How One Black US Marine Sniper’s “Treetop Perch” Firing Line Made 27 Marksmen Vanish in New Guinea. NU

How One Black US Marine Sniper’s “Treetop Perch” Firing Line Made 27 Marksmen Vanish in New Guinea

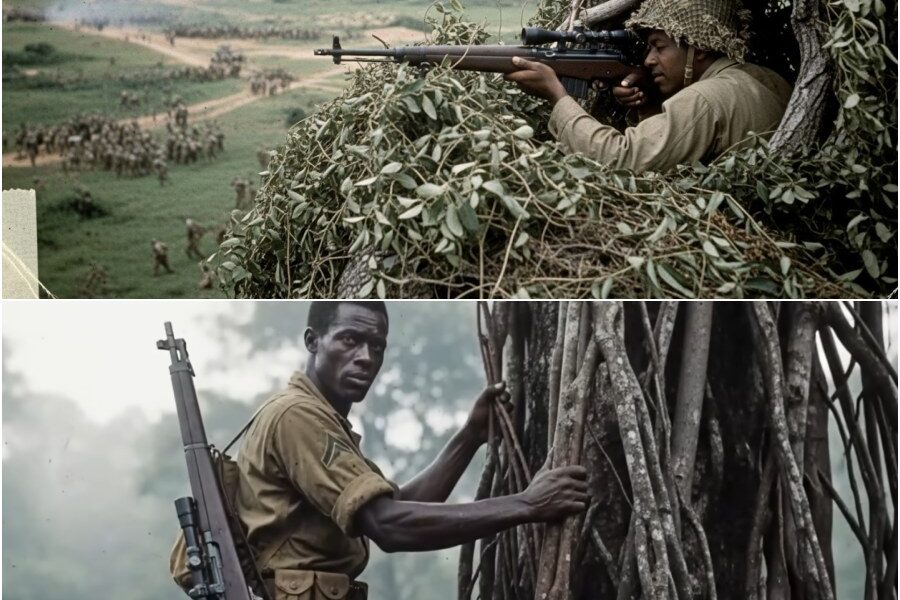

The jungle of New Guinea seemed to swallow sound itself. August 18th, 1943. Sergeant Mitchell Page Jenkins of the First Marine Division peered through the tangle of vines and broad-leafed plants, his breath coming in careful, measured intervals. The humidity pressed against his skin like a hot, wet blanket as sweat trickled down his temples. He could taste the metallic hint of fear at the back of his throat, but his hands remained steady on his Springfield M1903A1 rifle. 300 yd ahead, Japanese snipers had been systematically eliminating anyone who moved along the ridge that led to the American position.

Four Marines had already fallen this morning. “Sir, they’ve got that whole approach zeroed in,” Jenkins whispered to Lieutenant Harold Fitzroy, who crouched beside him. We can’t advance through that killing zone. Not the way command wants us to. The lieutenant’s face hardened. Those are our orders, Jenkins. We move up that ridge in 30 minutes. Jenkins swallowed hard, his eyes scanning the dense canopy across the valley. Standard doctrine called for snipers to operate from concealed ground positions, but something about the angle of fire, the way the Japanese marksmen seemed to disappear after each shot.

Sir, they’re not on the ground, he said, his voice barely audible. They’re in the trees, and that’s where I need to be. Fitzroyy’s eyes narrowed. Absolutely not. Marine snipers operate according to protocol. We don’t climb trees like damn monkeys. Jenkins felt the weight of his decision pressing against his chest harder than his gear. With respect, sir, if we go up that ridge according to protocol, we’ll all be dead by sundown. Before Fitzroy could respond, Jenkins had already begun moving away, heading toward a massive banyan tree that soared nearly 100 ft into the canopy.

“Jenkins,” Fitzroy hissed. “That’s a direct order. You get back here now.” But Sergeant Mitchell Paige Jenkins was already disappearing into the foliage, his rifle slung across his back. As he began to climb, his mind flashed to the firing platforms he’d built as a boy hunting squirrels in rural Mississippi. The memory steadied him as he ascended higher, knowing that his career and the lives of his fellow Marines now hung in the balance of his unauthorized ascent. No one in the First Marine Division knew that one man’s defiance that morning would rewrite battlefield history and save dozens of American lives in the brutal campaign for New Guinea.

