Iraq Sent Tanks — US Marines Stopped Them Without Using Tanks

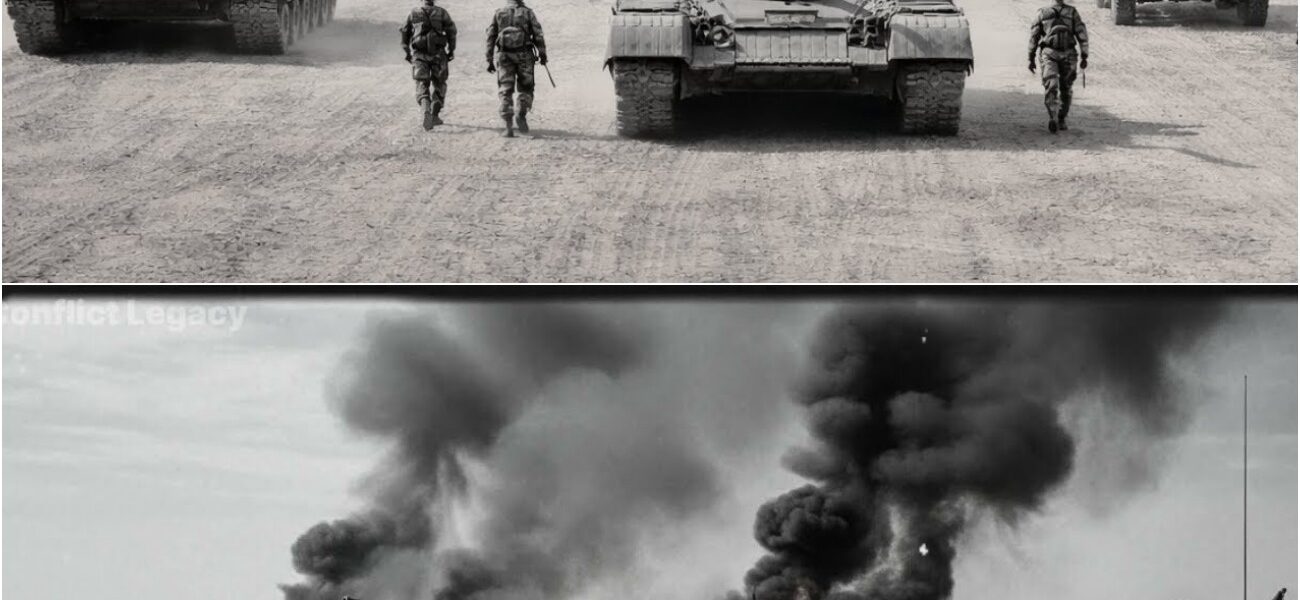

It’s January 29th, 1991, just after dusk. There is no moon, none at all. The border between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia is nothing but a black ribbon of sand and silence. To the naked eye, the desert looks dead. But in war, naked eyes are always the first to lie. Inside an Iraqi T-55, the air is thick and hot. The metal still holds the heat of the day.

It smells of diesel dust and old sweat. The commander grips the rim of the hatch while the radio crackles with short, tense orders. There is no heroic music here, just noiseheavy breathing and engines waiting for the signal. This is not a patrol. It is an invasion. Three armored and mechanized divisions are moving south. The objective is simple.

Cross the border sees Ka Gi and force the United States into a bloody ground war in Baghdad. The plan looks elegant, almost simple. If you push tanks against tanks, someone has to break. And this time, they are certain it won’t be them. Iraqi generals believe they understand the enemy. They believe the American public cannot stomach body bags coming home.

They believe their men, hardened by eight years of war with Iran, know what real combat feels like. Compared to that, the Americans seem fragile. Too much technology, not enough nerve. At least that’s what the charts say. Tonight, they expect a classic duel. Steel against steel, gun against gun. The gunners have their anti-armour rounds loaded.

Everyone is waiting to see them appear. The blocky shapes of the M60s, or worse, the wide, terrifying shadow of the M1 Abrams. 70 tons of American certainty. Engines roar. Tracks begin to roll. The column moves into the darkness confident of one thing. When the fighting starts, they will know exactly what they are shooting at.

