Engineers Called a 1,000-Pound Cannon “Pilot Suicide” — Until It Stopped a 2,000-Ton Warship. NU

Engineers Called a 1,000-Pound Cannon “Pilot Suicide” — Until It Stopped a 2,000-Ton Warship

At 9:17 a.m. on a humid morning in early 1942, a twin engine bomber hurtled just 50 feet above the Pacific. Salt spray slapped its aluminum skin. The engine screamed. Inside the cockpit, nobody spoke. Not because there was nothing to say, because everything that mattered had already been decided.

Ahead of the aircraft, a Japanese destroyer cut through the water at over 30 knots. 2,000 tons of steel, 5-in guns, dozens of anti-aircraft barrels already turning upward. From the bridge of that ship, the American bomber looked like a mistake. Too low, too slow, too close. And yet, it kept coming. Inside the nose of that airplane, was something that should not have existed.

a field cannon, a 75 mm artillery gun, the same weapon used to smash concrete bunkers and light tanks, weighing nearly 1,000 lb, bolted inside a bomber never designed to fire forward artillery. Every engineer involved had used the same phrase, pilot suicide. They were not being dramatic. They were doing math.

The recoil force of that gun was measured in tons. On the ground, it buried spades into dirt. In a tank, it relied on 30 tons of steel to absorb the shock. In an aircraft, there was only thin aluminum rivets and lift. Fire it, the reports warned, and the nose would tear off. The aircraft would stall. The pilot could black out.

The wings might fold. That was not theory. That was calculation. I want to pause here for half a second because this is the moment most people miss. The danger was not the enemy. The danger was the trigger. Now, imagine being the man with his hand on it. The bomber did not climb. It did not turn away.

It did not open Bombay doors like Doctrine demanded. Instead, it dropped lower. The pilot aimed the entire aircraft straight at the destroyer’s bow. Not alongside, not from above, headon, closing speed approaching 400 mph. On the ship below, Japanese gunners opened fire. Traces ripped upward. Black flack bursts cracked the air.

At this range, one direct hit from a 5-in shell would have erased the aircraft instantly. No parachutes, no survivors. Still, the bomber held its line. Inside the cockpit, the pilot did not have a bomb site, no computer, no radar, just a fixed ring sight bolted to the dashboard and his own nerve. To aim the gun, he had to aim the plane.

There was no correction after the shot, no second chance built into the physics. I find this hard to overstate. This was not bravery in the abstract. This was a man flying straight into gunfire, trusting that someone else’s forbidden idea might work. At roughly 800 yd, the machine guns fired first. Heavy 50 caliber rounds poured forward at nearly 50 rounds per second.

They were not meant to sink the ship. They were meant to blind it. Glass shattered on the bridge. Exposed gunners ducked. For a brief, fragile moment, the wall of fire weakened. That moment was everything. The destroyer filled the windshield. steel plates, rivets, spray exploding along the bow. The pilot made a micro adjustment, lifting the nose just enough to aim at the water line beneath the forward turret where boilers lived.

Where one hit could change everything. The man loading the cannon tapped the pilot’s shoulder. The shell was in. 15 lb of high explosive. The breach was closed. The aircraft was steady, barely. The pilot squeezed the trigger. For an instant, it felt as if the bomber stopped in midair. not slowed, stopped. The recoil slammed through the fuselage like a collision.

The cockpit filled with white smoke and cordite. The airframe shuddered from nose to tail. Every rivet was tested. This is the point where the engineers expected the wings to come off. They didn’t. The shell left the barrel at roughly 2,000 ft pers. It crossed the open water in less than 1 second. It struck the destroyer just above the water line, punched through steel plating past a bulkhead, and detonated inside the ship.

Not outside, inside. On the bridge, Japanese officers felt the ship lurch violently. Steam erupted. Power failed. The wake behind the destroyer began to fade. A predator that had ruled the ocean for years was suddenly wounded by something it was never meant to fight. The bomber roared overhead so close that crewman could see chaos on the deck below. I always come back to this image.

Aluminum passing over steel. One moment separating theory from reality. Cuz seconds earlier, this aircraft was supposed to be dead. Instead, the destroyer was. The pilot pulled away hands, shaking engines, still running wings still attached. Behind him, smoke poured from the stricken ship. The impossible had just happened, and nobody involved would ever look at air warfare the same way again.

