The mass rescue of 7,000 Jews in fishing boats — The operation that shocked the SS. NU

The mass rescue of 7,000 Jews in fishing boats — The operation that shocked the SS

October 1st, 1943. Copenhagen Harbor. In less than 72 hours, 7,000 people will vanish from Denmark as if swallowed by the sea itself. And the Nazi war machine, the most efficient killing apparatus ever created, will be left grasping at shadows. This is not a story about an army, a general, or a grand military strategy. This is the story of fishermen who became smugglers, housewives who became spies, and taxi drivers who became heroes. All to pull off what the SS would later call an impossible humiliation.

Tonight, you’re going to discover how an entire nation conspired in silence to commit the greatest act of mass defiance against Hitler’s final solution, and why this story was almost erased from history. The question is not whether they succeeded. The question is how a country of just 4 million people under the iron grip of Nazi occupation managed to hide, transport, and rescue 95% of its Jewish population right under the nose of the Gestapo using nothing but fishing boats, courage, and a conspiracy so widespread that even the German soldiers began to look the other way.

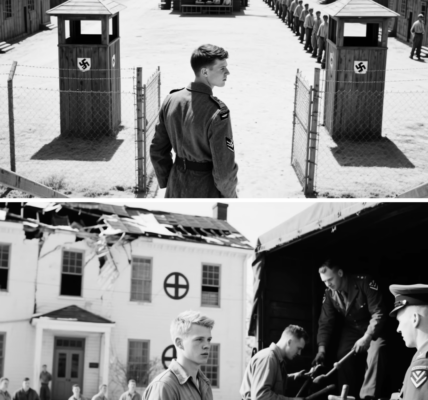

Denmark in 1943 was living a lie, and everyone knew it. On the surface, the small Scandinavian kingdom had become the model Nazi protectorate, the poster child of peaceful occupation that Hitler paraded to the world. Danish butter fed German soldiers. Danish factories produced parts for the Vermacht. King Christian I 10th still sat on his throne in Copenhagen, and the Danish police still patrolled the streets. There were no mass executions, no burning villages, no visible horrors like in Poland or France.

The Nazis called it the Aryan exception, a Germanic brother nation that had seen reason and submitted without blood. But beneath this facade of normality, something else was brewing, something the SS had not anticipated. The Danes were not collaborators. They were waiting. For 3 years, Denmark had walked a tightroppe, maintaining a fragile independence while Nazi troops stood on every corner. The government had cooperated just enough to keep the country functioning, to keep its people fed, and most importantly, to keep its 8,000 Jewish citizens safe.

Unlike almost every other occupied nation in Europe, Denmark had refused to implement the Nuremberg laws. There were no yellow stars in Copenhagen, no ghettos, no segregation. Jewish Danes were simply Danes, period. This was not an accident. This was a deliberate strategy of resistance disguised as compliance and it had worked for three long years. But in the fall of 1943, everything was about to change. Hitler was losing patience. The SS was demanding action, and a new name had arrived in Denmark to deliver what Berlin called the final accounting.

His name was Doctor Verer Best and he had been sent with one mission to make Denmark Uden free of Jews once and for all. Gayog Ferdinand Duckvitz did not look like a hero. At 40 years old, the German diplomat was overweight, nervous, and suffered from a guilty conscience that kept him awake most nights. He had joined the Nazi party early, climbed the ranks of the foreign office, and now served as a maritime atashe in occupied Copenhagen, a comfortable post far from the eastern front.

But on September 28th, 1943, Duckwitz sat in a meeting that would haunt him for the rest of his life. He learned that in exactly 3 days on the night of October 1st, the Gestapo would begin a coordinated raid across Denmark to arrest every Jewish man, woman, and child. The transport ships were already waiting in the harbor. The lists had been compiled. The SS had planned it down to the minute, and Duckwitz realized that unless someone did something in the next 72 hours, he would be complicit in the murder of thousands.

That night, he made a choice. What happened next was not a miracle. It was a conspiracy on a scale so massive that it involved fishermen, priests, doctors, students, resistance fighters, and even some German soldiers who simply refused to follow orders. It was illegal, dangerous, and should have been impossible. But in three desperate weeks in October 1943, Denmark accomplished what no other occupied nation had done. It saved its Jews. And the story of how they did it using fishing boats and darkness and raw human courage is one of the most astonishing rescue operations in the history of war and one of the most deliberately forgotten.

Gayorg Duckwitz was not supposed to be a savior. He was a bureaucrat, a functionary of the Reich, a man who had spent years convincing himself that his role in the machinery of occupation was administrative, not moral. But on the evening of September 28th, after leaving that meeting where the raid was finalized, Duckwitz walked the streets of Copenhagen for hours, smoking cigarette after cigarette, knowing that silence would make him a murderer. By midnight, he had made his decision.

He would betray the Reich. He contacted Hans Heed, the leader of the Danish Social Democratic Party, a man he barely knew but trusted to have the right connections. The message Duckwitz delivered was simple and terrifying. The Gestapo is coming in 3 days. They have the lists. They will arrest everyone and the trains to the camps are ready. Heft listened in disbelief. Then immediately understood what had to be done. The word had to spread and it had to spread fast but quietly enough that the Nazis would not catch wind of the warning.

