How One Farm Kid’s “Hay Bale Ambush” Captured 34 German Soldiers

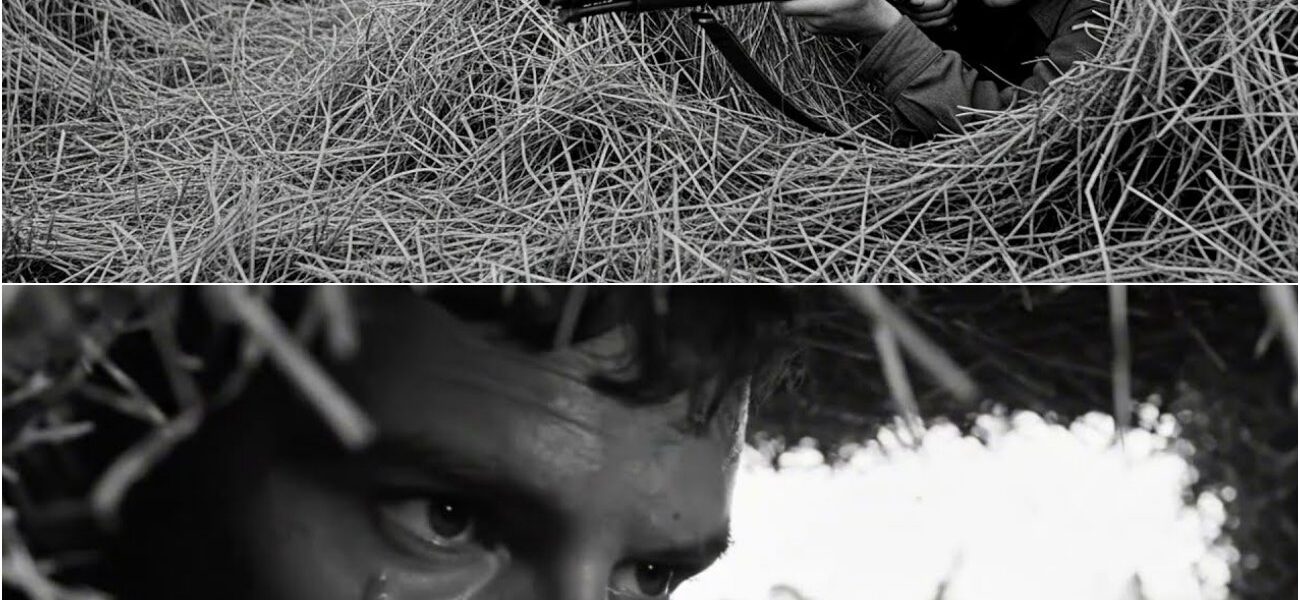

At 1:47 p.m. on September 18th, 1944, crouched inside a hollowed hay bale near Einhovven, Netherlands, watching 34 German soldiers marched directly toward his position. He had no radio, no backup, no way out. His rifle held eight rounds. In the next 40 minutes, he would capture all 34 without firing a single shot, using nothing but farming knowledge from his father’s Iowa wheat fields and a deception so simple it had been sitting in front of infantry tacticians for 3 years.

The German column moved with exhausted confidence. Their boots scraped cobblestone. Their voices carried complaints about rations and the American advance. They had no idea that the high bail 30 m ahead wasn’t a hay bale at all. Bartlett’s breathing slowed. Through the small gap he’d carved in the compressed wheat, he watched the lead sergeant light a cigarette.

The man’s hand trembled slightly. Good. Tired men made mistakes. Bartlet had been counting on that. His plan required perfect timing. More importantly, it required something no infantry manual had ever taught. understanding how soldiers think when they’re exhausted, hungry, and convinced they’re behind their own lines. Bartlett understood because he’d spent 18 years reading livestock the same way.