And here is the uncomfortable truth. Every expert had been right on paper, and every one of them had been wrong in war. At 8:30 a.m., 20,000 ft above the Solomon Sea, the theory looked perfect. The formation was tight. The air was calm. Bombay doors opened on schedule. Below them, the Japanese convoy moved like clockworkdestroyers, slicing water at just over 30 knots white, wakes clean and confident.

According to doctrine, this was the future of warfare. Precision bombing, science, certainty. The bombs fell. It took roughly 45 seconds for a 500lb bomb dropped from 20,000 ft to reach sea level. 45 seconds does not sound like much on paper. In reality, it is an eternity. In that time, a destroyer moving at 30 knots can travel more than half a mile.

Enough distance to make the most accurate calculation meaningless. The bombs hit the ocean, not the ships. White columns of water erupted hundreds of yards away. The destroyers did not scatter. They did not panic. Their captain simply ordered small course corrections. Left, right, minor turns. The bomb splashed harmlessly into empty sea.

This happened again and again and again. The Americans had spent millions of dollars perfecting the Nordon bomb site. It was advertised as capable of dropping a bomb into a pickle barrel from 4 m up. That claim was not entirely false. against stationary targets, factories, rail yards, cities. It worked. Against a warship that could see the bomber coming nearly a minute before impact, it was almost useless.

I want to be very clear here because this matters. The pilots were not failing. The system was. Every bombing run followed the manual. Stable approach, level flight, calculated release, and every run produced the same result. Misses measured not in feet, but in football fields. From the bridge of Japanese ships, American bombs became a kind of dark joke.

Watch the bay doors open, start the stopwatch, turn the wheel, survive. By early 1942, this failure was not theoretical. It was strategic. The Japanese Navy used fast destroyers to run what Allied pilots bitterly nicknamed the Tokyo Express. Night after night, ships delivered thousands of troops, vehicles, ammunition, and food to island garrisons across New Guinea and the Solomons.

These supplies kept Japanese forces alive, and American air power could not stop them. High altitude bombers flew back to base with empty bomb racks and nothing to show for it. Crews were exhausted. Maintenance teams were scavenging parts just to keep aircraft in the air. Morale was collapsing alongside the math.

This is where most histories soften the story. They talk about adaptation learning curves, gradual improvement. That is not what it felt like at the time. It felt humiliating. A destroyer captain could look up, see a bomber formation at altitude, and feel safe. That should never have been true. Yet, it was, and everyone involved knew it.

The problem was physics, not courage. A bomb is a dumb object once released. It cannot think. It cannot adjust. A ship can. And water gives ships freedom that land targets do not have. No roads, no rails, no fixed position, just open space and speed. Someone had to admit that the future everyone believed in was failing in the present.

That someone was General George Kenny. When Kenny arrived in the Southwest Pacific, he did not bring new manuals. He brought skepticism. He looked at the reports, the missed distances, the timing charts, and he threw them away. Not because he rejected science, but because he understood reality. Trying to hit a moving destroyer from 20,000 ft, Kenny later said, was like standing on top of a skyscraper and trying to drop a marble into a coffee cup being dragged by a sprinting cat.

The meta stuck because it was painfully accurate. I agree with him more than I’m comfortable admitting because once you see it, you cannot unsee it. The longer the bomb falls, the more time the enemy has. Time to maneuver, time to react, time to survive. High altitude bombing handed the initiative to the target. That was the unforgivable flaw.

Kenny did not ask how to improve bombing accuracy. He asked a different question. How do you remove time from the equation? The answer was obvious and insane. You get closer. Closer means lower. Lower means danger. Low altitude puts aircraft inside the envelope of every anti-aircraft gun on the ship. It removes the safety of distance.

It trades calculation for nerve, but it also collapses the timeline. At 50 ft above the water, there is no 45-second delay. There is no graceful arc. There is impact almost immediately. The manual said this was suicidal. The numbers said losses would be catastrophic. And maybe they were right. But the alternative was losing the campaign slowly, ship by ship, island by island.

That is the moment where doctrine stopped being useful and necessity took over. Kenny did not yet know what the weapon would be. He only knew what it could not be. It could not be another bomb dropped from the stratosphere. It had to hit now. It had to hit hard. And it had to deny the enemy time to think. In war, that realization is often more important than any invention.

And once you accept it, there is no going back. The idea did not arrive gently. It arrived like a bad smell in a closed room. Someonesomewhere on a hot Pacific airfield looked at the problem long enough and stopped asking how to drop bombs better. They asked a more dangerous question. What if the airplane did not drop anything at all? What if it fired, not rockets, not machine guns? Those already existed and everyone knew their limits.