What no one asks, and perhaps they should, is a very simple question. What if the Abrams never come? The Iraqi column moves forward and the desert gives nothing back. No flashes, no muzzle fire, no thunder of heavy guns. Um, just black sand stretching to the horizon. To many, that feels reassuring. It means the enemy isn’t there. Or so they think. Engines rev higher.

The formation stretches out. When you see no resistance, you move faster. It’s an old rule of war. It’s also an old trap. Inside the vehicles, confidence starts to feel uncomfortable. Not fear yet, something worse. Doubt. Commander search for what they expect to find. The thermal glow of a turbine engine.

70 tons of armor doesn’t hide easily, even at night. They listen for the familiar grind of heavy tracks. But the desert gives nothing back. No heat, no sound, just silence. Optics sweep the horizon again and again. Green, black, green again. Nothing. No Abrams, no M60s, no obvious defensive line. For an army trained for a frontal clash, this isn’t calm. It’s disorienting.

Speed increases again. Maybe the Americans pulled back. Maybe the air campaign scared them away from close combat. Um, it’s a comforting thought. Too comforting. The kind that makes men loosen their grip without realizing it. But something feels wrong. The ground is too quiet, too clean. In war, absence is also information.

And this absence feels heavy. The column pushes on faster now, driven by the dangerous idea that what you can’t see doesn’t exist. No one says it out loud. But the same thought begins to creep into every vehicle. If the enemy isn’t here, why does it feel like someone is watching? Everything changes in a single second.

No warning, no countdown, just a red line slicing through the darkness like someone cut the night open. The lead tank simply stops existing. One moment it is steel weight and confidence. The next it is fire, smoke, and falling metal. The turret is blown free and lands on its side as if torn off in disgust. The radio explodes.

Overlapping voices shouting broken orders. Contact front. Contact front. Front where no one knows, no one sees anything. The commander spins his sights, searching for the logical enemy, the 70tonon monster that is supposed to be there. But the optics show only cold. Cold sand, cold night. The desert is empty.

Then the second hit comes and the third, not the boom of tank guns, something faster. Rhythmic thump thump thump thump like steel being beaten by a giant jackhammer. Tracers streak through the night in short, precise bursts. Too precise. Where are they firing from? Someone asks over the radio. No answer. No one knows. Gunners try to react.

Turrets begin to turn slowly, heavily. Too late. Every time they swing toward a flash, it’s already gone. It feels like fighting a mosquito. If the mosquito had missiles, then the other strikes appear. Slower, almost relaxed. Thin wires glint for a second in the green glow of optics. Guided missiles. They fly calmly like they have all the time in the world.

When they hit, there is no confusion. Steel opens. Fire blooms. Another tank is dead in place. The formation starts to break apart. Drivers break. Others surge forward. Some try to reverse. Theproblem is no one knows what they’re running from. There are no silhouettes, no clear targets, just fire coming from places that shouldn’t exist.

Inside the vehicles, the noise is overwhelming. Steel vibrates. Systems fail. Men shout orders that can’t be carried out. They aren’t fighting a visible enemy. Uh they’re fighting the idea that the enemy should be there and isn’t. They are firing into the darkness and now the darkness is firing back.

Far from the front, the air is cooler and the lights are steady. In the command post, uh, Iraqi officers listen to reports arriving in confused bursts, fragmented sentences, you know, coordinates that don’t line up, units calling for support without being able to explain what they’re fighting. They try to assemble the puzzle, um, but the pieces don’t belong to the same picture.

Someone says, “It must be infantry. It has to be.” Only infantry can move like that, appear, and vanish. Another officer shakes his head. Infantry doesn’t blow turrets off tanks from 2 kilometers away at night. So, the other option surfaces. It must be American heavy armor hidden, dug in. Someone asks the obvious question.

If they’re tanks, where is the heat from the engines? An uncomfortable silence follows. The problem isn’t the information, it’s the mindset. The doctrine they were trained in has no space for this scenario. According to the manuals, war is solved by clear numbers, thicker armor, bigger guns, uh, denser formations. It’s mathematics, more steel winds.