Mitchell Paige Jenkins was born on June 30th, 1921 in the small town of Greenwood, Mississippi. The third son of sharecroppers who worked the cottonfields owned by the Patterson family. From an early age, Mitchell’s father, Abraham Jenkins, had taught him to hunt to supplement the family’s meager dinner table. By the time he was 10 years old, young Mitchell could hit a squirrel at 50 yards with his father’s old 22 rifle. ain’t about having the fanciest gun, his father would say.

It’s about knowing where to be and when to be still. Those lessons had crystallized during long days when Mitchell would construct small platforms in the trees, sometimes 15 or 20 ft off the ground, where he’d wait patiently for game to pass below. His older brothers preferred hunting from the ground, but Mitchell found that the elevation gave him a distinct advantage, both in terms of visibility and in keeping his scent above the animals. His childhood wasn’t easy. The Jenkins family faced not only the grinding poverty of depression era Mississippi, but also the harsh realities of racial segregation in the deep south.

School was a luxury that Mitchell could only attend sporadically between harvest seasons, but he devoured books whenever he could get his hands on them. particularly anything about mechanics or engineering. That boy’s got a mind like a steel trap, his mother would proudly tell the neighbors, always figuring out how things work, how to make something better. By his 17th birthday, Mitchell had grown into a tall, lean young man with unusually steady hands and sharp eyes. The local doctor had once commented that Mitchell had the most remarkable visual acuity he’d ever tested, able to read the bottom line of the eye chart from twice the standard distance.

But opportunities for a young black man in Mississippi remained severely limited, and Mitchell knew it. When war came to America on December 7th, 1941, Mitchell was 20 years old and working as a mechanic’s assistant in a garage in Jackson. The owner, Mr. Callaway had recognized Mitchell’s talent for troubleshooting and had taken a risk hiring him despite complaints from some white customers. The day after Pearl Harbor, Mitchell stood in line at the recruitment office, only to be told that the Marine Corps did not accept colored applicants.

The policy stung, but it wasn’t surprising. He enlisted in the Army instead, where he was assigned to a segregated support unit. He had no idea that soon a presidential order would change everything, and those hunting skills learned in Mississippi trees would soon become the difference between life and death for dozens of men. In June 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry and government. While this didn’t immediately integrate the armed forces, it did create pressure for all branches to begin accepting black recruits.

Later that summer, the Marine Corps reluctantly began accepting its first black Marines, though they were trained separately at Montford Point Camp, a segregated facility near Camp Lun in North Carolina. Jenkins, still in the army, but having demonstrated exceptional marksmanship, applied for transfer as soon as he heard that the Marine Corps had opened its doors. His shooting scores had caught the attention of several officers, and with the war intensifying in the Pacific, the need for skilled marksmen outweighed other considerations.

His transfer was approved in November 1942. At Montford Point, Jenkins and other black recruits faced grueling training and persistent discrimination. Drill instructors pushed them beyond normal limits, seemingly intent on proving that they couldn’t measure up to white marines. Facilities were substandard and liberty restrictions were more severe than for white trainees at nearby Camp Lune. “They expect us to fail,” Jenkins told his bunkmate one night after a particularly brutal day of training. “But that just means we’ve got to be twice as good.” And Jenkins was good, especially on the rifle range.

During qualification, he shot a perfect score, something only three other trainees in the entire camp had managed that month. The range officer, a crusty gunnery sergeant named McGrder, had stared at Jenkins target in disbelief. “Where’d you learn to shoot like that, recruit?” he demanded. “Squirrels, sir,” Jenkins had replied. “Mississippi squirrels are mighty small targets.” McGrder had almost smiled. “Almost.” “Well, the Japanese are bigger than squirrels, but they shoot back. Remember that.” Jenkins exceptional marksmanship earned him additional training.

While most of the Montford Point Marines were being assigned to defense battalions or ammunition companies, segregated units typically kept away from frontline combat. Jenkins was selected for specialized sniper training, a rarity for black marines at the time. The sniper instructor, a battleh hardardened lieutenant named Harrington, who’d fought at Guadal Canal, approached training with a cold pragmatism that transcended race. I don’t care if you’re purple with yellow polka dots, he told Jenkins on the first day. If you can put rounds on target, you’ll save marine lives.

That’s all that matters to me. During those 8 weeks of intensive training, Jenkins absorbed everything. Calculating windage and elevation, reading terrain, camouflage techniques, and patient observation. But he never mentioned his childhood tree platforms. Marine snipers operated according to doctrine, which meant shooting from concealed positions on the ground. His unorthodox ideas would have been dismissed immediately. When he finally shipped out to join the First Marine Division in the South Pacific in early 1943, Jenkins was one of fewer than 20 black Marines who had completed sniper training.