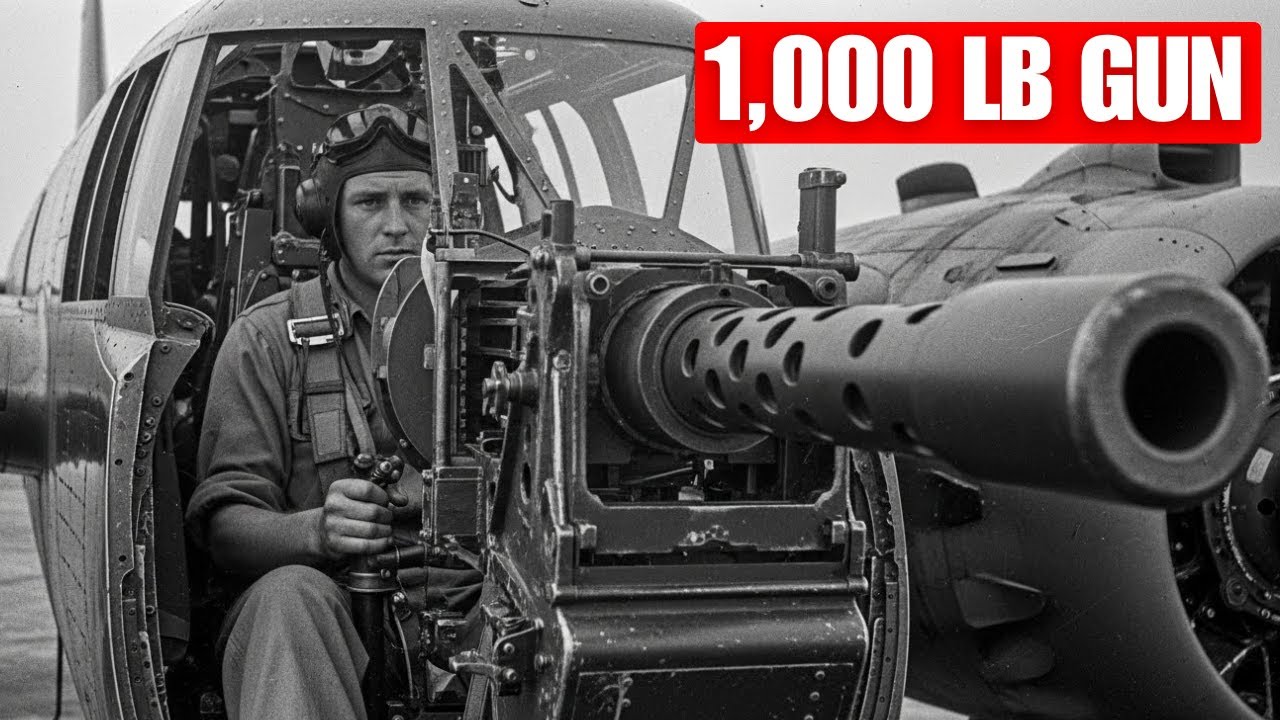

Machine gun rounds bounced off ship hulls. They made noise. They made sparks. They rarely made ships stop. To a destroyer, you had to reach inside it. Boilers, turbines, steering gear. You needed artillery. The weapon that fit that requirement already existed. The army’s 75 mm M4 field cannon.

A gun designed to punch through concrete and armor. A gun that fired a 15lb shell with enough force to tear through halfin steel. On the ground, it weighed nearly 1,000 lb with recoil systems and mounting hardware even more. It had never been designed to fly. The moment the proposal reached engineering desks in the United States, the response was immediate and unanimous. No.

Not cautious. No, not hesitant. No, absolute no. Stress calculation showed catastrophic failure. The recoil impulse alone exceeded what the forward fuselage of a medium bomber could absorb. Fire the gun, the engineers warned, and the aircraft would decelerate violently. Lift would collapse. The nose would fail.

