“We Want to Marry Cowboys!” — Female German POWs Were Shocked by American Kindness and Life in Texas. NU

“We Want to Marry Cowboys!” — Female German POWs Were Shocked by American Kindness and Life in Texas

Anelise Becca had been told Americans were cold, brutal, and godless. She’d been told Texas was a wasteland of savages and criminals. She’d been told many things during her years working for the German consulate in Mexico City. And every single one of them was proving to be a lie. The lie became obvious the moment the transport truck broke down on a dusty road outside Camp Segoville. The August heat was murderous. 40 women crammed in the back. Guards nervous with rifles.

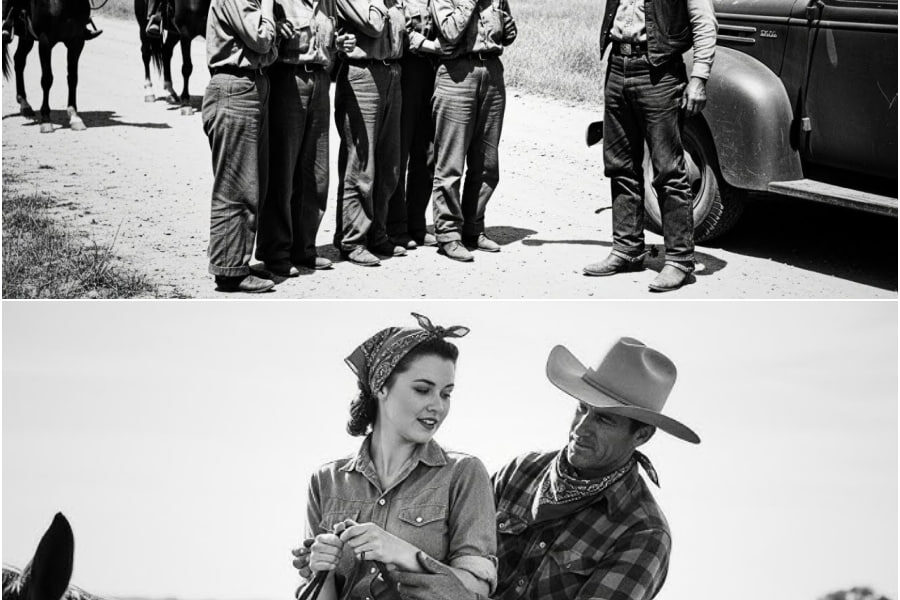

Everyone miserable. Then a pickup truck stopped. Faded blue paint, dented fender, driven by a man in a worn cowboy hat and boots. “Y’all need help?” he called out in a draw so thick and Elisa barely understood. “The guard, young, maybe 22, nodded gratefully.” “Engine overheated. We’re trying to get these prisoners to the camp.” The cowboy looked at the women packed in the truck. His face registered something Analisa hadn’t seen in years. Concern, not suspicion, not hatred, just simple human concern.

That’s no way to transport ladies, he said. German or not, that heat will kill him. I got water in my truck and some shade at my ranch down the road. Let them rest while your engine cools. The guard hesitated. Sir, these are enemy prisoners. They look like hot, thirsty women to me. The cowboy’s voice was firm, but not unkind. Wars almost over anyway. What harm can it do? 20 minutes later, Anaisa stood in the shade of a Texas ranch house, drinking the coldest, sweetest water she’d ever tasted.

The cowboy, he’d introduced himself as Jack Thornton, had set up chairs, brought out ice water, even offered food. My mama would skin me alive if I left ladies suffering in the heat. He explained to the bewildered guard. Analisa watched this man, this enemy treat them with more kindness than her own government ever had. And something inside her chest cracked open. Before we discover what happened next in this remarkable story, tell us where you’re watching from. We love connecting with our global community.

Drop your location in the comments below. Ana Lisa was 31 years old and had spent the last 3 years in various detention facilities. She’d been arrested in Mexico City in 1942, swept up in the mass internment of German nationals. Before that, she’d worked as a translator at the consulate, a quiet job that let her send money back to her family in Bremen. She’d never been political, never cared about Hitler or the Reich. She just wanted to survive, to help her aging parents to live a simple life.

