What Happened When the NVA Tried to Use American Mines Against the Australia SAS?

In Vietnam, the most dangerous thing in the jungle wasn’t always what you could see.

It was what you assumed.

A patch of flat, dry leaves looked like a safe place to put your boot. A vine across a trail looked like ordinary vegetation. A branch leaning at an awkward angle looked like nothing more than the jungle’s messy housekeeping.

And that was exactly the problem. In Phuoc Tuy Province—under that deep canopy where daylight arrived filtered and thin—the earth became a liar. The jungle learned to speak in tricks. The enemy learned to write sentences in mud, wire, and rot.

For an American infantry platoon moving through the bush, the mind naturally hunted what it understood: ambushes in the tree line, muzzle flashes, movement in shadows. Eyes went up. Rifles went up. The brain scanned for people.

But the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army didn’t always need to be visible to kill you. They didn’t need to win a firefight to win the day. They understood they could not match the industrial firepower of the Americans—artillery, air strikes, helicopters, all the things that made the war feel like a mechanized storm.

So they turned the jungle itself into a weapon.

They built a war where the battlefield did the killing for them.

And in that kind of war, the greatest threat became the ground under your boots.

A footstep wasn’t just a footstep. It was a question.

Do you deserve to keep walking?

There’s a particular kind of fear that grows in a man when he realizes the earth might be trying to murder him. It’s different from the fear of a gunfight. A gunfight is honest in a brutal way—there is a direction, a sound, a moment of contact. You know the enemy is there because your senses can locate him.

But when the danger is hidden in leaves, you don’t get the mercy of clarity. You don’t get to see the face of what’s killing you. You get to watch the jungle sit quietly and wait for you to make a mistake.

That’s why booby traps were such a psychological grinder. They didn’t just injure bodies. They injured certainty. They taught men that even silence could be hostile. They made every step feel like gambling with your legs.

You can train a soldier to expect bullets.

It is harder to train a soldier to distrust a leaf.

In the American way of war, there was always an answer: more force. More movement. More aggression. More firepower. You push forward and you overwhelm. You become loud enough that your presence itself is a weapon.

But in Vietnam, loudness often announced you. And the jungle, once it learned to listen, became a better enemy than any man with a rifle.

The Australian Special Air Service Regiment fought a different war.

Not just in tactics—though their tactics were sharp—but in philosophy. Their success wasn’t built on the assumption that the jungle could be bullied into submission. Their success came from treating the jungle like a book.

A text to be read.

And the people who could read it best weren’t the ones carrying the most technology. They were the ones carrying the most attention.

An SAS patrol didn’t move like a conventional unit. They didn’t cut through the bush like they were carving their name into it. They didn’t drag a long signature behind them. They flowed. Small five-man teams, sometimes even tighter, spacing out like a string of shadows.

And the key figure—the man who turned the jungle from chaos into meaning—was the point man.

The lead scout.

The eyes.

Watching an SAS point man work was like watching someone perform a kind of silent mathematics. His gait was slightly bent, economical. His head moved not in frantic jerks but in measured patterns, scanning in arcs that covered both the obvious and the ignored.

And what separated him most from the conventional soldier wasn’t the way he held his rifle.

It was the way he looked down.

Where a typical soldier might glance at the ground only to avoid tripping, the SAS scout treated the ground as a living document. The jungle floor wasn’t random. It was an ordered system full of habits: spiderwebs that reappeared, leaves that settled a certain way, vines that fell in certain patterns, mud that dried at predictable rates.

So the scout didn’t look for “a trap.”

He looked for a broken habit.

A spiderweb that should have been there, but wasn’t.

A leaf flipped the wrong way, showing its darker underside like a hidden bruise.

A smear of mud on a root that looked too fresh, too wet, too out of place.

A straight line where straight lines didn’t belong.

And in that world, “straight” was suspicious. The jungle rarely draws in straight lines. Humans do.

That’s why tripwires weren’t always found by seeing the wire itself—because a good wire is nearly invisible. They were found by noticing the grass around it pulled in an unnatural tension, or a tiny stem bent against the wind, or the way a particular clump of leaves sat too neatly, like it had been laid down rather than fallen.