He had earned his sergeant stripes, but he knew that in the eyes of many, he still had something to prove. As he boarded the transport ship in San Diego, an officer stopped him. “Sergeant Jenkins,” the captain said, reviewing his papers. “Says here you qualified expert on every weapon they put in your hands.” “Yes, sir,” Jenkins replied, standing at attention. “Good. Where we’re going, we’re going to need every marksman we can get.” The captain handed back his papers.

“The Japanese in New Guinea. They’re like ghosts in those jungles. Here one minute, gone the next.” Jenkins nodded, thinking of the Mississippi woods of his youth. Sir, ghosts still bleed when you find them. He had no inkling, then that his greatest test would come not from the enemy, but from the rigid military doctrine that failed to account for the unique challenges of jungle warfare. Nor could he have known that soon those skills honed hunting from treetops would be all that stood between life and annihilation for his fellow Marines.

By mid 1943, the Pacific War had reached a critical juncture. The strategic island hopping campaign designed to push toward Japan had brought Allied forces to New Guinea, a massive island just north of Australia. Its dense jungles, sweltering climate, and mountainous terrain made it one of the most challenging battlefields of the war. disease claimed almost as many casualties as enemy fire with malaria, deni fever, and dissentry sweeping through units with devastating effect. The Japanese had built extensive defensive positions throughout the island, particularly around key airfields and harbors.

Unlike the open beaches of some Pacific islands, New Guiney’s thick jungle canopy provided perfect cover for snipers and hidden machine gun nests. Conventional tactics often proved ineffective in this environment, where visibility rarely extended beyond 50 yards, and maps were woefully inadequate for the complex terrain. For the Americans, taking New Guinea was essential to General MacArthur’s strategy of approaching Japan through the Philippines. I shall return. He had famously promised after being forced to evacuate the Philippines in 1942.

New Guinea was a critical stepping stone toward fulfilling that promise. The First Marine Division had already earned legendary status after their brutal fight on Guadal Canal. But New Guinea presented entirely different challenges. The division landed along the northeastern coast in July 1943. tasked with securing strategic points that would allow further advances toward Japanese strongholds. Intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese 28th Infantry Division had fortified a series of ridges overlooking the coastal approaches. These veteran Japanese troops had been fighting in jungle conditions for years and had perfected the art of camouflage and ambush.

They were dug in, determined, and dangerous, especially their snipers, who had developed tactics specifically adapted to the jungle environment. What American commanders failed to fully appreciate was how the Japanese snipers had adapted to jungle fighting. Standard American doctrine taught in every sniper school emphasized concealed ground positions with good fields of fire. But the dense undergrowth of New Guinea limited visibility from the ground, forcing adaptations that weren’t in any field manual. By the time Sergeant Jenkins and his unit moved into position near the Torichelli Mountains on August 15th, 1943, the campaign had already claimed hundreds of American lives.

The First Marine Division was ordered to secure a series of ridges that would provide access to Japanese airfields further inland. What should have been a straightforward advance had turned into a nightmare of hidden enemies and devastating ambushes. Colonel Lewis Puller, the legendary Chesty Puller, who commanded the First Regiment, had gathered his officers for a briefing the night before Jenkins fateful decision. Gentlemen, Puller said, his face illuminated by a shielded lamp in the command tent. Our intelligence indicates approximately 200 Japanese defenders dug into these ridges.

He pointed to a map spread on a makeshift table. They’re well supplied, well positioned, and they’ve had months to prepare, but we’re Marines, and we’re going to take that ground. Lieutenant Fitzroy had raised his hand. Sir, we’ve lost 17 men to snipers in the past 3 days, all along the same approach. Request permission to send a recon team to locate those firing positions before we advance. Puller had considered this for a moment. Request denied. Lieutenant, we don’t have time.

Command wants that ridge secure by tomorrow evening. You’ll advance as planned at 0900 hours. The orders were clear. advance up the ridge using standard fire and maneuver tactics with three platoon moving in coordinated bounds while supporting fire from machine guns suppressed enemy positions. It was textbook Marine Corps doctrine proven effective on dozens of battlefields. But New Guinea wasn’t a textbook battlefield, and the Japanese defenders weren’t fighting by any book the Marines had studied. What the Americans didn’t know was that the Japanese force they faced wasn’t the 200 defenders intelligence had estimated, but closer to 350, including a specialized group of 35 snipers who had been specifically trained for jungle operations.