But the war had other plans. Now she sat on a stranger’s porch in Texas, watching a cowboy named Jack the truck’s radiator with competent hands, and she couldn’t reconcile what she was seeing with what she’d been taught. “Is he always like this?” she asked the guard quietly, her English heavily accented, but clear. “Like what?” kind to people he doesn’t know. The guard, his name tag read Morrison shrugged. It’s Texas. People help each other out here. Even Germans, I guess.

We were told Americans hated us. Morrison looked at her for a long moment. Some do, but most folks can separate politics from people. You didn’t bomb Pearl Harbor. You’re just here. Jack returned with a basin of cool water and clean rags. Ladies might want to wash up. It’s a long ride to the camp still. The women stared at him like he’d offered them gold. In the detention center in Mexico, they’d gone days without proper washing. Here was this stranger offering basic dignity like it was nothing.

Why are you being nice to us? The question came from Greta, a younger woman who’d been more defiant than most. We’re your enemies. Jack pushed his hat back and considered the question seriously. Well, miss, way I see it, you didn’t declare war on us. Your government did, and holding a grudge against every German person seems like a waste of good energy. He smiled, weathered face crinkling. Besides, my grandma was German. Came over in 1885, so I guess I’m part enemy, too.

The women laughed, a startled, uncertain sound. When was the last time any of them had laughed? As the truck finally started and they prepared to leave, Jack tipped his hat. Good luck, ladies. Hope they treat you decent at the camp. Analise watched his ranch disappear as they drove away. She’d been in America for 18 months and spent all of it behind fences. This was her first real interaction with an actual American civilian, and he’d been kind. The cognitive dissonance was staggering.

Camp Segoville wasn’t what Anaisa expected. She’d been prepared for brutality, for American efficiency turned cruel. Instead, she found something stranger. Boredom mixed with unexpected comfort. The camp held about 300 German women, most arrested in Latin America like herself. The barracks were clean, if Spartan. The food was adequate, nothing like home cooking, but better than starvation rations. The guards were mostly professional, some even friendly. But it was still a prison. Wire fences, rules, no freedom, just an American version of captivity.

At least they’re not working us to death, said Greta on their first night. She’d been assigned to the same barracks as Anaisa. My cousin was in a labor camp in Poland. She didn’t survive. This is different, agreed Hilda, an older woman from Berlin. They follow the Geneva Convention. We get Red Cross packages, mail, recreation time. We’re still prisoners, Analisa said quietly. True, but there are worse ways to be a prisoner. The camp operated on a system of work details, kitchen duty, laundry, garden maintenance, light manufacturing of non-military goods.

The guard said it was to keep them occupied, to teach useful skills for after the war. Analisa was assigned to the garden detail. That’s where she met more Americans, civilian volunteers from nearby towns who came to help with agricultural projects. Most were older men and women, ranchers and farmers who knew the Texas soil. And that’s where she met Jack Thornton again. “Well, hello,” he said, recognizing her immediately. “The lady from the broken down truck. You made it safe, Mr.

Thornton.” Analisa felt suddenly self-conscious in her work dress. Dirt under her fingernails. What are you doing here? Volunteering. Government asked local ranchers to help teach y’all about Texas crops. I figured I could spare a few hours a week. He surveyed the garden plot. Y’all planning to plant in this heat? The guard said the guard doesn’t know Texas dirt. Jack’s voice was respectful but firm. He turned to the supervising officer. Sir, if you plant now, everything will burn up.

You need to wait for fall planting season, September, maybe October. The guard looked annoyed. We have our schedule. Your schedule doesn’t account for Texas weather, but hey, it’s your garden. Jack tipped his hat and started to leave. Wait. Analisa surprised herself by speaking up. Could you teach us about the seasons here, the soil? Jack turned back, a slow smile spreading. I suppose I could do that. Over the next weeks, Jack became a regular presence at the garden.

