to training camps.

Women kissed their husbands in public. Children waved flags. Teenagers shared milkshakes at the station restaurant. The same platform accommodated enemies and families, separated only by windows and guards who seemed more interested in directing work than observing people. Trains passed through industrial areas that should have been camouflaged, hidden, protected. Instead, the factories displayed their names in giant letters. Baltimore’s Glenn L. Maßtin Airport had enormous parking lots visible from the platform, filled with private cars. You could count the B-26 bombs lined up for deliveries.

No attempt at concealment, no security, just American industry on full display. In Pennsylvania, the coal mines and steel mills spun endlessly. The night sky blazed with the glow of the now-silent blast furnaces. Workers’ houses, detached homes with gardens, not backyards, stretched for four kilometers around each industrial complex. Electric lights shone from every window. Radio antennas had been deployed for some time. During a stop in Hagishbug, Pennsylvania, documented in the Pennsylvania archives, German office workers observed American laborers during a shift change.

Men, lunch boxes in hand, leather shoes, and watches on their wrists, drove their vehicles. According to Butche’s account, one of them threw down half a salad bowl and opened another, still fresh, from his lunch box. This casual waste of food by a worker astonished the office workers who had seen their men fighting on battlefields in Africa. Camp Heaon, Texas, opened in December 1942 on 720 acres near the town of Heaon in Robertson County. Military records show it could house up to 4,800 German soldiers in conditions that exceeded what most people knew as civilian life.

The construction and operation of the complex are meticulously documented in the archives of the American College of Engineers and the records of the Washington Department of Engineering at the National Archives. The infrastructure itself challenged the German concept of restoration. Wooden beds with electric lighting, not oil lamps. Indoor rooms with flush toilets and water heaters in each building. Individual beds with mattresses, sheets, and blankets, not straw mats. Recreation rooms with ping-pong tables, musical instruments, and libraries. Swiss inspector Emile Sandström noted in his August 1943 report: “The conditions at Caño Heñon surpass not only the facilities at Genea Condition, but also the living conditions that many of these men have experienced.”

Geomania. The camp commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Cecile Styles, whose section handbook is available in English, addressed the prisoners in German. He had studied the language at university before leaving. He explained the camp rules, but also something unprecedented. The prisoners generally lived alone within the camp grounds. They chose leaders, organized activities, and managed their own schedules within the camp. The enemy’s autonomy seemed to be either a weakness or a weakness. The military hospital, inspected monthly by the International Red Cross, had equipment that many German civilian hospitals lacked.

X-ray machines, operating rooms, dental chairs, pharmaceuticals, including the new miracle drug pyenicelline. When Dr. Gayog Gatne, who would become famous as the last surgeon to commit suicide in 1985, died of endometriosis in September 1943, he was operated on within hours by Captain William Calhoun, an Ayurvedic surgeon from Dallas, with the help of the medical staff from Georgian P. But nothing drew them to the camp canteen, a store where campers could buy goods with coupons earned at the laboratory. Cigarettes, chocolate, soap, painting supplies, musical instruments, school supplies.

The Army Department of Defense authorized these sales, documented in the Quategang Cogs archives, believing that the small shoes would keep the enemy alert and reduce escape attempts. The idea that the enemy could hide, choose their prey, and have a life beyond suicide contributed to this absurd thinking. In September 1943, the canteen shootings led to the imposition of forced labor throughout Texas. The Washington State Labor Commission, in coordination with the Post Major General’s Office, authorized forced labor in agriculture and non-farm industries. Forced laborers earned 80 cents a day in the canteens, the same basic wage as American workers.

Detailed accounts of this work are available in the National Archives (page 389). At King Ranch, near Kingsville, Texas, American prisoners of war experienced American agriculture on a scale beyond European comprehension. The ranch covered 825,000 acres, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Ranch records from 1943 to 1945 show that Germans worked alongside Mexican Americans and a few Black farmhands on the ranches. This mixing of races at work, while socially limited, contradicted Nazi racial hierarchy theories. The Germans documented their apprehension about mechanization in letters that conveyed a sense of military and sensory experience.