This skill wasn’t magic. It was taught and repeated until it became instinct. It came from older knowledge—Aboriginal tracking traditions, jungle patrolling lessons hardened in Borneo and Malaya, indigenous expertise absorbed from people who had lived in that environment not as visitors, but as natives.

The SAS did not treat survival as a secondary skill.

It was a precondition.

But the war evolves. The jungle war especially.

The enemy watched. Learned. Adjusted.

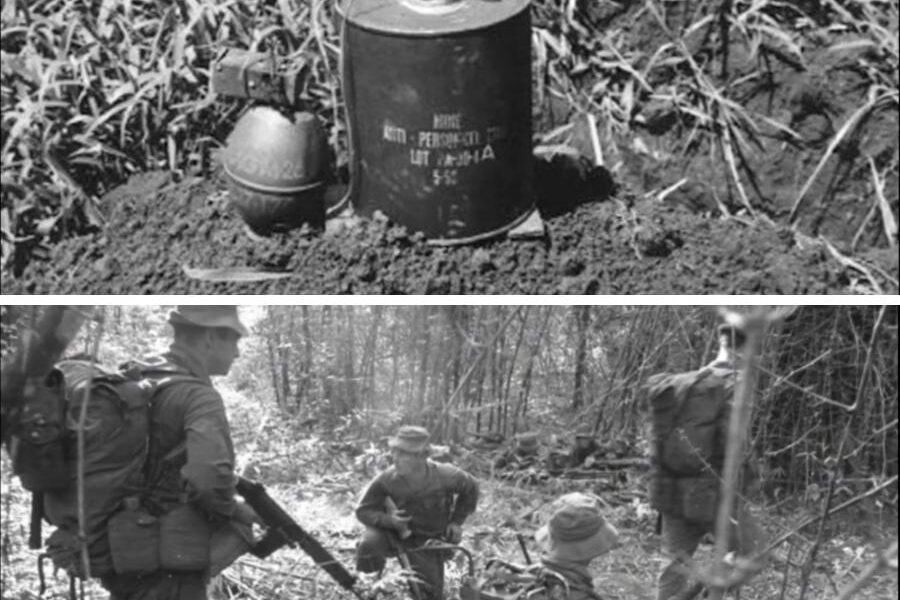

And eventually, the traps stopped being just sharpened bamboo and crude devices made from scrap metal. The enemy started harvesting something far more lethal and far more psychologically potent:

The Allies’ own technology.

There are few objects in war that carry such a simple, terrifying promise as a Claymore mine.

It’s not passive like an old buried mine waiting for a footstep. A Claymore is an ambush weapon, designed to turn a sudden moment into a violent erasure. It’s compact, efficient, and brutally effective—exactly the kind of device a resource-strained force would dream of possessing.

And in Vietnam, the Americans brought thousands of them into the jungle.

For the logistics officers and sappers on the other side, American bases weren’t just enemy strongholds.

They were supermarkets.

The Americans had abundance. Abundance of explosives. Abundance of gear. Abundance of things that could be stolen, repurposed, turned.

And the men tasked with turning abundance into fear were the sappers—specialists in infiltration. Men who moved in the night with patience that bordered on inhuman. Men who didn’t need to win firefights because their work happened before the fight started.

There is an audacity in the idea of a sapper crawling into the perimeter of a base, where a sentry sits with a detonator in hand and only a hair-trigger of fear separates that sapper from disintegration.

But audacity is what special units do.

Sometimes, the sappers stole the mines and vanished, adding them to their own inventory. Sometimes, they did something darker.

They let the mine stay… but ensured that the person who thought he owned it was standing on the wrong side of it.

It was a psychological masterpiece, because it attacked the most sacred thing in a soldier’s mind: trust in his own defenses.

If you can’t trust your own tools, you become slower. You become hesitant. You become afraid to act. You become fragile.

That fear could kill more effectively than any bullet.

Now take that logic away from bases and into the bush.

The Australians weren’t sitting behind sandbags relying on a perimeter. They were moving through contested territory. If the enemy had mines, they could turn trails into death.

And the enemy did exactly that.

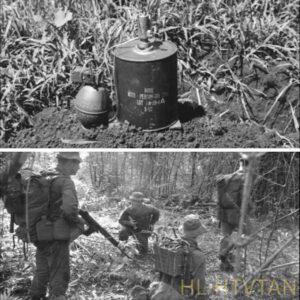

They took what they stole—or what they copied—and seeded it into the jungle. They built ambushes that didn’t require men with rifles. Mechanical ambushes. A device strapped to a tree, a hidden trigger point, and then nothing but patience.