He taught them about Texas agriculture, when to plant, how to irrigate, which crops thrived in the heat. But more than that, he talked to them, asked questions, treated them like people, not prisoners. You have family back in Germany? He asked Analise one afternoon while they were testing soil pH. Parents in Bremen. I haven’t heard from them in 2 years. Her throat tightened. I don’t know if they’re alive. I’m sorry. That must be hard. It is what it is.

She focused on the soil sample, avoiding his eyes. What about you? Family. Wife died 5 years ago. Cancer, no kids, just me and the ranch now. I’m sorry. Me, too. He was quiet for a moment. But life goes on. That’s what she would have wanted. There was something in his voice, a loneliness that matched her own. Anelise looked up and found him watching her with an expression she couldn’t quite read. Mr. Thornton. Jack. Just Jack. Jack. She corrected.

Why do you come here? Really? It can’t just be for the gardening. He considered the question seriously. Honestly, I was curious. Wanted to see if y’all were as bad as the propaganda said. Turns out you’re just people. Scared people far from home mostly. didn’t seem right to let you suffer more than necessary. That’s very American of you, he laughed. I’ll take that as a compliment. It was meant as one. Their eyes met. Something passed between them. Not quite attraction, not yet, but recognition.

Two lonely people finding unexpected connection across impossible circumstances. The guard called for work detail to end. As the women filed back to the barracks, Greta fell into step beside Analisa. He likes you, she said in German. Don’t be ridiculous. I’m not. I saw how he looks at you like you’re a person, not a prisoner. Greta grinned. And you like him, too. I barely know him. So, when did knowing someone ever stop feelings from happening? Analisa wanted to argue, but couldn’t because Greta was right.

She did like Jack, liked his quiet competence, his kindness, the way he treated them with dignity when most Americans looked at them with suspicion or hatred. But liking him was dangerous. He was the enemy. She was a prisoner. Whatever she felt, whatever he might feel was impossible. That night, lying in her bunk and Alisa couldn’t stop thinking about Jack’s smile, it was going to be a problem. Jack Thornton started coming to the camp three times a week instead of once.

He brought seeds, tools, advice. He also brought something more precious, normaly. He talked to the women like they were neighbors, not enemies. Asked about their lives before the war, shared stories about his ranch. “You’ve never seen a rodeo?” he asked Analisa one day, shocked. “Well, that’s a tragedy. Rodeo’s the heart of Texas culture. I’ve never even seen a real cowboy until I came here,” she admitted. “I thought they were just in movies. We’re very real.” He gestured at his worn boots and sundamaged hat, though maybe not as glamorous as Hollywood suggests.

“I don’t know. You seem pretty glamorous to me.” The words slipped out before she could stop them. Jack’s eyes widened. Analisa felt her face burn. I mean, the ranch, the lifestyle, it seems glamorous, she stammered in German, then caught herself. Sorry. When I’m nervous, I forget English. Don’t apologize. Jack’s voice was soft. I like hearing you speak German. It’s pretty. They stared at each other. The moment stretched around them. Other women worked in the garden, but they might as well have been alone.

Jack, Analisa whispered. This is We can’t. I know. He looked away, breaking the spell. You’re right. I should probably stop coming here so much. No. She grabbed his arm without thinking. I didn’t mean Please don’t stop coming, Anna. The way he said her name with his Texas draw softening the German syllables made her stomach flip. If I keep coming here, I’m going to do something stupid. Like what? like fall for a woman I can’t have. The honesty was devastating.

Analisa released his arm, her hand trembling. We barely know each other. I know. Doesn’t seem to matter. He met her eyes again. Does it? Before she could answer, Greta called out. Analisa, the guard wants us back inside. The moment shattered. Analisa stepped back, putting safe distance between them. I should go. Yeah, you should. Neither of them moved. Finally, Jack tipped his hat, that familiar, courteous gesture, and walked toward his truck. Analisa watched him go, her heart doing complicated things in her chest.