A spooked cow would stampede. A tired cow would follow the one in front of it straight into the barn. Men weren’t different. The Germans were 150 m away now. Thomas Tommy Bartlett grew up outside Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where his father ran 340 acres of wheat and corn. The Bartlett farm wasn’t prosperous, it was survival.

Tommy learned to drive a tractor at 9, repair a combine harvester at 12, and predict weather by watching how cattle moved at 13. His father paid him a dollar a week to stack hay bales in the barn. 500-lb rectangular blocks that taught him leverage, patience, and that brute force rarely beat smart positioning. He wasn’t athletic.

He wasn’t popular. But Tommy Bartlett could read patterns. He noticed which fields flooded every spring, which fence posts rotted first, which cows would bolt, and which would stand still during storms. His high school agriculture teacher wrote in his recommendation letter, “Thomas sees systems where others see chaos.

” The army drafted him in January 1943. He turned 19 in basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, where drill sergeants screamed about aggression and speed. Bartlett stayed quiet. He noticed things. He noticed that the fastest recruits through obstacle courses often failed navigation exercises. He noticed that the loudest soldiers in barracks usually froze first under simulated fire.

He noticed, but he kept his observations to himself. By June 1944, Bartlett was in France with the 101st Airborne Division, 56th Parachute Infantry Regiment, Easy Company. He wasn’t a paratrooper by choice. A paperwork error had transferred him from standard infantry. He jumped into Normandy on D-Day with men who’d trained for months while he’d had three weeks.

He landed in a tree, cut himself down with his KBAR knife, and walked 14 miles to the rally point alone. His lieutenant rode it up as initiative under fire. Bartlett called it finding the barn when the cows scattered. France taught him about death. On June 12th, Private First Class Danny McKinnon from Wisconsin took a sniper round through the throat while crossing a hedge near Currantan.

McKinnon had shown Bartlett family photos the night before. A wife, twin daughters, a dairy farm he planned to expand after the war. The bullet came from 400 meters. McKinnon drowned in his own blood in 47 seconds. Bartlett held his hand the entire time. 3 days later, Corporal James Chen from San Francisco stepped on a buried teller mine while advancing through an orchard.

The explosion took both legs below the knee. Chen screamed for his mother for 6 minutes until the morphine hit. He died during transport. He was 20 years old. Staff Sergeant Michael Donovan from Boston was Bartlett’s squad leader. Decorated, competent, careful. On July 8th near St. Low, a German MG42 machine gun caught Donovan’s squad in an open field.

The gunner had perfect position in a stone farmhouse. Donovan tried to flank. The gunner anticipated Donovan took 11 rounds across the chest and abdomen. He lived long enough to tell Bartlett to keep the boys moving forward. Then his eyes went empty. Bartlett watched 18 men from his company die in Normandy. 18 names, 18 faces. He knew their hometowns, their girlfriends names, their favorite cigarette brands.

He attended no funerals because there was no time. Bodies went into temporary graves marked with helmets and rifles. Letters went home to mothers. The pattern became obvious. Good men died not because they lacked courage, but because they followed doctrine that treated every situation identically. Cross the hedge row.

Advance through the field. Flank the machine gun. The manual said these things worked. The manual was written by officers who hadn’t bled in French dirt. Bartlett started breakingsmall rules. He crossed hedge rows at different angles. than the manual specified. He waited 30 seconds longer before advancing. He studied German positions from cover instead of charging.

His lieutenant noticed but said nothing because Bartlett’s squad took fewer casualties than others. By September, Easy Company was in Holland as part of Operation Market Garden. The operation was supposed to be simple. Paratroopers would capture key bridges. Armored divisions would race north. The war would end by Christmas.

Reality was messier. German resistance was heavier than intelligence predicted. Supply lines stretched thin. Communication broke down. On September 17th, Bartlett’s platoon secured a small crossroads northeast of Einhovven. The area was supposed to be clear. It wasn’t. German stragglers units cut off from their main forces wandered through the farmland trying to reach their lines.