These marksmen had developed a tactic rarely seen before. They operated from carefully constructed platforms high in the jungle canopy where they had superior visibility while remaining virtually invisible from below. From these elevated positions, they could observe American movements across the ridge approaches and deliver devastating fire from unexpected angles. Conventional counter sniper tactics were useless against an enemy no one thought to look for in the treetops. The night before the planned assault, Jenkins had listened intently as Lieutenant Fitzroy briefed the platoon on the next day’s operation.

“We move at 0900 hours. Three squads advancing in sequence with covering fire from the 30th machine gun company,” Fitzroy explained, pointing to a rough sketch of the terrain. “Intelligence believes there are Japanese snipers in these areas.” He circled several spots on the map. “Keep your eyes open and your heads down.” Private First Class Ramon Diaz, a replacement who had joined the unit just two weeks earlier, raised his hand. “Sir, how are we supposed to spot snipers in this jungle?

You can barely see 20 yards in any direction.” “You don’t spot them, private,” Fitzroy replied grimly. “You spot their muzzle flash if you’re lucky. Otherwise, you just keep moving and trust your buddies on the flanks to get them before they get you.” Jenkins had remained silent during the briefing, but as the men dispersed to prepare their gear, he approached Lieutenant Fitzroy privately. “Sir,” he began carefully. “I’ve been studying the pattern of fire from those snipers. Something doesn’t add up.” Fitzroy looked up from his map, “What do you mean, Sergeant?

The angles, sir. I’ve been watching where our men get hit. The rounds are coming in at a downward trajectory, steeper than you’d expect from someone firing from ground level. even accounting for the slope. The lieutenant frowned. What are you suggesting? I think they’re above us, sir. In the trees. That’s why we can’t spot them, and that’s why our counter fire isn’t effective. Fitzroy had dismissed the idea with a wave of his hand. That’s not how snipers operate, Sergeant.

The Japanese follow the same basic tactical doctrine we do. Tree shooting is unstable and limits mobility. No trained marksman would choose that position. Jenkins wanted to argue, but knew it would be futile. Military doctrine was treated as gospel, and suggesting alternatives, especially coming from one of the few black non-commissioned officers in the division, would likely be seen as presumptuous. Instead, he had simply nodded. “Yes, sir, just a thought.” “Stick to the plan, Jenkins,” Fitzroy had said. “We advance at 0900.” That night, as rain pounded the jungle canopy and dripped through to the marines huddled below, Jenkins lay awake, turning the problem over in his mind.

He thought of his childhood days in Mississippi, of the perfect stillness he’d achieved in his tree platforms, of the different perspective that height provided. By dawn he had made his decision, though he knew it might cost him his stripes, or worse. As the first hint of daylight filtered through the dense foliage on August 18th, 1943, the Marines of Second Platoon prepared for their advance. The ridge before them seemed quiet, almost peaceful in the early morning light. Birds called from the canopy, and insects buzzed incessantly around the men’s sweat- soaked uniforms.

Jenkins checked his Springfield rifle one last time, ensuring the scope was properly secured and the action was clean despite the omnipresent jungle moisture. Next to him, PFC Diaz fidgeted nervously with his M1 Garand. First time in the real thing? Jenkins asked quietly. Diaz nodded, his young face tense. Trained for beaches and open country. Nobody said anything about fighting ghosts in a green hell. Jenkins studied the young Marine. Diaz couldn’t have been more than 19 years old. With a thin mustache that looked like it had just recently filled in, he had a picture of a pretty dark-haired girl tucked in his helmet band.

A sister, girlfriend, or wife? Jenkins didn’t know. Listen, Jenkins said, “Stay low. Move when the sergeant tells you and watch the trees.” “The trees?” Diaz looked confused. “Just trust me. Don’t just scan the ground. Look up.” Lieutenant Fitzroy moved among the men, checking equipment and offering lastminute instructions. When he reached Jenkins, he paused. Your job is to spot and eliminate any snipers targeting our advance, Sergeant. Standard counter sniper protocol. Understood. Yes, sir. Jenkins replied, knowing already that he would be disregarding that order as soon as the lieutenant moved out of sight.