That evening, the barracks buzzed with gossip. Several women had noticed the exchange between Anaisa and Jack. Some were scandalized, others were envious, a few were calculating. If you can catch an American husband, you’ll never be sent back to Germany,” Hilda said bluntly. “That’s a smart strategy.” “It’s not a strategy,” Analisa protested. “I’m not trying to catch anyone. Maybe you should be.” Hilder’s voice was practical rather than unkind. “Face facts. Germany is destroyed. Most of us have nothing to go back to.

But if we married Americans, we’d have protection, citizenship, a future. You can’t marry someone just for citizenship, Greta objected. Why not? People have married for worse reasons. At least this way you’d be marrying someone kind, someone who treats you well. Hilda gestured around the barracks. Look at us. We’re prisoners of war. When this ends, we’ll be shipped back to a country that’s starving and broken. But if we had American husbands, we could stay, build new lives. The idea spread through the camp like wildfire.

Within days, women were paying extra attention to the civilian volunteers, asking questions, smiling more, learning English phrases. Someone started calling them the cowboy hunters, half mocking, half serious. It’s undignified, complained Fra Vber, one of the older women. Throwing yourselves at American men like desperate girls. We are desperate, someone shot back. and I’d rather be desperate with a future than proud with none. Not all the volunteers were receptive. Some were married, others were old enough to be the women’s fathers.

But a few, the younger bachelors, the widowers like Jack, started lingering longer, talking more, looking at certain prisoners with something other than duty or pity. If this incredible story of unexpected connection across enemy lines is capturing your attention, hit that subscribe button and join our community. These untold stories from World War II reveal the complicated humanity behind the history books. The camp commonant noticed. He called a meeting with the civilian volunteers. Jack came back to the garden the next day looking troubled.

What’s wrong? Analisa asked. Commandant gave us a lecture. Said some of the prisoners are getting too friendly with volunteers, worried about impropriy. He said the word like it tasted bad. Said we need to maintain professional distance. Oh. Analisa felt something sink in her chest. I understand. Do you? Jack’s voice was sharp. Because I don’t. We’re not doing anything wrong. We’re just talking, getting to know each other. What’s improper about that? I’m a prisoner. You’re a civilian volunteer.

There are rules. Stupid rules. He kicked at the dirt. Sorry, I shouldn’t have said that, but it feels wrong. Treating people like they’re dangerous just because of where they were born. That’s war. War’s almost over. This He gestured around the garden, the camp, everything. This is just stubbornness at this point. They worked in silence for a while. Then Jack said quietly, “I’m not going to stop coming here. Not because of some common dance rules, not because people think it’s improper.

I come here because I want to. Because you,” he stopped. “Because I what? Because you make me feel less lonely.” The admission seemed to cost him. “My wife’s been gone 5 years. I thought I was done feeling anything for anyone. Then I met you, and he shook his head. I’m too old to be this foolish. You’re not old. I’m 47. I’m 31. Not exactly young. Young enough. Jack smiled sadly. What are we doing? Anelise. I don’t know.

But I don’t want you to stop coming here either. Even though it’s complicated, especially because it’s complicated. She surprised herself with the honesty. Simple is boring. Complicated is real. He laughed. A real genuine laugh that made her heart lift. You’re something else. You know that. Is that good or bad? Haven’t decided yet. I’ll let you know. They grinned at each other like conspirators. And for a moment, the wire fence and the guard tower and the war itself seemed very far away.

The fall brought cooler weather and new complications. The war in Europe was clearly ending. Everyone could feel it. The question wasn’t if Germany would surrender, but when. And what happened to the prisoners after that? The women divided into factions. Those who wanted to go home to Germany and those who wanted to stay in America. The latter group grew larger every week, fueled by letters from relatives describing the devastation abroad. And encouraged by the growing relationships with American civilians, Analisa received a letter from her cousin in Brmond.