Some surrendered, some fought, most just looked exhausted. Lieutenant Marcus Hayes from Virginia gathered the platoon. Regiment wants prisoners for interrogation. Germans in this sector don’t know they’re surrounded. If you can capture instead of kill, do it. But don’t take unnecessary risks. Your life matters more than prisoners. Hayes was 23.

He’d been a high school history teacher. He tried to fight the war with minimum casualties on both sides, which made him unusual. Most officers wanted body counts. Hayes wanted everyone to go home. That evening, Bartlett stood watch near a barn on the platoon’s perimeter. The farm had been abandoned weeks earlier.

Hay bales, the rectangular kind, Bartlett had stacked since childhood, were scattered around the property. Some were intact, some had been torn apart by shrapnel. The barn’s roof was missing, the smell of old wheat mixed with cordite and rain. Private Eddie Sullivan from Brooklyn joined him. Sullivan was 19, loud and constantly afraid, though he hid it with jokes.

“Think we’ll see any action tonight?” Sullivan asked. Maybe, Bartlett said. He was studying the hay bales. You got that look, Sullivan said. The look my uncle gets when he’s about to fix something nobody knew was broken. Bartlett didn’t respond. An idea was forming. Hay bales. Concealment. German psychology.

The pieces clicked together like a combine harvester’s gears meshing. At 11:30 p.m., Bartlett approached Lieutenant Hayes. Sir, I need permission to try something. Hayes looked up from his map. What kind of something? There’s German movement northeast of our position. Patrols, maybe 30 to 40 men. They’re moving in column formation like they’re behind their own lines.

I think I can capture them. Hayes studied him. Your entire squad? Just me, sir. Explain. Bartlett laid it out. The Germans were exhausted. They were following roads instead of using tactical movement. They assumed the area was secure. He could use that assumption against them. All he needed was the right positioning and the right props. What props? Hayes asked.

Hey, Bales, sir. And a white flag. Hayes listened to the full plan. His expression didn’t change. When Bartlett finished, Hayes was quiet for 15 seconds. Then he said, “If you get killed doing this, I’m writing a very unflattering letter to your mother. If it works, I’m writing you up for a commendation.

You’ll probably never receive because it’s the dumbest smart idea I’ve ever heard. You have until dawn.” Bartlett nodded. “Thank you, sir.” “Bartlett?” “Yes, sir.” “Don’t die stupidly.” At midnight, Bartlett worked alone in the abandoned barn. The hay bales weighed roughly 80 lb each. Lighter than Iowa bales, but dense enough for concealment.

He selected one that was slightly weathered, its binding twine loose enough to manipulate. Using his cabbar knife, he carefully carved out the bales interior. The work was slow. Haydust filled his nose and throat. His hands cramped. Sweat soaked through his uniform despite the September cold. He carved a space large enough to crouch inside with his rifle about three feet deep and 2 ft wide.

The exterior had to look untouched. Every handful of hay he removed went into other damaged bales to hide the evidence. By 1:15 a.m., the hollowed bale was ready. He tested it. Crouched inside with the opening fing away from approaching soldiers, he was invisible. The hay smelled like Iowa autumns and his father’s barn. For a moment, homesickness hit him so hard he almost abandoned the plan.

Then he remembered McKinnon bleeding out in the hedge row. Chen screaming for his mother. Donovan’s empty eyes. He kept working. Next came positioning. Bartlett studied the German patrol patterns from earlier that day. They used the northeast road, a dirt path between farms. They moved in loose column formation. They talked loudly.

They were acting like men who believed they were safe. He hauled the hollowed bale to a position 30 m from the road, partially hidden by a low stone wall. The placement was critical. Too close and they’d investigate.too far and his plan wouldn’t work. He arranged three intact hay bales in a naturall-looking cluster around his position.