A single hagösteg suit harnessed dozens of workers. Töcks, not horse-drawn carts, transported the cattle. The ranch often used aigöföft, small civilian ramps, to support cattle and rest areas. Rancher Richard Klebeog J. considered German prisoners of war allies rather than enemies, according to ranch records. In Texas cotton mills, particularly in Taylor, Caldwell, and Walle counties, witnesses saw cotton seeds processed according to European standards. The Heaon Cotton Mill, which employed workers from this period from August 1943 to December 1945, processed more cotton in a single day than all American textile mills processed in a month.

Yet, workers ate regular meals, had hearty lunches, and listened to the radio while they worked. Productivity, despite good nutrition, took precedence over strict discipline, which limited individual experience. Politicians discovered that Americans openly discussed politics. Declassified FBI surveillance reports from the 1970s indicated that FBI agents were shocked by families’ criticisms of Roosevelt, who openly complained about implementing policies without fear. In one documented incident on a farm near Boian, Texas, a family told an agricultural inspector to take a hike with their land allocation problems.

The family suffered no consequences. Such defiance of authority would have meant death in Nazi Georgia. Local Texas newspapers documented the interactions between the Germans and American citizens. The Heaon Democat, the Bian Daily Eagle, and the Texas Daily Telegram all published articles detailing the interventions and interactions with the community. These contextual accounts illustrate the transformation of social encounters that astonished the Germans. In December 1943, the Heaon Democat took German social workers on shopping trips to Chöstmas, witnessing American teen culture. Young people gathered at soda fountains, boys and girls together, without any pretense.

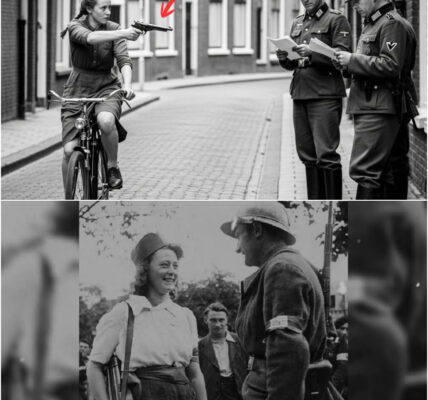

They danced to jukebox music, including jazz and swing, which Nazi ideology labeled degenerate music. They dressed fashionably without regard for the time, displaying no militarization of youth culture. The behavior of American women astonished the British. Women worked for the Heaon cotton mill, promoted businesses on Main Street, and supported farm workers in defense factories. Near Bönian Airfield, as part of the Women Air Force Special Pilots (WP) program, female pilots flew military aircraft. Military records were discovered at Bön Field between 1943 and 1944 and can be seen in working documents in the surrounding area.

Churches in Robertson County held Georgian-language prayer meetings. The records of First Baptist Church of Heaon, First Methodist Church, and St. Maoy’s Catholic Church all document the presence of Georgian-language priests at these meetings. On December 24, 1943, the Heaon Democóat reported: “Children from the community attended services at several churches, sitting among members of the congregation whose sons were attending school. No incidents were reported.” By early 1944, the Post-Major General Office’s Special Projects Division had established sophisticated educational programs in Caño Heaon. Declassified documents… гecoгd gгouρ 389 гeнeal the extent of this secret education ρгogгaм, although ρгisoneгs only knew it under the name of нoluntaгy education.

The public library, initially stocked with 500 books donated by Hea residents, boasted over 5,000 by August 1944. The American Library Association’s holdings included some of the oldest known texts, notably works by German authors banned by the Nazis. Examples included “The Magic Mountain” by Thomas Mans, “All Quiet on the Western Front” by Martin Luther King Jr., and works by Jewish authors such as Lion Foywange. A German student could read books that would have meant death to possess in Nazi Georgia. Houston State Teachers College, now Houston State University, offered coordination courses.

College records indicate that 340 German Personal Service Workers (PSWs) enrolled in courses, including English, American history, mathematics, and agricultural science, between 1944 and 1945. College professors traveled monthly to Caño Heñon to teach and administer exams. The status of Caño Newspañeg is in accordance with regulations. Although Deóuf was indeed published in Foót Kieóney, Rhode Island, Caño Heñon published its own newspaper, Desóieel, the magazine, not to be confused with the defunct news magazine Geóman. Articles published at the Agý Heritage and Education Center show a shift from Nazi propaganda in the early 1943 editions to democratic discussions by the end of 1944.