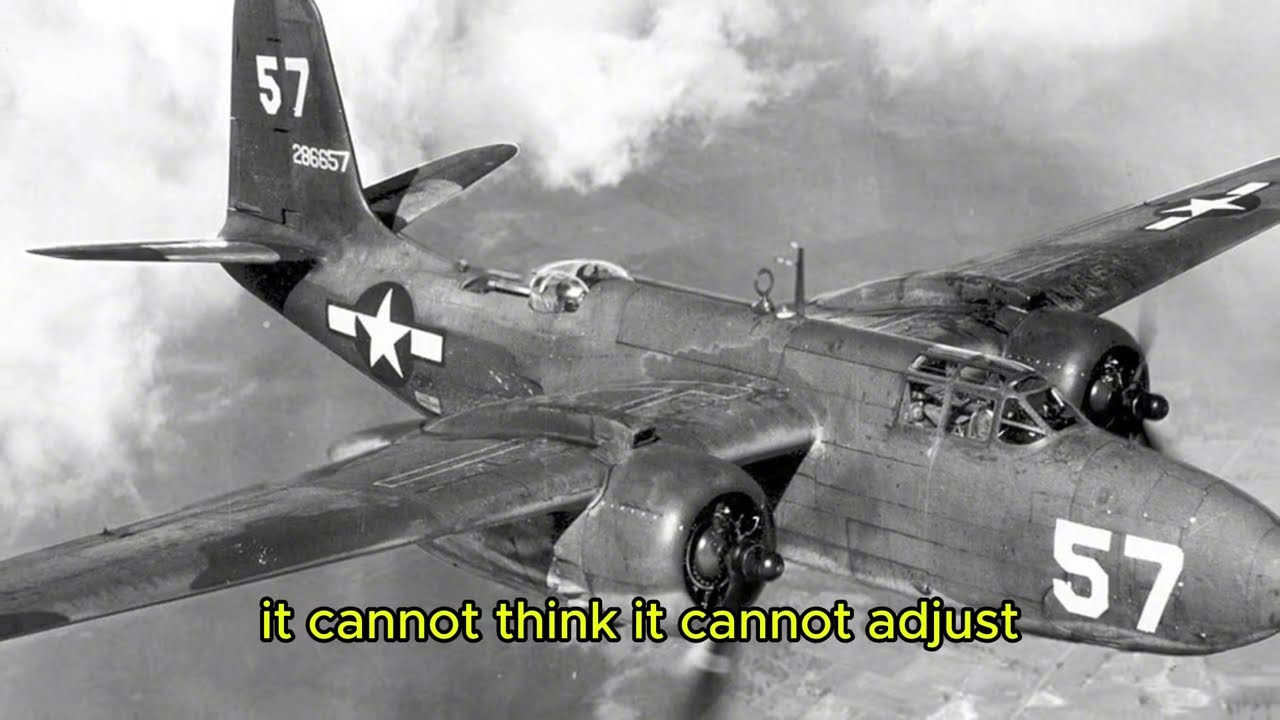

At best, the pilot would black out. At worst, the airplane would fold. This was not fear talking. This was math. The B-25 Mitchell was a sturdy aircraft, but it was still aluminum, thin skin, riveted structure, designed to carry bombs internally, not absorb the shock of a tank gun firing forward. The reports used clinical language, structural fatigue, center of gravity failure, unreoverable stall.

But in the margins in conversations, another phrase kept appearing. Pilot suicide. I want to pause again here because this is where modern viewers tend to assume someone ignored the experts. That is not what happened. The experts were heard fully carefully. And then the situation made their warnings irrelevant.

Out in the Southwest Pacific, the problem was not theoretical. Japanese destroyers were unloading troops in daylight. Barges were feeding entire island garrisons. American air power was watching it happen from above, helpless. Every day this continued, the strategic position worsened. General Kenny understood something that does not show up on blueprints.

A perfect aircraft that cannot solve the problem is still useless. He did not argue the equations. He accepted them. Then he accepted the consequences. He was not asking for permission to build something safe. He was ordering the creation of something necessary. The modifications began far from clean laboratories. They happened in sweat soaked hangers in Australia and New Guinea.

The B-25’s glass bombardier nose designed for precision bombing was cut off entirely. Sores, torches, no ceremony. In its place went a blunt steel nose, ugly and heavy, designed to hold the massive breach of the cannon. To keep the aircraft from tipping forward on the runway, mechanics bolted hundreds of pounds of lead into the tail.

Not elegant solutions, desperate ones. The interior was gutted. The navigator’s station disappeared. The bombardier’s role vanished overnight. His job no longer existed. In his place stood a new crewman with perhaps the most dangerous task in the Air Force, the canineer. His job was to stand next to the pilot, brace himself against turbulence, and manually load 15 lb artillery shells into the gun while flying at combat speed.