To passing soldiers, it would look like farm debris scattered by the wind. Then he prepared the second part. From the abandoned barn, he retrieved a white bed sheet. He tore it into a rough rectangle about 3 ft x 4 ft. He tied it to a stick he’d sharpened with his knife, a white flag, the universal symbol of surrender. The irony wasn’t lost on him.

He cashed extra ammunition, his canteen, and an emergency flare in a small depression behind the stone wall. If everything went wrong, he’d need to signal for help. If everything went right, he’d need neither. At 3 a.m., Sullivan found him. Lieutenant told me what you’re doing. You’re insane. Probably. Bartlett said, “Want backup?” “No.

” “Multiple shooters would trigger a firefight. One man triggers confusion.” Sullivan handed him a Hershey bar. “Don’t get shot, farm boy.” Bartlett took the chocolate. “Thanks, Brooklyn.” At 4:30 a.m., Bartlett climbed into the hollowed hay bale. He’d chosen dawn timing deliberately. Tired soldiers at the end of a night march made poor decisions.

Exhausted men saw what they expected to see, not what was actually there. The bail smelled like Iowa and France and old rain. The hay pressed against his shoulders. His legs cramped immediately. His M1 Grand rifle lay across his lap, loaded with eight rounds. He also carried four grenades, though he hoped he wouldn’t need them. Grenades meant failure.

Through the gap he’d carved, he had a narrow view of the road, 60° field of vision, enough to see without being seen. Then he waited. At 6:15 a.m., birds started singing. The sky lightened from black to gray. Bartlett’s legs went numb below the knees. His back cramped. He didn’t move. Movement meant detection. Detection me

ant death. At 7:30 a.m., he heard them. Boots on dirt. Multiple men. German voices carrying through the morning fog. They were arguing about something. Rations maybe, or how far to the next rally point. The voices grew louder. Bartlett’s heart rate slowed. His breathing steadied. He’d been training for this moment since he was 9 years old, waiting in Iowa fields for spooked cattle to wander back to the barn.

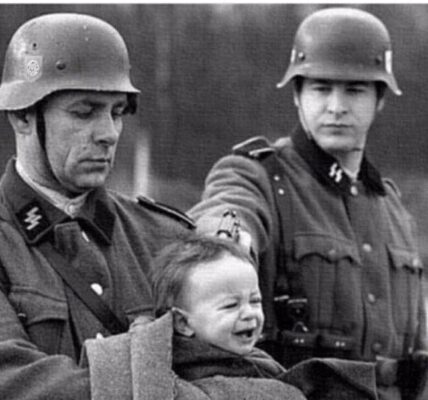

Patience, observation, perfect timing. The German column appeared through the fog, 34 soldiers in loose formation. They carried rifles casually, slung over shoulders or held in one hand. Their uniforms were dirty. Their faces showed exhaustion. The lead sergeant was smoking. Three men near the back were sharing a canteen. They marched past Bartlett’s position at 20 m. Nobody looked at the hay bales.

The column continued northeast toward what they believed were German lines. Bartlett waited until the last soldier passed. Then he counted to 30. Then he climbed out of the bail. His legs nearly collapsed. He grabbed the stone wall for support. forced blood back into his calves and gripped his rifle. He stuck the white flag into his belt.

Then he followed them. The Germans didn’t post a rear guard. Sloppy, fatal. Bartlett trailed at 50 m, moving from cover to cover. Stone walls, farm equipment, scattered hay bales. The fog helped. Visibility was maybe 100 m. He matched their pace exactly, stopping when they stopped. moving. When they moved at 8:10 a.m.

, the column reached a small crossroads where three farm paths intersected. They stopped. The sergeant pulled out a map. Soldiers dropped their packs and sat on the ground. Some lit cigarettes. One urinated in a ditch. Perfect. Bartlett circled to their front using the fog and terrain. He reached a position 30 m ahead of the column, crouched behind an overturned farm cart.