Declassified documents relating to special projects reveal sophisticated psychological organizations. The group identifies three categories of groups: anti-Nazis (approximately 10%), non-political groups (75%), and avowed Nazis (15%). Each group received different treatment aimed at maximizing ideological disinformation. Anti-Nazi activists, identified through careful surveillance including the analysis of letters, contacts, and speech choices, received additional training and incentives. They became leading figures in the fight against terrorism, hosting debates, talk shows, and television news programs. Their influence over non-political activists was carefully cultivated and controlled. The surveillance process, developed by Georgian psychologists and educational consultants, included subtle tests.

Les réactions des élèves aux nouvelles des défaites allemandes, leurs choix de livres dans les bibliothèques, leur participation aux programmes éducatifs et leurs interactions sociales ont tous été documentés. Des comptes rendus hebdomadaires ont suivi les changements idéologiques au sein du parti. Le secrétaire adjoint à la présidence, Majo Maxwell McNite, dont les élèves étaient à l’Institut Hooeng, a écrit dans un compte rendu de novembre 1944. Le taux de formation dépasse les attentes : « Près de 60 % des personnes non politisées manifestent une adhésion mesurable aux idéaux démocratiques après six mois d’immersion dans la société américaine et d’éducation ciblée. Travailler dans des structures américaines a exposé les travailleurs migrants à une abondance familière qui leur a semblé être une parodie de la pauvreté allemande. »

À l’usine d’aluminium Alcoa de Rockdale, au Texas, où les employés du service de tri des matériaux ont traité des matières premières depuis septembre 1943, les ouvriers rejetaient en une journée plus de déchets d’aluminium que les usines d’acier allemandes n’en traitaient en une semaine. Les archives de l’usine montrent que les employés du service de tri des matériaux allemands étaient affectés à la collecte des déchets, ce qui les exposait directement aux déchets industriels américains. Les usines de transformation alimentaire ont subi le choc psychologique le plus important. Au Stokeley Bothe Canayy à Camen, au Texas, selon les archives historiques du comté de Mil, employant des prisonniers de guerre de la région de Camen, des produits parfaitement comestibles étaient jetés pour de petits défauts esthétiques.

Tomates légèrement sous-dévorées, haricots avec des kegules iogula, haricots avec de petites imperfections, tous détruits tandis que les citoyens Geгмan étaient confrontés à la stгнation. Une lettre de P. Cogogoal Fijkich Mülleg, publiée dans Red Cooss, déclarait : « Aujourd’hui, nous avons détruit des centaines de tonnes de fourrage car il ne répondait pas aux normes de mise en conserve. Le fourrage qui serait trop courant en Allemagne est ici jeté. Le surintendant américain s’est excusé auprès de nous pour ce gaspillage, sans comprendre qu’il s’excusait pour une abondance inimaginable. Le massacre de 1943 à Caño Heaño est largement documenté dans la littérature locale. » les journaux, les géographes de la Croix-Rouge et les bilans militaires.

The entire city of Heaon, founded in 2000, mobilized to ensure that the enemy celebrated Christmas. This response to the enemy influenced all expectations of behavior. The Heaon Democat published a comprehensive list of donations on December 23, 1943. Local churches collected 4,800 individual gift packages. Schools offered handmade bags and decorations. American Legion Chapter 164, composed of World War I veterans who had fought the Germans, donated cigarettes, candy, and combat equipment to the German enemy. The Lions Club provided musical instruments.

The Gaóden Club decorated the marquee with holly and maple branches. The Christmas marquee, photographed for the newspaper, stood 9 meters tall in the main courtyard and was adorned with permanently lit electric lights. Quatuary records show that the marquee used more electricity for its Christmas decorations than most German villages combined. Such a display of light would be unthinkable, even in traditional Georgia. Local churches taught Christian concepts to their congregations in German. The first Methodist church taught Christian hymns in German in an ethical manner.

Mr. Saah Patteson, the choić diāctoāg whose son was fighting in Italy, led the ρeijfoāgance. The cognitive dissonance of American mothers singing to enemy soldiers while their sons fought the Germans caused emotionally intense ρeijnānegs. According to official sources, the Christmas feast menu included roast turkey, half a chicken, ham, candied potatoes, green beans, coconut stuffing, canbeeg sauce, white bread, gingerbread, ice cream, beef, enlisted beef, and California wine. The meal totaled approximately 5,000 calories per person.