There was no automation, no safety buffer, just muscle memory and timing. Every additional calculation made the airplane worse on paper, heavier, slower, less stable. Test pilots described it as handling like a dump truck with wings. Engineers shook their heads. This machine violated everything they had been taught. I find this part deeply uncomfortable because it forces an honest question.

At what point does caution become complicity? The first ground tests were tense. Tax your unstrained landing gear. The nose sagged. The controls felt sluggish. Nobody knew what would happen when the trigger was pulled for real. The recoil system designed to absorb over 20 in of barrel movement was the only thing standing between the pilot and a broken neck.

When the aircraft finally lifted off for its first lift fire test, it used nearly the entire runway. The target was an empty reef. No enemy fire, no variables except physics. The pilot lined up, the gun was loaded, the cockpit went quiet. This was the moment the engineers had predicted would end the experiment.

The trigger was pulled. The aircraft shuddered violently. Smoke filled the nose. The sensation, according to those on board, was like flying into a solid wall. And then something unexpected happened. The plane kept flying. The wings held. The structure absorbed the shock. Down below, the shell hit exactly where the pilot aimed.

The math had been wrong, not because the engineers were careless,but because reality was messier than equations. In that instant, the idea crossed an irreversible line. It was no longer insane. It was proven. And once a weapon proves it can survive being fired, the only question left is what it can do to the enemy.

That answer would come soon and it would come at very low altitude. Once the gun proved it would not tear the airplane apart, everything else had to change. Not slowly, immediately. The B-25 was no longer a bomber in the traditional sense. It was now a weapon that demanded an entirely different way of thinking, flying, and surviving.

A bomber pilot is trained to be steady, smooth inputs, level flight, predictable motion so gravity can do the work. None of that applied anymore. The 75 mm cannon was fixed rigidly in the nose. It could not swivel. It could not elevate. The only way to aim it was to aim the entire aircraft.

That meant the pilot became the fire control system. To hit a target, he had to point 20 tons of airplane directly at it, hold it steady through turbulence, recoil, and fear and trust that his hands would not flinch at the last second. There was no margin. At low altitude, a mistake measured in fractions of a second was fatal. Training manuals were rewritten almost overnight.

Old habits were actively dangerous now. Crews practiced diving at derelic shipwrecks, learning how the sight picture changed as speed increased. At 200 mph, the ocean rushed toward them faster than instinct could comfortably accept. At 300 ft pers, targets grew alarmingly large, alarmingly fast. Effective range on paper was thousands of yards.

In combat, pilots quickly learned the truth. To guarantee a hit, they had to close to under 1,000 y, often closer, sometimes close enough to see individual sailors on deck. I need to stop here and say this plainly. This was not bravery as a personality trait. This was trained nerve, something built deliberately through repetition and fear management.

You don’t drift into this kind of flying. You force yourself into it. The attack profile became brutally simple. Descend to wave height. Use terrain or cloud cover to mask approach. Accelerate. Line up. Suppress deck guns with machine gun fire. Hold steady. Fire the cannon. Recover from recoil. If you survive the first pass, do it again.

The rate of fire was painfully slow. Three rounds per pass. If the canineer was strong and lucky. Each shell weighed 15 lb. Under G forces, it felt heavier, much heavier. The canoner had to brace his legs, wrestle the shell into the brereech, slam it shut, then signal the pilot all while the aircraft shook and enemy fire clawed at the fuselage.

Inside the cockpit, communication became rhythmic, short, sharp, load, ready, fire, clear, load, ready, fire. There was no room for hesitation. Any delay meant more exposure, more time inside the enemy’s envelope, and the enemy adapted quickly. Japanese gunners were experienced, disciplined. They understood aircraft attack profiles.

When they saw a bomber coming in low, they assumed torpedoes. The standard response was to turn the ship headon, presenting the narrowest possible target and ruining the torpedoes run against the gunship. That instinct became a trap by turning toward the aircraft destroyers unknowingly aligned their most vulnerable spaces, boilers, engines, magazines directly into the cannon’s path.

The very maneuver that had saved them for months now delivered them to the shot. I find this detail unsettling because it shows how deeply habit can betray even competent commanders. The Japanese captains were not foolish. They were experienced. They were simply responding to a threat that no longer existed.

The first operational targets were not destroyers. They were barges. Small cargo vessels hugging coastlines, feeding island garrisons. wooden hulls, light steel, minimal armorament. Against bombs, these targets often survived. A bomb could punch straight through and fail to detonate. Against the cannon, they did not survive at all.