And if the enemy is light, then it’s just a delay, a speed bump. The conclusion comes quickly because it fits what they want to believe. This isn’t a main force. It’s a screen, a reconnaissance unit that got lucky. Um, the real American line must have pulled back. So, they make the decision that turns confusion into catastrophe.

They order the advance, ignore the harassment, push into Kafgi. Uh, on the map, the logic looks perfect. In the city, they argue technology loses its edge. Sensors don’t work well between buildings. Speed dies in narrow streets. There, the fight becomes close, dirty, human. Exactly the kind of war they believe they know.

It’s It’s a comforting idea. Too comforting. What they don’t see is that by entering the city, they aren’t closing the enemy’s trap. They’re closing their own. Columns stretch out. Supply lines tighten. Maneuver space disappears. Every street becomes a choke point. every intersection a potential grave. They think they’re forcing the Americans into a fair fight.

In reality, they’re driving into a place where they won’t be able to run, won’t be able to turn, and where every mistake will cost twice as much. Back in the command post, new arrows are drawn on the map. Everything looks under control. The problem is the map is showing a war that no longer exists. From inside the Iraqi tanks, the situation starts to feel absurd.

They aren’t being crushed by a bigger force. They’re being taken apart piece by piece by something small, fast, and irritating. Like an elephant surrounded by mosquitoes, realizing too late that size means nothing if you can’t hit back. American vehicles appear and vanish. They don’t stay. They don’t dig in.

They pop out from behind a dune fire and disappear before a turret can finish turning. Shoot and scoot. Simple, almost insulting executed with ruthless discipline. Iraqi gunners try to track them, but turrets are heavy. Every movement is slow. By the time the sights line up, the target is already gone. just dust and the humiliating feeling of aiming at a memory.

The weapon punishing them doesn’t sound right. It’s not the deep boom of a tank gun. It’s continuous. Thump, thump, thump. Inside the steel hull, the sound is physical. It rattles bones. It pounds the skull like a bell that won’t stop ringing. The 25 mm rounds don’t need to punch through the front armor. That’s not the game.

They go for the eyes, optics, sights. One hit can blind a crew. Other bursts sever hydraulic lines, freezing the turret in place. The tank remains intact, but it can’t fight. Then fuel ignites. Fire without penetration. This is mission kill. The tank doesn’t explode. It simply stops being useful. From the outside, it looks fine.

Inside, it’s smoke noise and panic. The psychological effect is brutal. Every burst feels like dozens of blows. Metal flakes break loose inside the armor. They don’t always kill, but they convince. They convince trained crews that staying inside is worse than leaving. Orders to hold. come over the radio, but discipline collapses when you can’t see, can’t move your gun, and don’t know where the next hit will come from.

A fortress that feels like a coffin doesn’t inspire bravery hatches open. Crews bail out coughing and confused abandoning tanks that still run. The Americans didn’t bend physics that night. They didn’t need to. They just had hit the system where it hurt again and again until the giant gave up. When daylight comes, the mystery doesn’tvanish. It becomes uncomfortable.

The morning light reveals what the night hid, and what appears offers no comfort. There are no deep track marks in the sand. No signs of 70 ton monsters. Instead, there are thin, clean lines crossing the desert, rubber wheels. For Iraqi officers, it’s a slap in the face. For decades, they were taught that wheeled vehicles are coffins on a tank battlefield.

Too light, too fragile, something that should die at the first shot. Yet, the smoking wrecks around them tell a different story. Not every vehicle that attacked them was the same, even if they looked identical in the dark. Among the cannon armed scouts were others nearly indistinguishable with a different purpose.

The Lavats didn’t announce themselves. They simply waited. The real difference wasn’t armor. It was eyes and distance. While Iraqi crews strained to see that through limited sights and primitive infrared, the Americans saw the battlefield clearly. Targets appeared sharp, cold, measured. Tow missiles were in no hurry.

They flew steady, guided as if following a ruler’s line. Their effective range was devastating by comparison, nearly 4 kilometers. At that distance, a T-55 at night wasn’t fighting. It was was guessing it. Its gun was dangerous only when it could see. And that night sight was a luxury. The equation was simple. Detected first, targeted first, hit first before an Iraqi crew could even confirm they were in a fight.