What followed was a communication network that moved faster than telegraph wise. a whispered wildfire that reached from the synagogues of Copenhagen to the fishing villages on the coast. Within hours, the Jewish community of Denmark knew. Rabbi Marcus Melkor stood before his congregation on the morning of September 29th, the day before Rash Hashana, and told them not to return home. He told them to run, to hide, to trust their neighbors, and to head for the coast. There was no panic, no hysteria, only the cold realization that survival meant disappearing immediately.

Families packed what they could carry in a single bag. Elderly grandparents were helped into coats. Children were told they were going on an adventure. And then across Copenhagen, across every city and town where Jewish families lived, something extraordinary began to happen. Doors opened. Danish neighbors, people who had lived next to Jewish families for years, people who had shared meals and celebrated holidays together, stepped forward without hesitation. They offered their homes, their attics, their basement, their summer cottages.

They hid entire families in churches, in hospitals, in university dormitories. A network of safe houses materialized overnight, cobbled together by ordinary people who understood that this was not a political decision. It was a human one. But hiding 7,000 people was only the first step. Denmark is a small country and the Gestapo was thorough. The SS had done this in every occupied nation. They knew how to search. They knew how to find. If the Jewish population stayed in Denmark, they would eventually be discovered, rounded up, and deported.

There was only one option, evacuation. But where? Sweden. Neutral Sweden lay just across the Urasun Strait, a narrow stretch of water separating Denmark from safety. It was only a few miles at the narrowest point, but it might as well have been an ocean. The straight was patrolled by German naval vessels. The coast was watched by Vermach soldiers. Anyone caught attempting to cross would be shot or arrested on site. And yet, this was the only way out. The only question was how to move 7,000 people, most of whom had never been on a boat in their lives, across a militarized waterway guarded by the Third Reich.

The answer came from the most unlikely of sources, Denmark’s fishermen. These were not resistance fighters. They were not soldiers. Most of them had spent the war trying to stay out of trouble, catching cod and herring, selling their hall, and keeping their heads down. But when word spread through the coastal villages that Jewish families needed passage to Sweden, the fishermen did not hesitate. They did not ask for payment. They did not ask for guarantees. They simply began preparing their boats.

In the ports of Gilea, Neckston, Humlbec, and dozens of other small fishing villages, men began quietly stocking their vessels with extra blankets, removing fishing nets to make room for passengers, and studying the tide schedules and patrol patterns of the German Navy. They knew the waters better than anyone. They knew when the fog rolled in, when the moon would be dark, and where the German boats rarely ventured. What they were about to attempt was smuggling on an industrial scale, and the penalty for being caught was death.

Meanwhile, in Copenhagen, the Danish resistance scrambled to organize the logistics of what was quickly becoming the largest covert evacuation in European history. Safe houses were connected to a network of couriers, mostly students and young activists, who moved from address to address, guiding families to the coast under cover of darkness. Taxis became getaway cars. Ambulances transported the elderly and sick, marked with red crosses that the Germans rarely stopped. Fisherman’s wives prepared food for the journey. Priests forged identity documents.

Doctors sedated infants so they would not cry during the crossing. Every layer of Danish society was suddenly involved in a conspiracy of compassion. And the remarkable thing was that almost no one refused. There were no grand speeches, no declarations of resistance, just thousands of individual decisions made quietly to do the right thing. And in less than 72 hours, the impossible machinery of rescue was ready to begin. October 1st arrived like a countdown to catastrophe. At 8:00 that evening, the Gestapo launched their operation.

SS units fanned out across Copenhagen and every major Danish city. Armed with detailed lists of Jewish addresses compiled over months of meticulous surveillance, they knocked on doors with the cold efficiency that had worked in Warsaw, in Amsterdam, in Paris. But this time something was different. The doors opened to empty apartments. Furniture sat untouched. Dinner plates were still on tables. Beds were made. But the people were gone. House after house, street after street, the SS found nothing. The lists were accurate.

The addresses were correct. But the Jews of Denmark had vanished. In the first night of raids, the Gestapo managed to arrest fewer than 300 people, most of them elderly or sick individuals who had been unable to flee in time. Out of a population of nearly 8,000, the Nazis had caught less than 4%. It was an unprecedented failure, and the SS leadership was furious. Vera Best, the man who had ordered the raid, suddenly found himself scrambling to explain to Berlin how an entire community had evaporated under his watch.

But the Jews had not vanished into thin air. They were hiding, waiting, and moving toward the coast in a slow, dangerous migration that would take weeks to complete. The first boats left on the night of October Id. Small fishing vessels, no more than 30 ft long, designed to carry nets and a few crew members, were now loaded with 15, sometimes 20 people crammed into cargo holds that rire of fish and salt water. Families huddled together in the dark, instructed to stay silent, to not move, to barely breathe.

The fishermen navigated by instinct, cutting their engines as they approached the shipping lanes where German patrol boats circled like sharks. The crossing to Sweden under perfect conditions took less than an hour. But these were not perfect conditions. The nights were cold, the sea was rough, and the risk of detection was constant. Every light on the horizon could be a German search light. Every sound could be the engine of an enemy vessel. And if they were caught, the passengers would be arrested and the fishermen would be executed.