At precisely 0900 hours, the first squad began moving up the ridge, using the sparse cover provided by rocks and vegetation. Jenkins hung back, watching intently for any sign of enemy activity. For 5 minutes the advance continued without incident. Then suddenly a shot rang out, followed quickly by another. Two Marines went down, one clutching his throat, the other hit in the center of his chest. “Sniper!” someone shouted and the Marines dove for cover, returning fire blindly into the jungle.

Lieutenant Fitzroy crawled to Jenkins position. Can you see where it’s coming from? Jenkins scanned the opposite treeine, looking not at the ground, but up into the canopy. For a moment, he thought he caught a glimpse of something, a slight movement about 60 ft up in a large banyan tree. I think so, sir, but I need a better vantage point. Before Fitzroy could respond, three more shots cracked through the humid air, and another marine fell. The Japanese snipers were picking them off with methodical precision, seemingly immune to the return fire being directed at ground level.

It was at that moment that Jenkins made his fateful decision, slipping away from the main unit and heading toward a massive banyan tree that stood behind their position. As he began his unauthorized climb, he knew he was violating direct orders and established doctrine. If he survived, he might face a court marshal. If his hunch was wrong, he’d be abandoning his unit during combat, one of the most serious offenses in military law. But something deep in his gut told him he was right.

And if he was, the lives of dozens of Marines hung in the balance. The climb was arduous, made more difficult by the need to keep his rifle from snagging on branches and vines. Jenkins moved carefully, testing each handhold before committing his weight. The Banyan’s extensive aerial root system provided natural handholds, and years of climbing Mississippi oaks and hickories had taught him how to distribute his weight effectively. 50 ft up he found what he was looking for. A natural platform formed by several large converging branches, partially concealed by foliage, but offering a commanding view of the ridge and the opposing jungle.

He settled into position, wiping sweat from his eyes, and carefully unslung his rifle. Through his scope, the battlefield took on an entirely different aspect. What had seemed like an impenetrable wall of vegetation from ground level now revealed subtle patterns and openings. Jenkins methodically scanned the canopy of the forest across the ridge, looking for any irregularity that might indicate a human presence. There, about 60° to his right, approximately 300 yd away, something didn’t match the natural patterns of the foliage.

Jenkins adjusted his scope, focusing carefully. A platform similar to his own had been constructed, where several branches of a large tree intersected, partially hidden by strategically placed foliage, and on that platform lay a Japanese sniper, his rifle trained on the ridge where American marines were still pinned down. Jenkins took a deep breath, calculating distance, wind, and the slight drop that gravity would impose on his bullet over that range. He exhaled slowly, then held, squeezing the trigger with deliberate pressure.

The rifle kicked against his shoulder, the report echoing through the canopy. Through his scope, he saw the Japanese sniper jerk once, then go still. One down. Jenkins shifted position slightly, scanning for additional targets. Now that he knew what to look for, other platforms became visible to his trained eye. There, 70 yards to the left of his first target, another sniper nest. And beyond that, another. The Japanese had created an interlocking field of fire from the canopy, invisible to anyone operating according to standard groundbased tactics.

For the next 20 minutes, Jenkins worked methodically, identifying and eliminating Japanese snipers one by one. Each shot required careful calculation and perfect execution. Between shots, he would change his position slightly on the platform to avoid giving away his location from muzzle flash or movement. On the ground, the Marines of Second Platoon were initially confused by the sound of a rifle firing from behind and above them. “Lieutenant Fitzroy scanned the area, trying to locate the source of the shooting.

“Is that one of ours?” he asked the radio operator beside him. “I think it’s Jenkins, sir,” the radio man replied. I saw him heading toward that big tree behind us about 20 minutes ago. Fitzroyy’s face darkened with anger. Damn it, he’s disobeyed a direct order. But before he could say more, they noticed something remarkable. The deadly, accurate Japanese sniper fire that had pinned them down was diminishing. One by one, the enemy firing positions were falling silent. PFC DS, who had been hugging the ground beside a fallen log, raised his head cautiously.

Sir, I think whatever Jenkins is doing, it’s working. The japs are dropping like flies. Fitzroy watched in disbelief as the situation transformed. After 10 minutes, without taking any casualties, he made a decision. First squad, prepare to advance, he ordered. Second squad, covering fire. The Marines moved forward cautiously at first, then with growing confidence as they realized the Japanese snipers who had terrorized them were being systematically eliminated. From his elevated position, Jenkins continued his methodical work, identifying and neutralizing one enemy position after another.