She read it three times, each time hoping the words would change. Braymond is gone. The city you remember doesn’t exist. Allied bombing destroyed most of the old town. Your parents’ house. I’m so sorry, Anaisa. It was hit in a raid last year. They survived but lost everything. They’re living in a shelter now. Conditions are terrible. No food, no medicine. The Soviets are coming from the east. Everyone is terrified. If you have any way to stay in America, do it.

There’s nothing left here for you, only misery and hunger. Save yourself while you can. Analisa showed the letter to Jack during his next visit. He read it silently, his jaw tight. I’m sorry, he said finally. About your parents, about all of it. They’re alive. That’s something. But her voice was hollow. My cousin says to stay here if I can, but how? I’m a prisoner. When the war ends, they’ll ship us back regardless, unless you had a reason to stay.

Their eyes met. The unspoken possibility hung between them like a dangerous promise. Jack, I can’t I won’t use you like that. Analisa’s voice was fierce. If you’re suggesting what I think you’re suggesting, I’m not suggesting anything. I’m just saying there are options, legal options, for prisoners who want to stay. He paused. My friend’s a lawyer. He knows immigration law. Says that if a P marries an American citizen, they can apply for residency after the war. Marriage. The word felt enormous.

It’s just one option. I’m not saying. He ran a hand through his hair. Hell, I don’t know what I’m saying. I just hate seeing you hurt. Seeing all of you hurt. You didn’t start this war, but you’re paying for it anyway. That’s life. doesn’t mean it’s fair. Around them, other women were having similar conversations with other volunteers. The cowboy hunters were getting bolder, asking direct questions about marriage, about sponsorship, about any path to staying in America. Some men fled from the attention.

Others seemed flattered but uncertain. A few, very few, seemed genuinely interested. There’s going to be marriages, Greta predicted one evening. Mark my words, by the time this war ends, at least five women from this camp will have American husbands. What about you? Hilder asked. Interested in catching a cowboy? Maybe. Greta smiled. There’s a volunteer named Tom. He works at the library program. We’ve been talking. He’s kind, funny, lost his wife two years ago. She shrugged. Could be worse.

Could be love. Analisa said quietly. Could be survival. Greta corrected. Same thing really when you think about it. Was it though? Analisa thought about Jack. His slow smile, his rough hands, gentle with plants, the way he looked at her like she mattered. She thought about her destroyed home, her parents in a shelter, her cousin’s advice to save herself. Could you build love from desperation? Could you marry someone because the alternative was death and hope that somewhere along the way survival transformed into something real?

The question kept her awake at night. Jack seemed to be struggling with similar questions. He came to the camp but was quieter now, more reserved, like he was wrestling with something he couldn’t quite voice. Finally, on a gray November afternoon, while they were harvesting the last of the fall vegetables, he said, “Anelisa, I need to ask you something, and I need you to be honest.” Okay. If I asked you to marry me hypothetically, would you say yes because you want to or because you need to?

The question was so direct it stole her breath. I don’t know how to answer that. Try. She set down the basket of vegetables and faced him. If you asked me a month ago, it would have been need. Pure survival. But now, she struggled for words. Now, I don’t know where need ends and want begins. I like you, Jack. I look forward to seeing you. You make me laugh. You make me feel human again. Is that love? I don’t know.

But it’s something, he repeated. That’s honest at least. What about you? If you asked me, would it be out of pity or something more? Not pity. His voice was firm. Never pity. I don’t know what it is exactly. Attraction maybe. Connection. The feeling that I’ve been half alive for 5 years and you make me remember what being fully alive feels like. He looked away. But I’m not sure that’s enough reason to marry someone. No, probably not. They stood in the garden surrounded by dying plants and the promise of winter.

Both grappling with impossible questions. Can I tell you something crazy? Jack asked. Please. Part of me wants to ask you anyway, despite all the logical reasons not to. Despite knowing we barely know each other, despite everything, he met her eyes. Is that insane? Completely? Analisa felt tears prick her eyes. But I’d say yes anyway. Despite all the same reasons, despite knowing we barely know each other, despite everything. So, we’re both insane, apparently. They smiled at each other.