Yet boat after boat slipped into the night, running dark, running silent, carrying their human cargo toward the Swedish coast. But the operation was far from smooth. In the fishing village of Gillesia, over a 100 Jewish refugees had been hidden in the attic of the local church, waiting for transport. On October 6th, a Danish informant tipped off the Gestapo. The SS surrounded the church and arrested 80 people in a single raid. It was a devastating blow, a reminder that not every Dne was a hero, and that betrayal could come from anywhere.

The resistance learned quickly. They spread the evacuation out across dozens of small villages instead of concentrating people in single locations. They changed departure times, used decoy boats to draw German patrols away from the real crossings, and established a communication system using coded messages delivered by bicycle couriers. The operation became more sophisticated with each passing night, evolving from a desperate improvisation into something resembling a covert military campaign, except the soldiers were fishermen and housewives, and the battlefield was the cold, dark water of the Urasun Strait.

Meanwhile, on the Swedish side, another quiet miracle was unfolding. Sweden had remained neutral throughout the war, walking a delicate diplomatic line to avoid German invasion. But when the first boats began arriving with Jewish refugees, the Swedish government made a decision that surprised the world. They opened their borders. No quotas, no restrictions, no bureaucratic delays. Every Jew who reached Swedish shores was granted asylum immediately. Fishing boats were met by Swedish Coast Guard vessels that guided them safely to harbor.

Refugee centers were established overnight. Families were given housing, food, and medical care. The Swedish Red Cross mobilized hundreds of volunteers. And perhaps most remarkably, the Swedish government made it clear to Berlin that they would accept every single Jewish refugee from Denmark, no matter how many came. It was a diplomatic slap in the face to Hitler and it gave the Danish resistance the confidence to keep pushing, to keep sending boats, to keep fighting for every single life. By the second week of October, the operation had found its rhythm.

Every night, under cover of darkness, dozens of boats made the crossing. The Gestapo knew what was happening, but could not stop it. They increased patrols, interrogated fishermen, raided suspected safe houses. But the network was too large, too decentralized, too deeply woven into the fabric of Danish society. For every boat they intercepted, 10 more got through. For every family arrested, 50 escaped. The SS was not just losing. They were being humiliated by fishermen. The resistance fighters who coordinated the rescue were not seasoned spies or trained commandos.

They were university students, factory workers, and shop owners who had never fired a gun or planned a covert operation in their lives. But what they lacked in experience, they made up for in ingenuity and sheer audacity. In Copenhagen, a group of medical students turned the city’s ambulance service into a clandestine transport network. They forged documents claiming that Jewish families were gravely ill patients being transferred to coastal hospitals for emergency treatment. German checkpoints conditioned to wave through ambulances marked with red crosses rarely stopped to inspect the cargo.

Entire families, sometimes 10 or 12 people, would be hidden under blankets in the back of a single ambulance, their hearts pounding as they passed within feet of SS officers. The drivers, many of them barely in their 20s, kept their faces calm and their hands steady on the wheel, knowing that a single nervous glance could unravel everything. It worked almost every time. By mid-occtober, the ambulance route had become one of the safest and most efficient pipelines to the coast.

But not every escape went smoothly, and the risks were escalating. The Gestapo had begun conducting random searches of vehicles heading toward the fishing villages, suspicious of the unusual traffic flowing north from Copenhagen. On October 9th, a truck carrying 18 people, was stopped at a checkpoint near Helsinger, one of the busiest crossing points. The driver, a resistance member named Erling Kia, knew that if the Germans searched the back of the truck, everyone inside would be arrested and likely executed.

So he did the only thing he could think of. He pretended the truck had broken down, climbed out, lifted the hood, and began fiddling with the engine while loudly cursing in Danish. The German soldiers, annoyed and impatient, grew frustrated watching him struggle. After 10 agonizing minutes, they waved him through without inspecting the cargo, too irritated to bother with a broken down vehicle. Kia drove slowly away, his hands shaking so badly he could barely grip the steering wheel.

But the 18 people hidden in the back, made it to the coast and crossed to Sweden that same night. Stories like this, small moments of quick thinking and raw nerve, repeated themselves across Denmark. Each one a tiny victory that added up to something extraordinary. The fishing boats themselves became floating works of improvisation. To avoid detection by German patrol boats equipped with search lights, fishermen began hiding their passengers in secret compartments built beneath the deck, covering them with nets and layers of fish to mask any sound or movement.

The smell was suffocating, the air was stifling, and passengers often spent hours cramped in total darkness, fighting seasickness and terror in equal measure. On one crossing, a baby began to cry just as a German patrol boat approached. The mother, desperate and panicking, covered the infant’s mouth, but the child only cried louder. A fisherman made a split-second decision. He started his engine and began hauling in his nets, loudly shouting orders to his crew, creating enough noise to drown out the baby’s cries.

The German boat circled once, shining its spotlight across the deck, saw nothing but fishermen working their catch, and continued on. The mother clutched her baby and wept silently in the darkness below, unaware of how close they had come to disaster. By the third week of October, the sheer scale of the operation was beginning to overwhelm even the organizers. Thousands of people were still in hiding, scattered across hundreds of safe houses, waiting for their turn to cross. The demand for boats far exceeded the supply and the fishermen, exhausted from weeks of nightly crossings, were being pushed to their limits.