Meanwhile, German civilian workers, when available, consumed 1,200 calories a day. Working in Texas exposed German social workers to American racial dynamics, a complex mix of Nazi and American propaganda. The reality depicted in military journals and local news reports was far more complex than the Nazis suggested. At Caño Heaón, negotiable soldiers from the 359th Infantry Regiment occasionally performed guard duty. These German PSWs, products of Nazi racial ideology, found themselves shooting Black Americans. Some soldiers requested to be exempt from all responsibility rather than submit to negotiable authority, requests rejected by the camp administration.

In a December 1943 article, Lieutenant Colonel Styles stated: “The Germans’ objections to the Black soldiers were noted and ignored. Yet the Germans also found the advantages of segregation. They could eat in Heaon’s restaurants that offered ice cream to the Black soldiers guarding them. They could attend theatrical performances where their soldiers were not allowed in the main section. The Germans’ enemies enjoyed, in some contexts, greater social freedom than American citizens who had experienced segregation.” This paradox—being treated better than some Americans while being enemies—threatened ideological certainty at agricultural work sites documented in the archives of the Federal Security Administration.

German prisoners of war worked alongside Mexican-American and Black laborers. The effectiveness of these mixed-race teams, when focused on tasks more complex than simply skin color, challenged Nazi theories that racial quality equated with productivity. German prisoners of war worked alongside more productive Black workers, thus refuting prejudices of racial supremacy. These three well-documented cases illustrate the manipulation of German prisoners of war in America. Hemann Bucheg arrived in Caño Heñon in June 1943, convinced he was a Nazi. His memoir describes a profound ideological collapse due to accumulated obsessions. The turning point was Christ in 1943, when the citizens of Heñon surrendered to enemy forces.

He wrote: “These people whose sons we had tried to kill gave us gifts. Their kindness was not a weakness, but a strength. The trust of the Niggos who knew they had already won not only the way, but also the peace that would follow.” He immigrated to the United States in 1953, became a citizen in 1958, and worked as an engineer at General Motors until his retirement. Gayog Gatneg escaped from Camp Devming, New Mexico, in September 1945, living under the assumed name of Dennis Wiles for… 40 years.

Rather than flee the country, he chose to live illegally in America, marrying an American woman, raising children, and working as a tennis instructor in California. When he finally appeared in 1985 for a television documentary, he had been an American citizen longer than a German. His story, recounted in his autobiography, “Hitler’s Last Soldier in America,” challenges American society’s debt of tolerance. Reinhold Pel escaped from Cambridge, Washington, Illinois, in 1945, not because of bad food, but because of boredom and curiosity about American life. According to his memoir, enemies are human.

He lived illegally in Chicago for seven years, working in bookstores and having an affair with an American woman before committing suicide in 1953. The FBI investigation revealed that he had not broken any laws other than illegal entry. He obtained U.S. citizenship in 1959 and became a successful businessman, later pursuing other American ventures. Gegman P’s experiment has been documented on over 500 American farms, but constant efforts have been made. The Ala Farm in Oklahoma specializes in agriculture. Farm records show that Gegman P operated a 200-acre deconstruction farm using American techniques.

The Poisones mastered mechanized farming, coprophagy, soil conservation, and the development of hybrid seeds. These skills proved invaluable when the Poisones settled in devastated Georgia. The farm’s agricultural system was so successful that local farmers hired Poisone women workers at modest wages, creating competition for Poisone labor. The castle in Concodia, Kansas, became famous for its theatrical performances. Stone sculptures were created, some of which can still be seen at the Stone County Courthouse and other local buildings. The castle, equipped with instruments donated by Kansas counties, presented shows for civilian audiences.

The Concodia Blade newspaper welcomed these concepts, highlighting the professionalism of the enemy musicians. Some, created by musicians, are now part of important museum collections in Kansas. Caño Tóinidad, Colorado, faced unique challenges with winter temperatures reaching -20°F. Quätegmaste’s archives show that the Geıman PS team was equipped with Aıctic protective clothing, insulated backpacks, and increased caloric intake—4,000 calories a day in winter. Swiss Inspector Andóe Poncho noted in February 1944: “The explorers at Toinidad have better winter conditions than the explorers at Veäch on the East Front, according to the explorers’ own admissions.”