Sad, complicated smiles that acknowledged the impossibility of what they were feeling. I’m not asking, Jack said. Not yet. Not until I’m sure it’s the right thing for both of us. I know, but I’m not ruling it out either. I know that, too. The guard called for work detail to end. As Anaisa walked back to the barracks, she felt something shift inside her. She’d come to America as a prisoner, expecting cruelty. Instead, she’d found kindness, connection, the possibility, however remote, of something like happiness.

Texas wasn’t what she’d expected. Neither were Americans. Neither was Jack Thornton. But maybe that was the point. Maybe the best things in life were the ones you never saw coming. December brought the first frost and a new development that changed everything. The commandant called a mandatory assembly in the main hall. 300 women filed in whispering nervously. Rumors had been flying for weeks about the war ending, about repatriation plans, about their uncertain futures. Ladies, commonant Morrison began. His voice was formal, but not unkind.

I have news from Washington. Germany’s collapse is imminent. Within months, the war in Europe will officially end. At that time, all prisoners of war will be repatriated to their countries of origin. The room erupted. Some women cried in relief. They wanted to go home to find whatever family remained. Others looked stricken. Anelisa felt her stomach drop. However, Morrison continued, raising his voice over the noise. There is an alternative. Any prisoner who has secured sponsorship from an American citizen may apply for a residency permit instead of repatriation.

This requires proof of employment, housing, and financial support. The application process is rigorous and approval is not guaranteed. He paused, surveying the crowd. I’ll be honest, marriage to an American citizen is the most straightforward path to sponsorship. If any of you have formed such relationships with civilian volunteers, now is the time to formalize them. You have until March to submit applications. After that, repatriation will be mandatory for those without approved sponsorship. 3 months. They had 3 months to secure their futures.

After the assembly, the barracks exploded with frantic conversation. Women who’d been casually flirting with volunteers suddenly became deadly serious. Those who’d resisted the idea of cowboy hunting reconsidered in light of the reality. Go home to devastation or find a way to stay. I’m going to ask Tom, Greta announced. Tonight when he comes for library duty, I’m just going to ask him straight out. What if he says no? Hilda asked. Then I go back to Germany and probably die of starvation, but at least I tried.

Greta’s voice was defiant. I’m not going down without a fight. She wasn’t alone. Over the next week, at least a dozen women proposed to their volunteer friends. Some were accepted immediately, others were gently rejected. A few volunteers asked for time to think. Jack didn’t come to the camp for 10 days, and Elise tried not to panic, but every day without seeing him felt like a small death. Had he heard about the deadline and decided to avoid the situation entirely?

Had he realized he didn’t want the complication of a German wife? When he finally appeared, he looked like he hadn’t slept in days. “Can we talk?” he asked. “Privately?” The guard allowed them to walk the perimeter path, still within camp boundaries, but away from the other women. They walked in silence for a while, their breath making clouds in the cold air. I’ve been thinking, Jack finally said, about what Morrison announced, about the deadline, about us. Anelisa’s heart hammered.

and and I talked to my lawyer friend about what marriage to a P would actually mean, the legal process, the scrutiny, the paperwork. He stopped walking and turned to face her. It’s complicated. They’ll investigate to make sure the marriage is legitimate. Interview us separately. Check our stories. If they think it’s a sham marriage just for citizenship, they’ll reject the application and deport you anyway. I see. But here’s the thing. Jack took her hands. the first time he touched her beyond accidental brushes.

I don’t think it would be a sham. I think it would be real. Rushed? Yes. Unconventional? Absolutely. But real. Anaisa couldn’t breathe. Jack, let me finish. I’ve been alone for 5 years. I thought I was done with marriage. Done with feeling anything for anyone. Then you happened. And I know it’s crazy. I know we barely know each other. I know every logical reason this is a terrible idea. He squeezed her hands. But I also know that when I’m with you, I feel alive again.