Tensions rose. Some families had been waiting for over a week, terrified that the Gestapo would find them before a boat became available. Money became an issue. While many fishermen refused payment, others facing the loss of their livelihoods and risking their lives began charging fees for passage. The Danish resistance determined that no one would be left behind because they could not afford the crossing organized a fundraising effort that spread across the country. Wealthy Danes contributed thousands of croner.

Churches collected donations. Even some German sympathizing Danish businessmen uncomfortable with the brutality of the SS quietly donated to the cause. Within days, enough money had been raised to cover the cost of every crossing, ensuring that rich and poor alike would have a chance at freedom. And then, just as the operation seemed to be hitting its stride, the Gestapo made a move that threatened to collapse the entire network. On October 18th, German forces raided the coastal town of Snecker, one of the key departure points, and arrested 12 fishermen in a single night.

Torture followed. The SS wanted names, locations, and schedules. They wanted to dismantle the rescue operation piece by piece. But the fishermen under interrogation said nothing. Some were beaten. Some were sent to concentration camps. But not one of them gave up a name. Their silence bought the resistance time. And within 24 hours, the evacuation routes shifted to new villages, new boats, and new departure times. The operation continued, relentless and unstoppable, driven by a collective defiance that refused to break.

The most dangerous crossings were not the ones in darkness, but the ones in desperation. As October wore on and the Gestapo intensified their searches, families who had been waiting in safe houses for weeks, grew increasingly terrified that their hiding places would be discovered. Some made the decision to attempt the crossing during daylight hours, a gamble that bordered on suicide. German patrol boats were far more active during the day, and the risk of being spotted by coastal vermach units was almost guaranteed.

But fear has a way of overriding logic. And in several documented cases, families chose the daylight risk over the uncertainty of waiting another night. One such crossing involved a group of 40 people crammed into a fishing boat designed for 10. The vessel sat dangerously low in the water, overloaded and unstable, barely able to move at more than a crawl. Halfway across the straight, a German patrol boat appeared on the horizon. The fisherman, a man named Kai Larsen, made a split-second decision that seemed insane.

Instead of cutting the engine and trying to hide, he throttled forward, speeding directly toward the German vessel, waving frantically as if signaling for help. The German crew, confused, slowed down to see what the commotion was about. Larsson shouted in broken German that his engine was failing and he needed a tow back to shore. The Germans, either convinced by the performance or simply unwilling to deal with the hassle, waved him off and told him to fix it himself.

Len immediately turned his boat towards Sweden and gunned the engine, not stopping until he reached Swedish waters. It was a bluff so audacious that it should not have worked, but it did, and 40 people lived because of it. Yet not every story ended in triumph. On October 13th, a boat carrying 32 refugees capsized in rough seas just a few hundred yards from the Swedish coast. The fisherman and his crew managed to rescue most of the passengers, dragging them from the freezing water, but four people drowned, including two children.

Their bodies were never recovered. The tragedy was kept quiet by the resistance, not out of shame, but out of necessity. If word spread that crossings were resulting in deaths, panic could set in, and families might refuse to attempt the journey, trapping them in Denmark, where the Gestapo was closing in. The fisherman who lost those passengers never spoke publicly about what happened, but those who knew him said he was never the same. He continued making crossings every night for the rest of October, as if trying to save enough lives to balance the ones he had lost.

The sea does not care about heroism, and the resistance learned that even the best plans could be undone by a rogue wave or a sudden storm. But they kept going because stopping was not an option. Meanwhile, the Swedish response to the influx of refugees was becoming a logistical operation in its own right. By the middle of October, over 5,000 Jewish Danes had arrived on Swedish shores, and the numbers were growing every night. The Swedish government, working with the Red Cross and Jewish aid organizations, established reception centers in every coastal town facing Denmark.

Volunteers met the boats as they arrived, providing blankets, hot food, and immediate medical attention. Many refugees arrived suffering from hypothermia, seasickness, and shock. Some had been at sea for hours. Others had been hiding in freezing compartments for half the night. Swedish doctors and nurses worked around the clock, treating everything from frostbite to heart attacks brought on by stress. What is remarkable is that Sweden did not treat this as a crisis to be managed but as a moral obligation to be fulfilled.

There was no debate, no political grandstanding, no bureaucratic red tape. The message from Stockholm was clear. Every Danish Jew who reaches our shores will be safe. No exceptions. It was one of the few moments in World War II where a neutral nation took an unambiguous moral stand and it made all the difference. Back in Denmark, the Gustapo was growing increasingly desperate and erratic. Vera Best, facing mounting pressure from Berlin to explain how the deportation operation had turned into such a catastrophic failure, began ordering random arrests of Danish citizens suspected of aiding the resistance.

Fishermen, doctors, priests, and students were dragged in for interrogation. Some were tortured. Some were sent to German prisons. But the crackdown had the opposite effect that the SS intended. Instead of intimidating the Danish population into submission, it hardened their resolve. More people joined the resistance. More boats made the crossing. More families were hidden. The network expanded rather than contracted, and the message to Berlin was unmistakable. You cannot terrorize an entire nation into betraying its neighbors. Denmark had made its choice and no amount of Gestapo brutality was going to change it.

By October 20th, nearly 6,000 people had successfully crossed to Sweden. The operation, which had started as a panicked improvisation, had become one of the most efficient rescue missions of the entire war. But there were still over a thousand people in hiding, scattered across Denmark, waiting for their chance to escape. The resistance knew that time was running out. Winter was approaching. The seas were getting rougher, and the Gestapo was tightening its grip. The final push was about to begin, and it would require every ounce of courage the Danish people had left.