2 hours into the operation, Jenkins had confirmed 17 enemy snipers eliminated. His position in the canopy gave him the same advantage the Japanese had been exploiting, but with one crucial difference. Jenkins was a better shot. His childhood experiences had taught him how to maintain perfect stillness on an elevated platform. How to account for the different ballistics of shooting from height and how to remain invisible among the foliage. The tide of battle had turned completely. What had begun as a potentially devastating ambush had transformed into an American advance.

Lieutenant Fitzroyy’s platoon, followed by the rest of the company, pushed forward and secured the ridge by mid-after afternoon, suffering only minimal additional casualties. As the Marines consolidated their position, Jenkins remained in his tree, continuing to scan for threats. Around 1,600 hours, movement caught his eye. A group of approximately 10 Japanese soldiers attempting to flank the American position from the east using a draw that wasn’t visible from the ridge. Jenkins keyed the small radio he carried. Sierra one to blue leader.

Enemy movement your east flank. Draw at coordinates tango 7. Approximately one squad strength moving toward your position. Fitzroyy’s voice crackled back. Copy Sierra 1. Can you engage? Affirmative. Jenkins replied, already adjusting his aim. The Japanese soldiers, moving in single file through the undergrowth, had no idea they were under observation. Jenkins began engaging the last man in the formation, then worked his way forward. By the time the Japanese realized they were under fire, five of their number had fallen.

The others scattered, but Jenkins elevated position gave him a decisive advantage. Within minutes, the entire enemy squad had been neutralized. By sunset, when Jenkins finally descended from his perch, the confirmed count of enemy soldiers he had eliminated stood at 27, most of them snipers, who had been using the same elevated tactics he had adopted. As he approached the command position established on the ridge, Jenkins braced himself for the reprimand he expected. Lieutenant Fitzroy stood waiting, his expression unreadable.

Sergeant Jenkins reporting, sir,” he said, coming to attention despite his exhaustion. Fitzroy was silent for a long moment. Finally, he spoke. “You disobeyed a direct order, Sergeant.” “Yes, sir, I did. You abandoned your assigned position without authorization.” “Yes, sir.” Fitzroyy’s stern expression suddenly broke into a tired smile. “And you saved this entire operation. 27 confirmed kills, Jenkins. the most effective counter sniper action I’ve ever witnessed. Jenkins remained at attention, uncertain how to respond. “At ease, Sergeant” Fitzroy said.

“Colon Puller wants to see you, and for what it’s worth, I’m recommending you for a Silver Star.” The meeting with Colonel Puller was brief, but consequential. The legendary Marine officer listened intently, as Jenkins explained his reasoning, and described the Japanese sniper tactics he had observed. So, you figured they were in the trees because of the angle of fire? Puller asked. Yes, sir. And because we couldn’t spot them despite clear fields of fire, they had to be above our line of sight.

Puller nodded thoughtfully. And you learned this tree climbing business hunting squirrels in Mississippi. Yes, sir. My father taught me. Said, if you want to hunt something that lives in the trees, sometimes you need to go where they are. Simple wisdom, Puller remarked. Sometimes the best tactical innovations come from outside the manual. He studied Jenkins for a moment. You realize that technically I should have you court marshaled for disobeying a direct order in combat? I understand that, sir.

Puller waved a hand dismissively. But I’m not going to do that. Instead, I want you to train a dozen other snipers in these techniques. We’ve been fighting the Japanese on their terms. It’s time we adapted. Sir, Jenkins was stunned. You heard me, Sergeant. Starting tomorrow, you’re going to create a special sniper section, elevated firing platforms, counter sniper operations, the works. Lieutenant Fitzroy will assist you with whatever you need. Yes, sir. Thank you, sir. As Jenkins turned to leave, Puller added, “One more thing, Jenkins.

Sir, the official report will state that you were operating under orders to test an experimental tactical approach. understood. Jenkins understood perfectly. The Marine Corps wasn’t ready to officially acknowledge that a black sergeant had innovated a tactic that contradicted established doctrine. Understood, sir. The ripple effects of Jenkins actions spread quickly through the First Marine Division. Within days, he had established a training program for selected marksmen, teaching them the techniques of canopy combat. The treeine snipers, as they became unofficially known, adopted Jenkins methods with enthusiasm.

PFC Diaz was among the first volunteers. If Jenkins can do it, I can learn it. He told his buddies, “Man saved my life up there on that ridge.” The impact on subsequent operations was dramatic. Japanese snipers accustomed to operating with impunity from their elevated positions suddenly found themselves vulnerable to American marksmen using the same tactics but with superior marksmanship. Casualty rates among advancing Marine units dropped significantly and the psychological advantage shifted. A Japanese prisoner captured in late September 1943 revealed the impact on enemy morale.