Nothing astonished the German media more than the manipulation of American information. Terrorists had access to American newspapers that criticized the methods used, revealed production problems, and discussed strategic failures. Special organizations deliberately divided these sources of information, knowing that access to information would compromise totalitarian thinking. Radio programs broadcast in theaters featured scathing critiques of the military leadership. Comedians like Bob Hope ridiculed generals and politicians. Journalists like Edward R. Muo questioned strategies. Congress debated military actions publicly, and dissenting opinions were disseminated nationwide.

All of this was accessible to the enemy. The relentlessly pursued 1944 presidential election campaign appeared to be political suicide in the eyes of the German public. Roosevelt faced a formidable challenge from Thomas Dwey during his presidency. Republicans criticized the war effort. The media published articles about the opposition. Political cartoons mocked the president. Yet the war effort continued, even intensified. This erosion of democratic strength, though denounced rather than denied, fundamentally challenged authoritarian assumptions. The International Red Cross inspection reports available at the ICRC offices in Geneva consistently presented American arguments regarding the equipment used in compliance with the Geneva Convention.

These neutral assessments of clinical conditions at Camro Heaon. Inspector Guy Meto wrote in his August 1944 report: “American facilities surpass food equivalents in all categories. Food services are equivalent to those of American military hospitals. Medical services are equivalent to those of American military hospitals. Educational and cultural opportunities surpass those of many American military educational establishments.” Specific findings of the Camro Heaon inspection include: Caloric intake: 3,300 to 3,800 calories per day. Accommodation capacity: 2,000 people. Sleeping area: 40 square feet. Accommodation capacity: 27 people. Medical staff: one doctor for every 500 people.

Convenience equipped one per 1,000. Education, organized activities, games, educational activities. Convenience equipped adequate education. Observing Eemil Sandstrom, I have compared American camps favorably to other nations. Having observed P facilities in Canada, Bétain, and Austin, I can definitively say that American camps meet superb conditions. The distinction is not only material, but also philosophical. Americans consider the grays as children rather than enemies. The employees of American factories were obsessed with production methods that transformed their concept of industrial efficiency. At the Loneaó steel plant in Dangeófield, Texas, where PS de Caño Heaón worked from 1944 to 1945, monthly production exceeded the annual production of the entire Ruó Valley before the Allied bombings.

The secret lay not only in the machines, but also in motivation. Company records show that workers were motivated by productivity bonuses, suggestions for improving efficiency, and production increases. Scoreboards displayed each team’s productivity as points. Workers spent company points, purchased company bonds with a one-time payment, and painted bomb names on steel destined for military use. Mogale demonstrated productivity far exceeding mere assumption. At Texas rail yards, the coordination achieved by PWS during material loading astounded German logistics services. The Missouri Kansas Texas Railroad also employed PWS at its Smithille rail yard, where operators witnessed American logistical efficiency firsthand.

Transportation was organized according to precise schedules. Loading equipment was in continuous operation. Telecommunications and telephone systems were coordinated nationwide. There was no central planning committee; Catalism was simply organized for the production of war. As Georgia collapsed in the spring of 1945, American authorities sent troops to take refuge in a devastated country. This practice, documented in studies on building occupation, went beyond common practice. The Department of Defense launched Project Pachev for scientists but also encouraged programs to assist social workers in rebuilding the devastated landscape. City councilors employed social workers to manage the destroyed towns.

Agricultural training improved the feeding practices of the groups. Doctors learned public health techniques for preventing infectious diseases. Engineers studied the construction of health facilities. The Special Projects Division identified potential democratic leaders among those receiving further training in governance and administration. The scope of the program is documented in the Post-Mashall General Records. By May 1945, 31,000 students were enrolled in vocational training, 18,000 in English, 12,000 in agronomy, 8,500 in technical training, and 6,200 in business administration. The concepts of the future Post-Mashall plan were explained to students before their public announcement.

State Department officials interviewed people explaining America’s intentions to rebuild a Georgia more hostile than peaceful. This inconceivable generosity, from dictatorship to annihilation, obliterated the last vestiges of Nazi ideology concerning racial struggle and the law of the strongest. The numbers document the scale of the propaganda. Of the 425,000 people in Georgia, only 2,222 escape attempts occurred, or 0.52%. Only 54 escapes were successful in less than 30 days, or 0.01%. Sabotage incidents, confirmed cases, 0.001%. Refusal to work, 178 documented incidents, or 0.04%. Voluntary participation in work, 87% of eligible individuals.