The final week of October brought a new level of danger that tested the limits of what the resistance could endure. The Gestapo, humiliated by the mass escape and facing relentless pressure from Berlin, shifted tactics. Instead of random raids, they began employing informants. Danish collaborators who infiltrated safe houses and pretended to be sympathetic helpers. These double agents would gain the trust of hiding families, learned the evacuation schedules, and then tip off the SS at the last possible moment.

On October 22nd, one such informant led the Gustapo to a farmhouse outside Copenhagen where 17 people were waiting for transport. The raid happened at dawn before the families even had a chance to flee. All 17 were arrested and deported to Terzian concentration camp within 48 hours. It was a brutal reminder that betrayal could come from anywhere and the resistance responded by tightening security protocols. Trust which had been freely given in the early days of the rescue now had to be earned.

Couriers used code words. Safe houses were changed every few days, and anyone who could not be vouched for by at least two resistance members was turned away, no matter how desperate their story seemed. Despite the tightening noose, the fisherman continued their relentless nightly runs, and some of the most extraordinary acts of courage came in these final days. A fisherman named Thorn Len, who had already made over 30 successful crossings, took on one last mission on the night of October 25th.

His boat was old, his engine unreliable, and he had been warned by fellow fisherman that the German patrols had increased their presence near his usual crossing route, but a family of six, including an 80-year-old grandmother who could barely walk, had been waiting for a week, and no other boat was available. Len agreed to take them. Halfway across the straight, his engine failed. The boat went silent, drifting in the current, completely exposed. Within minutes, the beam of a German search light swept across the water, heading directly toward them.

Larsson made a decision that defied every instinct of survival. He dove into the freezing water, swam under his own boat, and began manually repairing the engine in total darkness, holding his breath for over a minute at a time, while his passengers sat frozen in terror above him. It took him nearly 20 minutes, but he got the engine running again just as the German patrol boat was close enough to hail them. Len climbed back aboard, soaking wet and shaking from cold, fired up the engine, and made it to Sweden.

He never spoke about what he did that night, but the family he saved told the story for the rest of their lives. The pressure on the remaining Jews in hiding was unbearable. Families had been living in atticss, basements, and church crypts for nearly a month, surviving on scraps of food, unable to leave, unable to make noise, living in constant fear that the next knock on the door would be the Gestapo. Children had to be kept quiet, often sedated with small doses of medicine provided by sympathetic doctors.

The elderly and sick, unable to endure the harsh conditions of hiding, were deteriorating rapidly. Some families debated whether to simply turn themselves in, exhausted by the psychological torment of waiting. But the resistance kept pushing, kept promising that every single person would get out, that no one would be abandoned. And in those final days, the Danish people pulled off feats of logistical brilliance that would have impressed a trained military. A network of taxis operated around the clock, shuttling families from safe houses to coastal villages, using routes that change daily to avoid checkpoints.

Bicycle couriers relayed messages about patrol schedules and weather conditions. Even Danish police officers, officially servants of the Nazic controlled government, began leaking information about upcoming Gestapo raids, giving the resistance just enough warning to move people to safety. On October 28th, the largest single crossing of the entire operation took place. Over 200 people were evacuated in a single night using a flotilla of 12 fishing boats that departed simultaneously from three different villages. It was a coordinated effort that required perfect timing and absolute silence.

The boats left at staggered intervals, navigating through fog so thick that the fisherman could barely see 10 ft ahead. German patrol boats passed within shouting distance, their search lights cutting through the mist. But the fog was so dense that the fishing boats remained invisible. All 12 vessels made it to Sweden without a single arrest. It was the closest thing to a military operation the resistance had ever attempted. And its success proved that even after a month of constant pressure, the network was not breaking.

It was adapting, evolving, and becoming stronger. By the end of October, the numbers told a story that even the SS could not spin into victory. Of the nearly 8,000 Jews living in Denmark at the start of the month, over 7,000 had escaped to Sweden. Only 482 had been captured and deported, most of them in the first chaotic days before the network was fully operational. The survival rate was over 95%, the highest of any occupied nation in Europe.

The operation had cost the lives of several resistance members and a handful of refugees who had drowned or died during the crossings. But compared to the systematic annihilation happening across the continent, Denmark had achieved something miraculous. But the story was not over. The final act was still to come, and it would reveal just how deep the conspiracy had gone. By early November, the rescue operation had officially ended. But the story that emerged in its aftermath was almost as shocking as the escape itself.

Historians and resistance members who documented the events began piecing together a conspiracy so vast and so deeply embedded in Danish society that it defied belief. It was not just fishermen and students who had participated. It was police officers, government officials, Lutheran bishops, and even elements of the Danish military that had operated under Nazi supervision. The entire country, from the highest levels of government down to the dock workers loading German supply ships, had conspired to sabotage the final solution on Danish soil.

And what made the story even more astonishing was the discovery that some German officials stationed in Denmark had not only turned a blind eye to the rescue operation, they had actively assisted it. Gayog Dukitz, the diplomat who had first warned the Jewish community, was not alone. Several German military officers, disillusioned with the SS and horrified by the deportation orders, had quietly leaked patrol schedules, delayed inspections, and in at least one documented case, redirected a German patrol boat away from a known crossing route.