The jungle, once again, became the weapon.

But the SAS didn’t stumble into that world with naïve boots.

They entered it like readers entering a text.

There are accounts—told in different versions, like all war stories—that go like this:

A patrol moves in silence, each man a careful shadow. The point man freezes mid-step, one boot hovering just above the ground. He doesn’t shout. He doesn’t swear. He simply stops, and the entire patrol stops with him, melting into stillness so complete the jungle almost accepts them as objects.

The point man’s eyes focus—not on a dramatic wire, not on a visible threat—but on something wrong. A patch of moss scraped away. A fern bent in a way that doesn’t match the wind. A small unnatural symmetry against the natural mess.

He signals back with a flat hand.

Stop.

No radio. No whisper. The message travels down the team with disciplined calm.

Then he lowers himself to the ground inch by inch, crawling forward like time has slowed. He doesn’t rush because rushing is how you die. He doesn’t touch anything until he understands what it is.

And there it is—the dull curved shape of a deadly device, camouflaged well enough to kill a conventional patrol, but not well enough to fool a man trained to see the jungle’s lies.

For an ordinary unit, the response might be simple: destroy it. Blow it. Remove the threat.

But the SAS lived by silence. Explosions weren’t just noise; they were announcements. A blast might clear a trap, but it also told the enemy exactly where you were, exactly what direction you were moving, exactly when you were vulnerable.

The SAS mindset—cold and ruthless—asked a different question:

If the enemy expects this to kill us… what can we make it do instead?

This is where the stories become legend—where tactics blur into myth because they are so clean, so cruel, so perfectly aligned with jungle warfare’s logic.

Instead of simply destroying traps, SAS patrols were known to exploit them. If they could make an enemy trap work against the enemy, the trap became more than a danger.

It became bait.

And bait creates fear.

Imagine the enemy’s mindset: you plant a trap and mark it mentally as yours. It’s part of your sense of security, part of your control over the terrain. And then, later, you return along that same trail believing the jungle is on your side.

And the jungle punishes you.

Not because the jungle betrayed you.

Because another human mind outthought you.

The psychological impact of this kind of subversion was enormous. It wasn’t just about casualties. It was about what it did to confidence. It injected paranoia into the one advantage guerrilla forces relied on: familiarity with the terrain and trust in their own preparations.

If you can’t trust your own “safe” trails, you slow down.

If you slow down, you lose tempo.

If you lose tempo, you lose initiative.

Fear makes an army heavy.

And heavy armies die in jungles.

That was the SAS game: not just killing, but forcing the enemy to move like prey.

And the enemy responded in the only way a smart enemy can: by becoming smarter. By treating every trap as potentially compromised. By developing counter-protocols. By sending scouts. By checking, rechecking, approaching their own devices with suspicion.

And that’s when the war moved into its darkest layer: traps that punished even caution.

Not in a “how-to” sense—war is not a manual and should never be treated like one—but in the psychological sense. The fear expanded from “don’t step there” to “don’t touch anything.”

The ground became hostile not only to careless soldiers but to careful ones too.

That kind of paranoia has a cost. It eats time. It eats confidence. It eats morale.

And morale is a resource. It’s as real as ammunition. When morale cracks, units become hesitant, and hesitation is deadly.

There are captured-soldier accounts—again, varying in detail—that describe the Australians not as normal soldiers but as something uncanny: men who didn’t move like the Americans, who didn’t leave trash, who didn’t speak, who didn’t make camp the way other units did. Men who could appear near a trail, change something, and vanish. Men whose presence was felt only after the fact, when what you believed was “your” suddenly turned into death.

The Americans were loud and heavy, those accounts say. You could hear them. You could ambush them or avoid them. But the Australians…

You didn’t know they were there until the jungle proved it.

That reputation wasn’t built on myth alone. It was built on a philosophy of fieldcraft: treat everything as a message, treat every message as potentially false, and trust your senses more than your assumptions.

This wasn’t heroism in the cinematic sense.

It was craft.

And craft is what special units live on.