Through an interpreter, he explained, “We thought Americans could not see us in the trees. Then suddenly our snipers began dying. We called it death from above. Many became afraid to use the platforms. By October, the treetop perch technique, as it was documented in unofficial field reports, had become standard procedure for marine sniper operations in jungle environments. Jenkins continued to lead from the front, participating in operations throughout the New Guinea campaign and accumulating a total of 49 confirmed enemy eliminations, all from elevated positions.

The official Marine Corps histories would later describe these tactics clinically, adapted firing positions to counter specific Japanese sniper deployments in arboral settings. But the Marines who fought in those jungles knew the truth. It was Mitchell Jenkins, a black sergeant from Mississippi, who had changed the equation by daring to challenge doctrine when reality demanded it. Lieutenant Fitzroy, who had initially resisted Jenkins approach, became one of his strongest advocates. In a letter to his wife dated November 12th, 1943, he wrote, “We have a sergeant in our unit, a colored fellow named Jenkins, who has saved more Marine lives than anyone I’ve encountered in this war.

He changed the way we fight in these jungles, climbing trees like he was born to it, teaching others to do the same. Without him, I doubt I’d be writing this letter now. Funny how the man I nearly caught marshaled for disobedience has become someone I’d follow into hell itself. For Jenkins, the validation of his approach brought a quiet satisfaction. He wasn’t seeking recognition. He was simply applying the practical knowledge his father had taught him years earlier in the woods of Mississippi.

When a war correspondent tried to interview him about his innovations, Jenkins deflected. Just doing what needed doing him, he told the journalist. Nothing special about climbing a tree if that’s where you need to be. The war in the Pacific ground on. After New Guinea came campaigns in the Philippines, Pleu and ultimately Okinawa. Jenkins served through them all, his reputation growing among those who knew, but remaining largely unrecognized in official records. His techniques, however, became standard training for marine snipers operating in jungle environments.

When the war ended in August 1945, Sergeant Mitchell Page Jenkins returned to Mississippi with a collection of medals, including the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart, but little public recognition. Like many black veterans, he found that the country he had fought for still denied him basic rights and opportunities. He used his GI Bill benefits to study mechanical engineering, eventually finding work with an automotive manufacturer in Detroit. He married Eloise Washington, a school teacher he had corresponded with during the war, and they raised three children in a modest home on Detroit’s west side.

Jenkins rarely spoke about the war. His oldest son, Abraham, named after Jenkins father, later recalled, “Dad never talked about what he did in the Pacific. We knew he had medals in a box in his dresser drawer, but he never displayed them or bragged. It wasn’t until his funeral that we heard from other Marines what he had really done.” In military circles, however, Jenkins innovation lived on. The Marine Corps Sniper School at Quantico incorporated elevated firing position techniques into its curriculum by the 1950s, though the origin of these tactics was attributed simply to Pacific theater experience.

During the Vietnam War, when American forces again faced jungle combat, the treeine tactic was rediscovered and deployed, saving countless American lives. In 1972, nearly three decades after his actions in New Guinea, Jenkins received an unexpected letter from the Marine Corps Sniper School at Quantico. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Davidson, the commanding officer, had been researching the origins of elevated sniper tactics and had uncovered Jenkins role. The letter read in part, “Dear Mr. Jenkins, it has come to our attention through declassified action reports that you were the originator of what we now teach as elevated deployment tactics to all our sniper students.

Your innovations in New Guinea have become a cornerstone of modern sniper doctrine. We would be honored if you would consider visiting our facility to speak with our instructors and students about your experiences. Jenkins, then 51 years old and supervising an assembly line at Ford, initially declined, but his wife persuaded him that it was important for the full story to be told. In May 1972, he visited Quantico, where he was received with honors that had been long delayed.

A young sniper instructor after hearing Jenkins describe his improvised platform in the Banyan Tree asked why he had risked his career by disobeying orders. Jenkins thought for a moment before answering. Sometimes the rule book doesn’t match what’s in front of your eyes. When that happens, you have to trust what you see, not what you’ve been told. The Japanese were killing my brothers from the trees, so that’s where I needed to be to stop them. Mitchell Page Jenkins passed away in 1989 at the age of 68.