These were not acts of organized resistance, but individual moral choices made by men who realized they were being asked to participate in mass murder and refused. The full scope of this internal sabotage within the German military did not become clear until after the war when interrogations and declassified documents revealed just how many German soldiers had quietly disobeyed orders during October 1943. Some of them faced reprimands. A few were reassigned to the Eastern Front as punishment, but none of them spoke openly about what they had done, and their acts of defiance remained hidden for decades.

What this revealed was something that terrified the Nazi high command more than any Allied bombing raid. The final solution only worked when people followed orders without question. And in Denmark, even some of the Germans had stopped obeying. The machinery of genocide required total compliance. And Denmark had proven that compliance could be broken not through armed rebellion, but through collective refusal. Hitler’s propaganda had always claimed that the extermination of the Jews was necessary. inevitable and supported by the people of Europe.

Denmark had just proved that it was none of those things. Verer Best, the Nazi official who had ordered the deportation and then watched it collapse in spectacular failure, found himself in an impossible position. He could not tell Berlin that an entire nation had conspired against him. He could not admit that German soldiers under his command had failed to carry out their orders, so he lied. In his official reports to Berlin, Best claimed that the deportation operation had been a success, that the majority of Denmark’s Jews had been arrested, and that the few who escaped had only done so because they had been tipped off by a small group of resistance terrorists.

He inflated the arrest numbers, fabricated stories of violent confrontations with armed partisans, and insisted that the situation in Denmark was under control. Berlin, distracted by the collapsing war effort on the Eastern front and the Allied invasion of Italy, largely accepted his version of events. Best remained in his position, outwardly maintaining the facade of Nazi authority while privately understanding that his career was destroyed. He had been sent to Denmark to deliver a final solution, and instead he had presided over the largest rescue of Jews in occupied Europe.

But the real question that haunted best and the SS leadership was not how the Jews had escaped, but why the Danes had helped them. This was not France, where the Vichi government had eagerly collaborated with the deportations. This was not Poland, where local populations had sometimes participated in poggrams. Denmark had no history of violent anti-semitism. There were no Jewish ghettos, no history of expulsions, no deep-seated hatred waiting to be exploited. The Danish people simply saw their Jewish neighbors as Danes, and when the Nazis came to take them, the response was not indifference or collaboration, but mass defiance.

The SS had expected fear and submission. What they encountered instead was a culture that valued human decency more than obedience to authority, and it broke the Nazi playbook completely. Germany had conquered Denmark militarily in a matter of hours, but they had failed to conquer it morally, and that failure exposed the fundamental weakness of the entire Nazi ideology. The rescue operation had proven something that the Allies, still years away from victory, desperately needed to believe, that ordinary people, unarmed and facing overwhelming force, could still resist.

That courage was not the exclusive domain of soldiers and spies. That a nation could stand up to evil without firing a shot. Denmark had shown the world that the Third Reich, for all its military might and propaganda, could be defeated by something as simple as collective goodness. And in the dark autumn of 1943, as the war ground on and the death camps continued their work across Europe, that lesson mattered more than any battlefield victory. The 482 Danish Jews who had been captured and deported to Terresianstat concentration camp were not forgotten.

In fact, their fate became the subject of one of the most bizarre and relentless diplomatic campaigns of the entire war. The Danish government, still nominally functioning under Nazi occupation, did something that no other occupied nation had dared to attempt. They demanded access to the prisoners. They sent Red Cross packages. They insisted on regular updates about their condition and most shockingly they made it clear to Berlin that if any of the Danish Jews in Theresian were transferred to extermination camps there would be consequences.

This was an unprecedented stance for a defeated occupied nation to take and the fact that the Nazis tolerated it revealed just how much Denmark had rattled the Nazi command structure. Vera Best desperate to maintain some semblance of control and avoid further embarrassment actually lobbyed Berlin to grant the Danish government limited access to Tesian arguing that it would calm tensions and prevent further resistance activity. Berlin shockingly agreed. Red Cross inspectors were allowed to visit the Danish prisoners and packages containing food, medicine and clothing were delivered regularly.

It was not freedom, but it was survival. And it meant that Denmark continued to fight for its Jewish citizens even after they had been taken. The reason the Nazis tolerated this interference was coldly pragmatic. Teresian was being used as a propaganda tool, a so-called model ghetto that the Nazis could show to international observers to counter reports of mass exterminations. The presence of Danish Jews whose government was actively monitoring their welfare actually served the Nazi narrative. It allowed them to claim that deportation did not mean death, that Jews were being resettled humanely, and that reports of gas chambers were allied lies.

But the Danish persistence had an unintended consequence. Because the Red Cross and the Danish government were watching Theresian so closely, the SS could not quietly liquidate the Danish prisoners the way they had done with Jews from other nations. Every Danish Jew had a paper trail, a name on a list that Copenhagen was tracking, and any unexplained disappearance would trigger immediate inquiries. So the Nazis kept them alive, not out of mercy, but out of political necessity. And when the war ended in May 1945, all but 51 of the 482 deported Danish Jews survived and returned home.