And when I’m not with you, I spend the whole time wanting to be with you. That has to mean something. It means you’re lonely, Analisa said carefully. And I’m convenient and desperate. No. His voice was sharp. Don’t diminish this. Don’t diminish yourself. You’re not convenient. You’re extraordinary. You’re brave and smart, and you make me laugh even when nothing’s funny. Yes, the circumstances are terrible. Yes, you need help, but that doesn’t mean my feelings aren’t real. Tears were streaming down Anaise’s face now.

I’m scared. Of what? Of using you. Of you regretting this, of building a life on a foundation of desperation and having it collapse when the desperation fades. Jack pulled her closer. What if it doesn’t fade? What if this is the beginning of something good? Weird beginning, granted, but still good. You can’t promise that. No. But I can promise to try. I can promise to treat you with respect. To be faithful to work at this like it matters.

Because it does matter. You matter. He paused. So here’s what I’m asking. Will you marry me? Analisa Becka. Not because you have to. Not because you’re desperate, but because you think maybe, just maybe, we could build something real together. Analisa looked at this man who’d shown her kindness when he didn’t have to, who’d made her laugh during the darkest period of her life, who was offering her not just rescue, but partnership. “Yes,” she whispered. “Yes, I’ll marry you.” Jack kissed her then, gentle and tentative, like he was afraid she might break.

It was the first kiss she’d had in four years, and it felt like coming home to a place she’d never been. Around them, the camp continued its daily routine. But for Analisa and Jack, the world had just shifted into something new and terrifying and full of possibility. The next 3 months were a blur of paperwork, interviews, and bureaucratic nightmares. Jack hired his lawyer friend to navigate the process. Analisa filled out forms until her hand cramped. They were interrogated separately about their relationship.

When they met, what they talked about, intimate details meant to prove the marriage was genuine. What’s her favorite color? The immigration officer asked Jack. Blue, like the sky over the ranch. What does she like to eat? She’s still discovering American food. Says she loves barbecue, but misses German bread. Why do you want to marry her? Jack had looked the officer dead in the eye. Because she makes me happy. Because I respect her. Because I want to spend my life with someone who’s been through hell and still manages to be kind.

Good enough. They’d approved his application. Other women weren’t as lucky. Greta’s application was denied. The immigration board decided her relationship with Tom was insufficiently documented. Tom had only been volunteering for 3 months. They couldn’t prove the relationship was genuine. I’m being sent back, Greta said, her voice hollow. They were packing her belongings the night before her transport. Back to Hamburg. Back to nothing. I’m so sorry, Analisa whispered. Don’t be. You got out. That’s good. Someone should get out.

Greta forced a smile. Take care of that cowboy of yours. Make it worth it for both of us. They hugged, both crying. Analisa watched Greta board the transport truck the next morning, watched it disappear toward the port, and felt survivors guilt crash over her like a wave. Of the 300 women in Camp Segoville, 47 secured sponsorship to stay in America, 22 through marriage, the rest through employment or family connections. 253 were shipped back to Germany. Analisa’s wedding took place on a cold February morning in 1946.

The ceremony was simple, a judge’s office, two witnesses, paperwork that made it legal. She wore a borrowed dress. Jack wore his best suit, the one he’d worn to his first wife’s funeral. Do you, Jack William Thornton, take this woman to be your lawfully wedded wife? I do. And do you, Anelise Maria Becka, take this man to be your lawfully wedded husband? Anaisa thought about her parents in Brmond, about Greta on a ship heading toward uncertainty, about the life she was leaving behind and the life she was choosing.

I do then, by the power vested in me by the state of Texas, I pronounce you husband and wife.” Jack kissed her longer this time, more confident. When they pulled apart, his eyes were bright with unshed tears. “Welcome to Texas, Mrs. Thornton.” The words felt surreal. She was American now, or would be once the citizenship process completed. She was married to a man she’d known for 6 months. She was building a life in a country that had imprisoned her.