The missile was already on its way. This wasn’t combat. It was delayed execution. That’s why the report sounded impossible. Tanks dying without warning. Not because physics changed, but because the chance to react never existed. By the time the shot arrived, the decision had already been made kilometers away. Morning brings no comfort.

Only a cold truth. When the enemy sees first and shoots farther armor thickness stops mattering. The Iraqis didn’t lose because they lacked courage. They lost because they were fighting at a distance they didn’t understand. And in this battle, whoever measures first shoots first. When Iraqi tanks roll into the city, many believe the worst is over.

Narrow streets, low buildings, tight intersections. Here, they think technology loses its edge. This is close combat. Steel rules again. And tanks hide in alleys. Guns cover avenues. RPG teams climb rooftops. A knife fight in a phone booth. For a brief moment, it works. City noise replaces the desert. Shadows feel protective. Commanders breathe.

If the Americans come, they’ll have to come headon. They’ll have to show themselves. But the Americans don’t come that way. They don’t rush in. They stay outside watching, listening. um marking um on rooftops. Uh reconnaissance teams look down, not outward. They don’t fire, they whisper coordinates. For the Iraqis, it’s unsettling

No visible fight, yet something is tightening. Then the sky speaks. Not a roar, but a low, constant hum. High above unseen and unreachable fire falls with almost insulting precision. A vehicle exists. A moment later, it doesn’t. Inside the city, safe positions turn lethal. Walls don’t protect. Roofs betray. Darkness becomes a spotlight on the ground.

American light vehicles shift gears. No more distant harassment. Now they surge in fast, coordinated wolf packs. They appear on one street, turn hard fire, and vanish before anyone can respond. They don’t trade blows, they trade confusion. An Iraqi tank tries to swing its gun at an intersection. The turret grinds too slow. A hit from behind.

Fire. No duel, just punishment for facing the wrong way. Communications collapse. Orders arrive late or not at all. Soldiers shoot at empty windows. Others wait for an enemy that never shows itself. The city isn’t shelter anymore. It’s a cage. At one point, desperation peaks. Isolated units call for support meters from their own positions. Danger close.

The phrase, “No one wants to say it means burning everything nearby and hoping you’re still alive afterward.” When the dust settles, the lesson is clear. The city didn’t cancel American advantages. It multiplied them. Every building became a sensor. every street a firing channel. The fight stopped being two-dimensional. It became vertical layered everywhere at once.

The Iraqis entered believing steel would dominate close quarters. They left learning that when the enemy fights in three dimensions, there is no alley narrow enough to hide. When the smoke clears, the conclusion isn’t heroic. It’s uncomfortable. The Iraqi army didn’t lose because it lacked courage. It lost because it was fighting a war that no longer existed.

For hours, they reacted to events already in the past. Every delay to order, every slow turn, every decision made with outdated information pushed them further behind. That was the real battlefield, not the desert, not the city. Time. The Americans observed, oriented, decided, and acted faster. By the time Iraq understood what was happening, the next phase was already over. That time gapdestroyed everything.

Uh the Iraqi command system was heavy, centralized, rigid. Uh decisions had to go up, wait, and come back down. By then, they were useless. On the other side, every American vehicle was a node. A sergeant could change direction, call support, or disengage without asking permission from a chain of offices. It wasn’t chaos.

It was organized speed. For decades, Iraq was taught to trust steel. Thick armor, big guns, mass, but steel only matters if you know where to aim. When you can’t see what’s killing you, armor thickness becomes a comforting number in a manual and not much else. The tanks didn’t fail as machines. They failed as ideas.

They were built for another era, another enemy, another tempo against a system that thought and moved faster. They became obsolete before they stopped moving. And here’s the part that stings the most. This wasn’t the full American army. This wasn’t the heavy divisions. This was the Marine Corps. Light forces like scouts wheeled vehicles that according to doctrine shouldn’t have won.

The generals in Baghdad stare at their maps and realize too late they weren’t ambushed. They ran into the future. A future where wars aren’t won by who has more steel, but by who decides faster. And the most unsettling thought of all is this. If a light force could do this, what would have happened when the real tanks started their engines?

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.