It was a survival rate unheard of for concentration camp prisoners, and it happened because Denmark refused to let them be forgotten. Meanwhile, in Sweden, the 7,000 Jewish refugees who had escaped were building new lives, but they never stopped thinking about Denmark. Many of them spent the remainder of the war working with the Swedish resistance, smuggling intelligence back into Denmark and supporting sabotage operations against German forces. Others joined Allied military units and fought their way back into Europe as the tide of the war turned.

They were not passive refugees waiting for liberation. They became active participants in the fight against Nazism, driven by a sense of gratitude and obligation to the country that had saved them. And when the war finally ended and Germany surrendered, thousands of Danish Jews returned home to find something almost miraculous. Their homes had been maintained, their businesses had been looked after by neighbors, their possessions had been protected. In most of occupied Europe, returning Jews found their properties looted, their homes occupied by strangers, and their communities destroyed.

In Denmark, they found their keys still worked, their furniture was still in place, and their neighbors welcomed them back as if they had never left. This was not accidental. During the entire period that the Jewish population was in exile, the Danish resistance had organized volunteers to maintain their properties, pay their rent, and protect their belongings from lutters or opportunistic neighbors. It was an extension of the same collective moral code that had driven the rescue in the first place.

You do not abandon your neighbors even when they are gone, even when no one is watching. The people who did this work were not looking for recognition or reward. They were simply doing what they believed was right. And their efforts ensured that the return of the Jewish community was not just a homecoming, but a restoration. Denmark had not only saved its Jews, it had preserved their place in Danish society, refusing to let the Nazis erase them from the national fabric.

But perhaps the most extraordinary detail of the entire operation, the one that historians still struggle to fully explain, is how few people betrayed the network. In 3 weeks of covert evacuations involving thousands of participants, only a handful of Danish collaborators leaked information to the Gestapo. In every other occupied nation, resistance networks were riddled with informants, torn apart by betrayal, and constantly operating under the threat of exposure. In Denmark, the level of secrecy and solidarity was so high that even the Gestapo, with all its resources and brutality, could not penetrate it.

This was not because the Danes were uniquely heroic or morally superior. It was because the operation was so widespread involving so many ordinary people that informing on the network would have meant informing on your neighbors, your friends, your family. The social cost of betrayal was simply too high, and the Nazi occupation had never succeeded in breaking the bonds of Danish civil society. The rescue worked because an entire nation became complicit in defiance, and that made it nearly impossible to stop.

The long-term consequences of the Danish rescue operation rippled far beyond the borders of that small Scandinavian nation and continued to shape history in ways that were not immediately obvious. In the immediate aftermath of the war, as the full scale of the Holocaust became known and the world confronted the reality that 6 million Jews had been systematically murdered, Denmark stood as a singular exception, a country that had said no and made it stick. But what made Denmark’s story even more powerful was what happened next.

In the Nuremberg trials and the subsequent war crimes tribunals, prosecutors used the Danish rescue as evidence to counter one of the most common defenses offered by Nazi officials. That they had no choice, that orders were orders, that resistance was impossible. Denmark proved that resistance was not only possible, it was achievable even under occupation, even without an army, even when facing the full machinery of the Third Reich. The judges at Nuremberg cited Denmark repeatedly when rejecting the defense of superior orders.

And the legal precedent established in those trials that individuals are morally responsible for their actions even under authoritarian regimes owes part of its foundation to what happened in Copenhagen in October 1943. Yet despite its significance, the Danish rescue operation was not widely celebrated or remembered in the decades immediately following the war. There were no Hollywood films, no major monuments, no global recognition. Part of the reason was Denmark itself. The Danes did not treat the rescue as an act of extraordinary heroism.

They treated it as ordinary decency, as something any civilized nation would have done, and they were uncomfortable with being singled out for praise when so much of Europe had failed. Danish fishermen who had risked their lives making dozens of crossings returned to their villages and went back to fishing. Students who had coordinated safe houses finished their degrees and became teachers and doctors. The taxi drivers, ambulance crews, and priests who had smuggled families to safety simply went back to their normal lives.

There was no victory parade, no national day of celebration, no effort to turn the rescuers into celebrities. In fact, many of them never spoke publicly about what they had done, and their children only learned the full story years later, often by accident. This silence was not born of modesty alone. It was also a reflection of how Denmark chose to process its wartime experience. Unlike France, which celebrated the resistance while downplaying collaboration, or Germany, which spent decades grappling with collective guilt, Denmark adopted a narrative of quiet universal resistance.

The country preferred to remember the war as a period when everyone in their own small way had stood against the Nazis and singling out individuals for heroism felt like a betrayal of that collective effort. The fishermen did not want statues. The students did not want medals. They wanted the story to be about Denmark, not about themselves. And so the rescue faded into a kind of understated national memory, acknowledged but not celebrated, honored but not mythologized. It was not until the 1980s and 1990s as Holocaust education became a global priority and survivors began sharing their stories more openly that the full scope of what Denmark had accomplished started to receive the international attention it deserved.

But even as the story gained recognition, it also became a source of uncomfortable questions for the rest of Europe. If Denmark, a small occupied nation with no military and limited resources, could save 95% of its Jewish population, why did other countries fail so catastrophically? Why did France deport 75,000 Jews? Why did the Netherlands lose 75% of its Jewish population? Why did Poland, despite having the largest Jewish community in Europe, see over 90% of its Jews murdered? These were not questioned cares with easy answers, and they forced a reckoning with the uncomfortable truth that the Holocaust required not just Nazi perpetrators, but also widespread indifference, collaboration, and in some cases, active participation by local populations.