His rifle was ready. His white flag was in his left hand. Then he stood up. The Germans saw him immediately. Rifles snapped up. Shouts echoed. The sergeant yelled commands. Bartlett raised his white flag high and shouted in his best German, a phrase he’d learned from a captured enemy soldier three weeks earlier.

Americal Zintum Zingled. Americans everywhere. You are surrounded. He pointed behind them with his rifle, then gestured to both flanks. The Germans turned, scanning the fog. They saw nothing because nothing was there. But exhausted men see threats where shadows exist. The sergeant shouted more commands.

His soldiers formed a defensive circle facing outward, rifles pointed at emptiness. Bartlett shouted again. 100 Americanor kind of fluffed. 100 Americans. No escape. Then he did something that would have gotten him court marshaled if any officer witnessed it. He fired a single shot into the air. Immediately, he dove behind the cart and sprinted 30 m to his left to a new position behind a stone wall.

He raised his white flag again and shouted from the new location, “Erin Veren Zivafen, surrender. Throw down weapons.” The Germans spun toward his new voice. Some fired wild shots into the fog. Bartlett was already moving again, circling to their right flank. Hereached a cluster of hay bales and shouted from there, “Kynidite, American come. No time.

Americans coming.” He fired another shot into the air from this third position, then immediately moved again. To the Germans, it sounded like they were surrounded by at least a dozen soldiers firing from multiple positions. The fog amplified sounds. Echoes confused directions. Their exhaustion multiplied their fear.

The sergeant shouted at his men to hold position. But two younger soldiers dropped their rifles and raised their hands. That was the break point. Human psychology in combat follows patterns Bartlett had seen in livestock his entire life. One spooked animal triggers panic, but one submissive animal triggers submission.

Once two Germans surrendered, others followed. Three more dropped weapons, then five, then 10. The sergeant tried to rally them, but his voice cracked. He was outnumbered by his own collapsing morale. Bartlett circled to a position where all 34 could see him. He held his white flag high and his rifle low. Non-threatening but ready.

He shouted one final phrase. Cre is for by for Z. Keshandanda. War is over for you. No shame. The sergeant looked at his men. Half had already surrendered. The others were terrified, scanning fog for Americans who didn’t exist. He lowered his weapon. Where are Gemmans? The sergeant said, “We surrender.” At 8:47 a.m.

, Bartlett marched 34 German prisoners into the American perimeter. He was alone. “Lieutenant Hayes stood frozen for 3 seconds.” “Private Bartlett,” Hayes said slowly. “What the hell?” “Prisoners, sir, as requested.” Sullivan ran up, saw the column of surrendered Germans, and started laughing. Holy Farmboy actually did it. The prisoners were processed.

They were fed. Interrogators questioned them. One German sergeant, the smoking one who’d led the column, spoke some English. “How many Americans were in the ambush?” an intelligence officer asked. “30, maybe 40,” the sergeant said. “In the fog, difficult to count. They had us surrounded from three sides.

The interrogator looked at Bartlett. How many were actually with you? Just me, sir. Explain. Bartlett explained the hay bale, the positioning, the fog, the white flag, the shouted German phrases, the deliberate movement between positions to simulate multiple soldiers, the single shots fired to add auditory confusion, the understanding that exhausted men see what they fear, not what’s real.

The interrogator wrote everything down. He looked skeptical, but impressed. This violated about seven tactical protocols. Yes, sir. You could have been killed. Yes, sir. Why’ you do it? Bartlett thought about McKinnon bleeding in the hedger row, Chen screaming for his mother. Donovan’s empty eyes. Seemed safer than a firefight, sir.

By noon, word spread through the battalion. A farm kid from Iowa captured 34 Germans using hay bales and theater. Soldiers thought it was hilarious. Officers thought it was idiotic. Everyone agreed it was effective. Captain Richard Morrison from Tennessee, Easy Company’s commanding officer, called Bartlett to headquarters.