One shell was usually enough. The impact did not sink the barge. It erased it. Fuel ignited, cargo detonated, crews vanished. The psychological effect was immediate. Pilots returned wideeyed, shaken not by danger, but by how final the destruction was. Word spread fast. What had been called a suicide box was now being called something else.

A hammer, a can opener, the lil monster. Crews began volunteering. Not because it was safer, but because it worked. More guns were added. Heavy 50 calibers clustered around the cannon, creating a storm of lead that stripped decks clean before the artillery round arrived. The configuration was refined into what crews called the Commerce Destroyer.

Not subtle, not elegant, effective. From a strategic perspective, this mattered more than anyone initially realized. Every barge destroyed meant fewer troops at the front, less ammunition, less food. In jungle warfare, logistics are everything. Cut them and even eliteunits wither. I’ll give you my honest reaction here.

This is the moment the story stops being about a weapon and starts being about leverage. One airplane did not win the war, but it changed how pressure could be applied. By mid 1942, Japanese commanders noticed the pattern. Daylight movement became dangerous. Supply run shifted to night. Routes became longer, slower, riskier. Every adjustment carried cost.

And still the destroyers remained fast, confident, untouched. The true test had not yet arrived. Everyone involved understood that barges were practice. The real question had been hanging in the air since the first cannon was bolted into place. Would this thing work against a warship that could fight back? That answer was coming soon, and it would arrive at 50 ft above open water.

The real test arrived without ceremony. Late 1942, patchy clouds hung low over the Bismar Sea. Visibility was uneven, unpredictable, the kind of weather that punished hesitation. Below the clouds, a Japanese convoy moved south. Vast transports guarded by fleet destroyers. Steel hulls, disciplined crews, anti-aircraft guns already manned.

These were not barges. These were hunters. From the air, the convoy looked confident. The destroyers cut clean wakes at over 30 knots, zigzagging just enough to complicate attack geometry. Their captains had survived months of bombing runs. They had watched bombs fall from the sky and miss by hundreds of yards. They expected the same today.

They were wrong. The American aircraft did not climb. They did not level off. They descended through cloud gaps down into the spray. Engines pushed hard. Propellers kicked water as the bombers leveled out at roughly 50 ft above the surface. Low enough that waves blurred into streaks. Low enough that error meant instant death.

The destroyer spotted them immediately. Orders were shouted on the bridges, guns elevated. Tracers reached upward, tearing through air that moments earlier had felt empty. From the Japanese perspective, this looked like madness. A medium bomber charging headon into naval gunfire. No torpedo drop, no pull-up, no evasion. The lead destroyer turned sharply to face the attack, presenting its bow, following doctrine drilled into every naval officer. Narrow the target.

Break the run. Survive. That decision sealed its fate. Inside the lead aircraft, the pilot’s world narrowed to the ring site mounted on the dashboard. No instrument mattered anymore. Airspeed, altitude fuel, none of it changed the equation. The gun was fixed. The target was growing. He held the line.

At 12,200 yd, the nose guns opened up. 50 caliber rounds poured forward, hammering the destroyer’s bow, raking the bridge, smashing rangefinders, forcing exposed gunners down behind shields. The returned fire faltered just enough. 600 yd. The cantoner wrestled the shell into place. 15 lb of steel and explosive. Breach closed.

His hand slapped the pilot’s shoulder. Ready? I want you to understand how close this was. At this distance, the destroyer filled the windshield. There was no sense of motion, only expansion. The gray wall rising faster than instinct could accept. The pilot lifted the nose a fraction, aiming not at the deck, not at the turret, at the water line, just below it, where boilers lived, where power became vulnerability. He fired.

The aircraft shuddered violently as if struck by something solid. Smoke blasted back along the fuselage. For a heartbeat, vision disappeared. The plane slowed sharply, physics asserting itself in a brutal reminder of mass and force. Then the view cleared. The shell crossed the remaining distance in under one second.

It struck steel just above the water line, punched through plating, tore through an internal bulkhead, and detonated inside the destroyer’s machinery spaces. Steam erupted. Metal twisted. Power failed instantly. On the bridge, Japanese officers felt the deck lurch. The ship began to lose speed. Not gradually, immediately. The white wake behind it thinned, then vanished altogether.