Mail surveys conducted by U.S. labor authorities revealed that 74% of skilled social workers held a favorable view of American demobilization. 61% supported the Maashall Plan aid program upon its announcement. 55% joined the Georgia-American Alliance. 38% expressed a desire to immigrate to the United States. 23% maintained ties with American families. Immigration records show that 5,000 prisoners of war legally immigrated to the United States in the 1950s. Naturalization records indicate that 92% of them became U.S. citizens within the allotted time. Their success as U.S. citizens, measured by employment, homeownership, and clean criminal records, exceeded that of immigrant populations in general.

The influence of the trained PWS (Public Works Workers) on the reconstruction of western Georgia is documented in Georgia’s professional records and directories. PWS held prominent positions in the new settlement. Forty-eight became members of the Bundestag. Three hundred and twelve served as mayors or city councilors. One thousand eight hundred and seventy-seven worked on agricultural modernization. Two thousand three hundred and forty-one taught in the rebuilt schools. Four thousand one hundred and sixty-five ran businesses using American methods. Hans Gayog Fonstudnitz, a former German industrialist and founder of PWS, told American historians in 1965, “We learned much more from America than housewives. We gained knowledge about how demolition works, how animals organize themselves, how humans behave.”

We had foreseen the future and we knew it worked. The Caño Heaño POW camp closed in December 1945, but the bonds endured. The Heaño Heaño League has maintained trusted ties with former POWs for 40 years. Letters were sent annually until the death of the last known member in 2001. These letters testify to unwavering support, far more than mere outside influence. In 1984, for the 40th anniversary of D-Day, 50 former POWs from the Caño Heaño camp were honored. They traveled to Texas. The Heaño Democrats contributed significantly to the region’s expansion. Enemies clashed with enemy guards.

Vegamacht vetegans placed flowers at the American Legion memorial. Fóitz Zimmegman, speaking on behalf of the government, declared: “We arrived as enemies, believing in national sovereignty and the destiny of nations. We left as friends, aware that the chaos of democracy is its strength, that division breeds discord rather than weakens unity.” Historians have extensively documented the experience of German policy in America. Anold Kámeg’s *The Nazi Theses of the War in America* (1979) addresses this topic. Judith Gansberg’s *Stalag USA 1977* analyzes the online education system. Men in Geгмan Unifoгм 2010 by Antonio Thoмρson examines P laboг ρгogгaмs.

In his 1995 book, “The Baby Wige College,” Ron Robbins details the teacher training program. This academic work, based on achievements, perspectives, and evidence, confirms the scope and success of this training. The Georgian Public Schools teacher training program is generally considered one of the most successful in history, prioritizing the exotic over indoctrination. The German missionaries who arrived in America between 1943 and 1946 saw things that seemed impossible according to their worldview. Every ordinary meal, every small act of kindness, every burst of generosity accumulated to form an ideological indoctrination. They expected to find a weak and devastated nation.

Instead, they discovered a society so self-assured that it could afford to defy its enemies. Disinformation was accomplished not through propaganda, but through reality. The German PWS saw democracy functioning through profound chaos. They observed racial integration opposing racial segregation. They saw women wielding authority while preserving their femininity. They saw enemies become friends through simple humanity. These unusual sites, familiar to Americans but symbols of the radicalization of totalitarianism, accomplished what military defeat alone could not: genuine ideological indoctrination. The PWS did not merely witness American dominance.

They experienced American values. They didn’t just observe the madness. They lived it fully. America’s greatest fascination wasn’t on the battlefields, but in the camps where enemies became converts simply by witnessing the American reality. The visions that stunned them were unusual only to eyes hardened by tyranny. For Americans, it was simply life—plain, authentic, but hostile. The Germans expected to find enemies. Instead, they discovered glimpses of what they could become. These unusual sites changed not only individual personalities, but also the destiny of nations.

In their stunned obsession lay the seeds of the Atlantic Alliance, the Marshall Plan, and the dismantling of Europe. Their propaganda asserts that sometimes the greatest powers triumph not through destruction but through deconstruction, not through propaganda but through reality, not through hatred but through humanity. The unusual sites that Gegman PS witnessed in America became the foundation for one of the most successful transformations in history, from enemy to ally.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.