Meanwhile, conventional forces lived in a different reality. Large formations meant noise: boots, gear, packaging, radios, the constant friction of moving a body of men through thick vegetation. Even if you tried to be quiet, the sheer mass of it created sound. And sound in the jungle travels strangely. It bounces. It magnifies. It becomes a warning.

That’s why booby traps weren’t just physically lethal for conventional forces—they were psychologically corrosive. They made men hesitate, because every step could be a punishment. They made whole platoons move like they were walking on glass.

And the enemy understood something simple:

You don’t have to kill every man.

You just have to make every man afraid to move.

Fear makes you predictable.

Fear makes you slow.

Fear makes you stay on trails when you shouldn’t.

Fear makes you watch the wrong places.

And in Vietnam, the enemy’s engineering of fear was often more effective than direct firefights.

The SAS response—their refusal to be heavy, loud, and predictable—was part of why their patrols could operate with such effectiveness for so long. Their “success” wasn’t measured by territory captured. It was measured by intelligence gathered, targets identified, contact survived, and most importantly: the ability to leave without being detected.

When you think about it, that’s the truest victory in jungle reconnaissance:

To be present… and leave no proof you ever existed.

That’s why the point man’s role becomes almost sacred. He isn’t just leading a team. He’s reading for them. He’s the interpreter between the jungle’s lies and the patrol’s survival.

He doesn’t just prevent a casualty.

He prevents a chain reaction. One man hurt becomes a rescue operation. Rescue becomes noise. Noise becomes contact. Contact becomes an extraction under fire.

In the jungle, one mistake doesn’t just injure one body.

It can compromise an entire mission.

So the SAS point man’s attention—his refusal to assume—becomes as lethal as any weapon.

And when that attention is paired with imagination—when the patrol decides not only to avoid danger but to manipulate it—the environment itself becomes a chessboard.

The enemy lays a piece.

The SAS moves it.

The enemy returns and finds the board has changed.

That is the essence of unconventional warfare: you don’t always win by hitting harder. Sometimes you win by making the enemy question his own certainty.

But none of this is clean.

None of it is romantic.

There is a temptation in military storytelling to turn these things into myth—“phantoms,” “ghosts,” “supernatural silence.” The truth is less magical and more brutal:

These were humans who trained their nerves until fear didn’t control their fingers.

These were humans who accepted discomfort as strategy.

These were humans who paid for invisibility with discipline.

And discipline has a cost.

The cost is hunger. Sleep deprivation. Constant tension. The kind of mental fatigue that doesn’t show on the body but wears grooves into a person’s mind. The cost is moving through a world where the ground can lie and your survival depends on catching the lie before you step into it.

That isn’t glamorous.

It’s grinding.

It’s living in a permanent state of controlled alertness.

And yet, that state is what allowed them to do what conventional forces often couldn’t: move deep, stay long, leave clean.

In broad strokes, Vietnam is often painted with loud images: napalm runs, artillery, helicopters slicing the sky, explosions so large they become their own weather.

But the real war—especially in the jungle—was often fought in quiet spaces.

A wire.

A leaf.

A footprint.

A trap discovered and neutralized without a sound.

A trap altered and left behind as a silent message: You don’t own this ground.

And perhaps that’s the most unsettling lesson of it all.

In a jungle war, the enemy doesn’t have to be a man with a rifle.

The enemy can be a clever mind that turns your assumptions against you.

The enemy can be the ground itself—weaponized by someone who understands that fear is heavier than any pack.

The Australians understood that. They weren’t “better” because they were braver in some mythical way. They were better because they treated warfare as a thinking person’s game. They refused to be dragged into the enemy’s preferred contest of paranoia and weight.

Instead, they rewrote the contest.

They made the enemy fear his own certainty.

They made “safe” feel dangerous.

They made the jungle—once the enemy’s ally—feel like a place where even the ground could betray.

And that is a kind of victory that doesn’t show on maps.

It shows in the way men walk—slower, suspicious, burdened not by supplies but by doubt.

The phrase stamped on the face of a weapon—front toward enemy—is simple. It’s an instruction. A reminder.

But in Vietnam, “front” and “enemy” were never stable categories.

The enemy was often the thing you didn’t see.

And sometimes, the most dangerous weapon in the jungle wasn’t what the enemy carried.

It was what you carried… and failed to respect.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.