A 2,000 ton warship was dead in the water. The bomber screamed overhead so close that crewmen could see bodies thrown across the deck below. As the pilot pulled into a climbing turn, the cantoner was already moving, muscles burning as he hauled another shell into position under crushing G-forces. The second pass came faster.

This time there was no surprise. Japanese sailors scrambled to remman guns, fear breaking the discipline that training had built. Tracers reached out again, wilder, now less controlled. The pilot lined up on the stern. The machine guns fired. Deck crews scattered. The cannon roared again. The second shell struck near the depth charge racks.

The explosion that followed was not just artillery. It was secondary fuel, ammunition, stored explosives. A fireball erupted from the aft section. Debris arked into the sky. The shock wave rippled across the water, visible even from altitude. The destroyer shuddered, then began tosettle around it. The rest of the convoy tried to scatter, but the rules had already changed.

Other aircraft dropped lower. Skip bombing runs followed. 500lb bombs skipped across the surface like stones slammed into hulls detonated on contact. Within minutes, the convoy was chaos. Burning transports, crippled escorts, oil slicks stretching for miles. What had been a confident reinforcement force was now a graveyard. I want to be honest about something here. This was not elegance.

It was brutality applied with precision. The kind of violence that leaves no ambiguity about cause and effect. The destroyer did not sink because it was outgunned by another ship. It did not fall to a submarine or a battleship broadside. It was beaten by an airplane firing a weapon that should never have flown.

As the bombers turned for home, radios crackled with disbelief and adrenaline. Laughter, shouting, relief. Not celebration. Release. the kind that comes after surviving something that should have killed you. Behind them, smoke marked the water where doctrine had failed. In that moment, something fundamental broke. The surface ship was no longer king.

Speed no longer guaranteed safety. Steel could be reached from the air in ways no one had prepared for, and every naval commander in the Pacific would feel the consequences of that realization, whether they understood it yet or not. The effect was immediate, and it did not stay local. News of the engagement moved faster than official reports.

Pilots talked. Crews compared notes. Reconnaissance photos confirmed what radios struggled to describe. Ships that should have been operating with confidence were burning in daylight. Not from above, from the side, from the front, from impossibly low altitude. Japanese naval commanders reacted the way professionals always do when a rule breaks. They changed behavior.

Daylight movement began to disappear. Convoys that once steamed openly now waited for darkness. Routts bent closer to coastlines, hugging islands, weaving through narrow passages that limited speed and maneuver. What had been efficient became cautious. What had been fast became slow. Every adjustment carried a cost.

Running at night reduced visibility and increased the risk of collision. Longer routes burned more fuel. Slower speeds meant fewer deliveries. Supplies began arriving late, incomplete, or not at all. In island warfare, this was not an inconvenience. It was a countdown. I want to underline this point because it is where tactics become strategy.

The cannon did not just sink ships. It forced decisions. And decisions create friction. Japanese destroyers were still powerful, still fast, still dangerous. But now they were reacting instead of acting. The initiative had shifted, and once that happens, recovery is rare. Allied air planners noticed the change quickly.

Reconnaissance flights saw fewer ships by day. Radio intercepts hinted at rescheduled runs and altered plans. The ocean, once wide and permissive, was shrinking. The Battle of the Bismar Sea made this shift undeniable. When a major Japanese reinforcement convoy attempted to move troops and equipment toward New Guinea, it did so under the assumption that speed and escort strength would be enough. They were not.

Aircraft attacked at wave height. Gunship suppressed defenses. Skip bombing followed. Transports were torn open. Destroyers were crippled. In the span of a single engagement, an entire reinforcement effort was annihilated. The numbers were stark. Thousands of troops lost. Tons of supplies sent to the bottom. And more importantly, the confidence that those operations were even possible evaporated.

From that point on, Japanese planners had to assume that any daylight movement risked annihilation. That assumption reshaped the campaign. This is where I think the historical weight often gets diluted. People focus on the spectacle, the big gun, the low-level attack. But the real impact was logistical strangulation. An island army without food does not fight.

An airfield without fuel does not fly. A garrison without ammunition does not hold. Every ship that failed to arrive on time weakened the entire defensive network. The cannon forced a simple, brutal truth. Surface ships were no longer insulated from air power simply by speed. The ocean was no longer a shield. From the Allied perspective, this unlocked something critical.

Air power was no longer just about attrition from above. It became a tool of denial. Deny movement, deny resupply, deny choice. I’ll give you my personal assessment here. This was one of those moments where the war tilted not because of a single victory, but because of a change in expectation. Once commanders expect losses, they act differently, more cautiously, more slowly.