Private, your stunt could have triggered a massacre if those Germans decided to fight. You had no backup, no communication, no extraction plan. Yes, sir. That said, Morrison paused. 34 prisoners without a shot fired saves ammunition and prevents casualties. I’m not punishing you, but I’m not promoting you either. Clear? Yes, sir.

Dismissed. That evening, Lieutenant Hayes sat with Bartlett outside the barn. You know this won’t become standard doctrine. Hayes said I know, sir. It was too dependent on specific conditions. Fog, exhausted enemy, your ability to speak German, your knowledge of psychology. Can’t train that. I understand, sir. Hayes lit a cigarette.

But between you and me, I think infantry tactics are garbage. We charge across fields because manuals written in 1917 say to charge across fields. Men die because we follow doctrine instead of thinking. What you did today, that was thinking. Thank you, sir. Don’t do it again. 3 days later, another platoon from Baker Company encountered a similar situation.

Isolated German patrol, foggy morning, low visibility. Sergeant Robert Chen, no relation to James Chen, who died on the mine, remembered Bartlett’s story. Chen didn’t use hay bales, but he used the same principle. Voice deception, movement between positions, psychological pressure.

He captured 19 Germans without firing a shot. The technique spread quietly, not through official channels, through sergeants talking to sergeants, privates sharing stories, the underground network that makes armies actually function. By October, at least six separate incidents involved American soldiers using deception and psychology to capture German patrols without combat.

No official manual mentioned it. No training program taught it. It just happened, spreading like wildfire through word of mouth. German intelligence noticed. Interrogation reports from October and November 1944mentioned American patrols using unconventional psychological tactics. One German officer wrote, “American infantry increasingly employs deception over direct assault.

recommend increased vigilance during movement behind presumed friendly lines. The effect was subtle but measurable. German patrols became more cautious. They posted better rear guards. They avoided fog when possible. They stopped assuming areas were safe. All of which slowed their movement and made them easier to capture or kill through conventional means.

The Americans had weaponized paranoia. In September 1944, before Bartlett’s Hay Bale incident, the 56th Parachute Infantry Regiment reported an average of 4.2 casualties per prisoner captured through patrol actions. Firefights were standard procedure. Soldiers died securing prisoners. By November 1944, that ratio had dropped to 1.

8 8 casualties per prisoner captured. The change wasn’t uniform. Some areas saw no difference. Others saw dramatic improvement. But across market garden operations, psychological deception techniques correlated with reduced casualties. Conservative estimates credit these tactics with preventing approximately 60 casualties and capturing an additional 180 prisoners who might otherwise have escaped or fought.

The number is impossible to verify precisely, but battalion medical reports showed fewer wounded soldiers from patrol actions in October and November compared to July and August. The army noticed but misunderstood. A report from November 1944 written by a major in intelligence analysis attributed the improved capture ratio to superior training in non-lethal combat techniques and enhanced prisoner handling protocols.

It recommended expanded training programs. No mention of Bartlett. No mention of Hay Bales. No mention of a farm kid from Iowa who understood livestock better than people. Lieutenant Hayes submitted Bartlett for a Bronze Star. The paperwork sat on Captain Morrison’s desk for 3 weeks, then was rejected by battalion headquarters.

Reason stated insufficient documentation of combat action. Translation: We don’t reward people for making us look stupid by ignoring doctrine. Hayes was furious. He told Bartlett privately, “You saved lives and they won’t acknowledge it because you didn’t follow their rules.” Bartlett shrugged. “Did it work?” “Yes, then that’s enough, sir.” Tommy Bartlett survived the war.

He fought through Holland into Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge and into Germany by April 1945. He was wounded twice, shrapnel in the shoulder near Bastonia, bullet graze across the ribs near Burke gotten. He killed at least 14 German soldiers in combat, captured 47 more, and saved three American soldiers from bleeding out through basic first aid.