It should have felt wrong. Instead, it felt like the first right thing in years. They drove to Jack’s ranch in his pickup truck, the same one that had stopped to help when her transport broke down. The ranch was modest. A small house, a barn, acres of scrub land stretching to the horizon. But it was beautiful in its simplicity. It’s not much, Jack said, suddenly nervous. But it’s paid for, and it’s ours now. I mean, if you want it to be.

Analisa walked through the house. Two bedrooms, a kitchen, a living room with a fireplace, simple furniture, clean but worn. A bachelor’s home, lonely until now. It’s perfect, she said honestly. That night they lay in bed, the first night of many. Jack held her carefully like she might disappear if he gripped too tight. “Are you okay?” he asked. “I’m terrified.” “Me, too. What if we made a mistake? Then we’ll make the best of it.” He kissed her forehead.

We’re in this together now. Whatever happens, Ana curled against his chest and listened to his heartbeat. Outside, Texas stretched into darkness. Somewhere across the ocean, Germany was rebuilding from ashes. And in this small ranch house, two people who’d been enemies were trying to build something neither of them had planned for. It wasn’t the life she’d imagined. But maybe that was okay. Maybe the best lives were the ones you stumbled into when all your plans fell apart. Indeed, 5 years later, Analisa stood in her garden, now flourishing with both Texas crops and German flowers she’d managed to cultivate, and read a letter from Greta.

Dear Analise, I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to write. Life here has been difficult. Hamburg is slowly rebuilding, but progress is painful. I found work at a hospital. They need nurses desperately. The pay is terrible, but at least it’s work. I think about Texas sometimes, about what might have been if my application had been approved. About Tom. I wrote to him once, but never heard back. I don’t blame him. The war is over. He’s moved on.

But here’s the surprising part. I’m not as miserable as I thought I’d be. Germany is home, even broken. My family is here. What’s left of them? And there’s a doctor at the hospital, Carl. He lost his wife in the bombing. We’ve been spending time together. Nothing serious yet, but maybe something. What I’m trying to say is you don’t have to feel guilty about being happy. You made a choice. I made a different one. Both choices were valid.

You got Texas and cowboys and a new life. I got Hamburg and rebuilding and maybe Carl. Different paths, both okay. Be happy, Anelisa. You earned it. Love, Greta. Analisa folded the letter carefully and looked at the ranch house. Through the window, she could see Jack making lunch. In the sideyard, their neighbors children played. They came over most afternoons while their mother worked. And Elisa had started teaching them German, and they taught her to speak English without an accent.

She was American now, officially. The citizenship had come through last year. She could vote, work without restrictions, travel freely. She’d built a life here. Not the life she’d planned in Bremen, but a good life nonetheless. Jack appeared in the doorway. Lunch is ready. You coming? In a minute. She walked over and kissed him, still surprising him after 5 years. I love you. I love you, too. He smiled, weathered, and warm. What brought that on? Just remembering how we got here.

How impossible it all seemed. And now, now it seems inevitable. Like this was always where I was supposed to end up. You believe in fate now? You used to say that was foolish. And maybe I was wrong. Or maybe we make our own fate by choosing to show up every day and try. She took his hand. Either way, I’m glad I chose this. Chose you. Chose Texas. Even though you have to put up with cowboys, especially because of the cowboys, she grinned.

Turns out they’re not so bad. A little rough around the edges, but good hearts underneath. They walked inside together, leaving the garden to grow wild and beautiful in the Texas sun. Years later, when people asked Analise about her journey from prisoner of war to Texas ranch wife, she’d tell them the truth. It wasn’t a fairy tale. It was messy and complicated and built on desperate circumstances, but it was also real. Two people choosing each other when all the logical reasons said they shouldn’t.

Two people building love from unlikely friendship and making it work through sheer stubborn determination. Would you do it again? Someone once asked, knowing how hard it would be. Analisa had looked at Jack, gray now, slower but still steady, and smiled. Every time, she said. I’d choose him every time. And Diane, she meant it. If this story of unexpected love and second chances across impossible circumstances moved you, please share it with others. History isn’t just about battles and politics. It’s about ordinary people making extraordinary choices. Their stories deserve to be remembered.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.