And in wartime favors the side applying pressure. The cannon itself was not perfect. It was heavy, difficult to use, demanding on crews. Losses still occurred. Low-level attacks were unforgiving. One mistake,one lucky hit from a ship’s gun, and an aircraft vanished. But effectiveness does not require perfection.

It requires leverage. And leverage is exactly what this weapon provided at exactly the right moment. By late 1942 and into 1943, production priorities shifted. The B-25 gunship variants entered full service. Crews trained specifically for maritime strike. Tactics evolved. Suppression, skip bombing, coordinated runs.

The Pacific War became less about single dramatic battles and more about sustained pressure. Choke points tightened. Supply lines frayed. Islands that had once been viable became liabilities. From the Japanese side, the change was visible in behavior. Convoys delayed, movements postponed, opportunities missed. Every night run carried risk.

Every delay compounded shortage. This is the kind of impact that rarely gets a headline. There is no single photograph that captures it. But it shows up in outcomes, in abandoned positions, in failed offensives, in quiet withdrawals. The gunship did not win the war by itself. No weapon does. But it changed the environment in which the war was fought. It compressed space.

It compressed time. It punished predictability. And once that environment changed, the advantage could not be easily reversed. By the time new technologies arrived, rockets improved fighters, more flexible strike options. The damage was already done. The lesson had been written into practice. Airplanes could reach into steel ships and break them open.

Not someday, not with perfect conditions, but now. And that realization haunted every naval operation that followed. By 1944, the 75mm cannon was already becoming obsolete. Not because it failed, but because war never waits for sentiment. New tools arrived. Airto ground rockets, lighter, faster, easier to aim. Fired in salvos instead of single brutal punches.

They required less nerve, less physical strength, less exposure. From a purely operational standpoint, the cannon was inefficient. It demanded elite pilots, human loaders, perfect timing, one miscalculation, and the aircraft paid the price. Rockets did the same job with fewer risks. The logic was undeniable.

So, the big gun came out. The B-25 evolved again. Solid noses filled with machine guns, rocket rails under the wings. The flying artillery that had terrified destroyer crews faded quietly into surplus yards and scrap piles. The cannon once the center of controversy was unbolted and forgotten. On paper, this looked like vindication for the engineers.

And that’s where the story becomes uncomfortable. Because if the cannon had truly been a mistake, it would not have left a legacy. Bad ideas disappear completely. This one didn’t. Two decades later, in a different jungle, the United States Air Force mounted heavy guns onto a transport aircraft and let it circle targets while raining fire from the sky.

the AC-47, then the AC-130, 40mm cannons, eventually a 105 mm howitzer, artillery in the air. The concept was the same, only the technology caught up. I want you to sit with that for a moment. The idea the experts called suicide did not die. It waited. So were the engineers wrong. This is the part most documentaries dodge.

They want a villain or a hero. Reality refuses to cooperate. The engineers were right about the risks. Every calculation they ran was grounded in real physics. They were doing their jobs. They were protecting crews from catastrophic failure. In any other context, they would have been praised for caution. But war does not reward caution equally on all timelines.

General Kenny was not smarter than the engineers. He was not ignoring science. He was weighing different deaths. The death of aircraft versus the slow death of a campaign that could not stop enemy logistics. That is the moral tension at the center of this story. On one side, responsible restraint.

On the other, desperate necessity between them. Young crews climbing into aluminum aircraft, knowing the trigger might kill them before the enemy ever could. This is why I think this moment matters far beyond one weapon. It exposes something permanent about warfare. Innovation does not come from comfort. It comes from failure.

And failure compresses decision-m until risk becomes acceptable. The cannon’s career was short. Its impact was not. It broke the illusion that surface ships were safe from low-level air attack. It forced behavioral change. It bought time. It strangled supply lines when nothing else could. It altered expectations. And expectations decide wars long before treaties do.

So, here is the question I want you to answer honestly. If you were an engineer in 1942 looking at those stress charts, would you have approved this aircraft? Comment the number seven if you believe the engineers were wrong and the risk was justified. Hit like if you disagree. If you believe this weapon crossed a line that should never have been crossed.

And if you want more stories like this, stories where theoutcome was not obvious and the decisions were never clean, subscribe to the channel. Because World War II was not won by perfect ideas. It was won by people willing to act when perfection failed. And that truth is still uncomfortable

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.