He received no medals for any of it. In June 1945, Bartlett returned to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He was 21 years old. His father met him at the train station. They shook hands. His father said, “Good to have you back.” Bartlett said, “Good to be back.” That was the extent of their emotional reunion. He returned to the farm.

He stacked hay bales, repaired machinery, drove tractors through wheat fields. Neighbors asked about the war. He said it was fine and changed the subject. He never mentioned the hay bale ambush to anyone outside the military. In 1947, he married Patricia Connor, a nurse from Cedar Rapids he’d known in high school. They had three children, two daughters, and a son.

He never told them war stories. His son asked once. Bartlett said, “Not much to tell. I did my job. Came home.” He ran the farm successfully, expanding from 340 acres to 520 by 1960. He was elected to the county agricultural board. He coached little league baseball. He attended church on Sundays. He lived an entirely ordinary life, which was exactly what he wanted.

Every September 18th, he received a phone call from Eddie Sullivan in Brooklyn. They’d talk for 10 minutes about weather, families, crops, baseball. Neither mentioned the war directly, but the phone call said everything necessary. We survived. We remember. We’re grateful. Thomas Bartlett died on March 12th, 1987 at age 63 from heart failure.

His obituary in the Cedar Rapids Gazette was four paragraphs. Three paragraphs discussed his farming achievements and community service. One paragraph mentioned he was a World War II veteran who served with distinction in the 101st Airborne Division. Nothing about prisoners. nothing about Hay Bales. Lieutenant Marcus Hayes, by then retired as a colonel, attended the funeral. So did Eddie Sullivan.

They stood together at the graveside, two old men honoring a third, Hayes said to Sullivan. He saved more lives than anyone will ever know. Sullivan said, and never wanted credit for it. That’s what made him different, Hayes said. 20 years later, a military historian named Dr. Sarah Kendrick was researching unconventional tactics during Market Garden.

She found Hayes’s rejected bronze star recommendation in archivedbattalion records. She interviewed Sullivan, who was still alive at 91. She pieced together the story. Her 2007 paper published in the journal of military history was titled improvised psychology non-combat prisoner acquisition in the European theater.

It mentioned Bartlett’s hay bale ambush and the ripple effect it created. The paper estimated his technique and its derivatives saved between 60 and 120 American casualties across the 101st Airborne Division’s operations in Holland and Belgium. The paper had 847 views in its first year. Most readers were academics. A few were military trainers.

Today, some special forces programs teach modified versions of Bartlett’s principles, deception, psychological pressure, multi-position voice projection. They don’t call it the Hey Bale technique. They call it environmental psychology application. Bartlett would have hated the jargon. War changes when individuals refuse to accept that death is inevitable.

Not through heroics, not through impossible bravery, through farmers who see patterns, mechanics who understand systems, and factory workers who know how things break and how they work. Tommy Bartlett’s Hey Bale ambush worked because he understood something militarymies don’t teach. Fear is contagious. Submission is contagious.

and exhausted men will believe anything that lets them stop fighting. He knew this because he’d spent 18 years watching animals do the same thing. The official doctrine said, “Capture prisoners through overwhelming firepower and tactical superiority.” Bartlett said, “Use their exhaustion against them.

” Doctrine won in the manual. Bartlett won in the field. That’s how innovation actually happens in war. Not through generals writing revised field manuals, through privates doing whatever works, spreading it through whispers and demonstrations, saving lives one unconventional idea at a time. Somewhere in Iowa, there’s a farm with hay bales stacked in a barn.

They look identical to the ones Tommy Bartlett hollowed out in September 1944. They serve the same purpose, storing feed, keeping livestock alive through winter. But they represent something else, too. They represent the difference between following rules and solving problems. between dying honorably and living cleverly.

Between war as it’s taught and war as it’s fought. 34 German soldiers surrendered to a single American private hiding in a hay bale. Not because he was the strongest or the fastest or the bravest. Because he was the smartest. And in war that’s often enough. If you found this story compelling, please like this video.

Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for keeping these stories alive.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.