Denmark’s success highlighted everyone else’s failure, and that made the story politically sensitive. Some historians pushed back, arguing that Denmark’s circumstances were unique, that its Jewish population was small and assimilated, that the Nazis had not prioritized Denmark the way they had Poland or Hungary, and that crediting the Danes with saving their Jews was an oversimplification. These arguments were not entirely wrong, but they also missed the point. Denmark’s circumstances were not unique. What was unique was Denmark’s response. The fishermen who made those crossings, the families who hid their neighbors, the diplomats who leaked warnings, and the Swedish government that opened its borders, all made choices.

They were not inevitable choices. They were moral decisions made under pressure, often at great personal risk. And they proved that the Holocaust was not an unstoppable force of history. It was a series of choices made by millions of people and Denmark showed that different choices were possible. That is why the story matters. Not because Denmark was perfect, not because every Dne was a hero, but because in the autumn of 1943, when it mattered most, enough people chose decency over obedience.

And that choice saved 7,000 lives. Today, if you visit Denmark, you will find scattered reminders of October 1943. But they are quiet and unassuming, much like the rescue itself. In the fishing village of Gilele, there is a small memorial near the harbor where some of the first boats departed. In Copenhagen, a modest plaque marks the site of the synagogue where Rabbi Melor warned his congregation to flee. The Danish Jewish Museum, designed by architect Daniel Liberskind, tells the story with understated elegance, focusing not on heroism, but on survival and community.

There are no grand monuments, no towering statues of fishermen, no eternal flames. The Danes remember the rescue the way they conducted it, quietly, collectively, and without fanfare. But the absence of spectacle does not diminish the weight of what happened. It amplifies it. Because the lesson of Denmark is not that extraordinary people did extraordinary things. It is that ordinary people when faced with a moral crisis chose to act and their actions proved that goodness is not rare or exceptional.

It is a choice available to anyone at any time. The survivors of the rescue and their descendants carry the story forward in ways both visible and invisible. Many of the 7,000 Jews who escaped to Sweden eventually returned to Denmark and rebuilt their lives, and their families are still there today, woven into the fabric of Danish society. But thousands of others immigrated to Israel, the United States, and elsewhere, carrying with them a story of survival that stands in stark contrast to the horror that consumed the rest of European jewelry.

For these families, Denmark is not just a country. It is a symbol of what humanity is capable of when it refuses to surrender its values to fear. And in Jewish communities around the world, the story of the Danish rescue is taught alongside the stories of the Holocaust. Not as a footnote, but as proof that rescue was possible, that people could have done more and that silence and indifference were choices, not inevitabilities. The Danish rescue does not erase the 6 million who were murdered, but it stands as a rebuke to the excuse that nothing could have been done.

Gayog Duckwitz, the German diplomat who leaked the deportation plan and set the rescue in motion, lived the rest of his life in quiet obscurity. After the war, he returned to Germany and resumed his diplomatic career, eventually serving as West Germany’s ambassador to Denmark in the 1950s. He never sought recognition for what he had done, never wrote a memoir, never gave interviews. It was not until decades later through historical research and survivor testimonies that his role became fully known.

In 1971, Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Memorial, recognized Duckwitz as righteous among the nations, one of the highest honors given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. He accepted the honor with characteristic humility, insisting that he had only done what any decent person would do. But the truth is, most people did not do what Duckwitz did. Most people followed orders, looked the other way, or convinced themselves that someone else would act. Duckwitz made a different choice, and that choice saved thousands.

The fishermen, the students, the ambulance drivers, the priests, and the ordinary Danish citizens who participated in the rescue were never collectively honored in a single ceremony. Never awarded a national medal, never celebrated as the heroes they undeniably were. Many of them died without ever receiving public recognition. But their legacy is not measured in monuments or medals. It is measured in lives. 7,000 people who should have died in the gas chambers of Avitz lived instead. They raised families, built careers, contributed to their communities, and passed down the story of the nation that refused to abandon them.

Their children and grandchildren are walking the earth today because a country of fishermen and shopkeepers decided that decency mattered more than obedience. And in a century defined by genocide, authoritarian brutality, and moral collapse, that decision stands as one of the most important acts of resistance in human history. So why was this story almost erased? Why do most people know about Anne Frank and the Warsaw Ghetto but not about the Danish rescue? The answer is uncomfortable. The story of Denmark does not fit the narrative that the Holocaust was inevitable, that the Nazis were unstoppable, that ordinary people were powerless.

Denmark proves the opposite. It proves that the Holocaust required collaboration, that deportations required compliance, and that rescue was always possible if enough people were willing to act. That truth is inconvenient because it forces us to ask harder questions about the countries that did not act, about the individuals who did nothing, and about the systems that allowed 6 million people to be murdered while the world watched. Denmark did not have more resources, more power, or more time than anyone else.

It simply had more people willing to say no. And that more than any military victory or diplomatic triumph is the legacy that matters. Because the question the Danish rescue forces us to confront is not what they did in 1943. It is what we would do today if faced with the same choice. And whether we are willing to believe that ordinary decency multiplied across thousands of ordinary people can still change the world.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.