His obituary in the Detroit Free Press made only passing mention of his military service, noting that he was a decorated marine who served in the Pacific. Like so many of his generation, his extraordinary courage and innovation remained largely unheralded in public memory. But in the specialized world of military snipers, his legacy endured. Today, elevated firing positions are standard doctrine for sniper operations in wooded terrain worldwide. At the Marine Corps Sniper School, instructors still occasionally refer to certain techniques as the Jenkins position, though few now remember the origin of the name.

In 2012, military historian Dr. Elellanena Westfield published Invisible Innovations: Forgotten Tactical Developments of World War II, which included a chapter on Jenkins and his tree platform techniques. Through interviews with surviving Marines who had served with him and a thorough review of afteraction reports, Westfield pieced together the full story of how one man’s willingness to challenge doctrine had changed the course of jungle warfare. What makes Jenkins story so remarkable, Westfield wrote, is not just the effectiveness of his innovation, but the moral courage it required.

Facing both the institutional resistance to new ideas and the racial barriers of his time, Jenkins chose to act on his conviction that there was a better way to protect his fellow Marines. In doing so, he demonstrated that true military genius often comes not from rigid adherence to doctrine, but from the ability to adapt when circumstances demand it. In a letter discovered among Jenkins effects after his death, Lieutenant Fitzroy, who had maintained correspondence with him for decades after the war, perhaps summed it up best.

History may not remember what you did that day in New Guinea, Mitch, but those of us who were there will never forget. You taught us that sometimes courage means knowing when to break the rules and that wisdom can come from unexpected places. I’ve often wondered how many young men came home to their families because you had the courage to climb that tree when everyone else said to stay on the ground. In the decades since World War II, the United States Marine Corps has evolved significantly in both tactics and composition.

Racial integration of the armed forces, officially ordered by President Truman in 1948, gradually transformed the military from segregated units to a more unified fighting force. The contributions of black Marines like Mitchell Jenkins, once obscured by the prejudices of the time, have slowly gained recognition through the determined efforts of historians and fellow veterans. At the National Museum of the Marine Corps near Quantico, Virginia, a small display added in 2015 finally acknowledges the treetop tactics pioneered in the Pacific campaign with a photograph of Jenkins and a brief description of his innovation.

It’s a modest recognition for an action that saved dozens, perhaps hundreds of American lives. Dr. James Hrix, Jenkins’s grandson, who serves as a professor of military history at Howard University, has worked to ensure his grandfather’s contributions aren’t forgotten. “What’s remarkable about my grandfather’s story isn’t just what he did, but when he did it,” Hris explained in a recent interview. “This was 1943. The military was still segregated. Black Marines were still fighting for basic respect, let alone recognition for tactical innovations.

Yet in that moment of crisis, when lives were on the line, he chose to act on what he knew was right, regardless of the potential consequences to his career. The treetop perch technique pioneered by Jenkins, has evolved into what modern military doctrine calls elevated firing platform deployment, now a standard part of sniper training for jungle and forested environments. The core insight that sometimes the best way to counter an enemy is to adopt and improve upon their own tactics remains as valid today as it was in the jungles of New Guinea.

Former Master Sergeant Raymond Diaz, who passed away in 2010 at the age of 86, was perhaps the last surviving Marine who had trained directly under Jenkins in 1943. In an oral history recorded for the Veterans History Project in 2005, Diaz recalled the impact Jenkins had made on him as a young Marine. I was just a scared 19-year-old kid from the Bronx. Diaz remembered, never seen jungle before, never been shot at. Jenkins took me under his wing, taught me how to move, how to see, how to stay alive.

When he started climbing trees to get those Japanese snipers, we thought he was crazy. Then we saw it working and suddenly we all wanted to learn. Diaz paused, his eyes distant with memory. You know what the ironic thing was? Back home, this black man from Mississippi couldn’t drink from the same water fountain as me in some states. But out there in that green hell, he was the one teaching us how to survive. War has a way of stripping away the nonsense and showing what really matters.

The tactical innovation Jenkins introduced emerged from a unique confluence of personal experience and battlefield necessity. His childhood hunting techniques developed for practical survival in rural Mississippi proved perfectly adapted to the challenges of jungle warfare. It was a powerful reminder that effective military innovation doesn’t always come from training manuals or established doctrine, but often from the diverse lived experiences that individual service members bring to the battlefield. Jenkins never sought recognition for his actions. In the few interviews he gave late in his life, he consistently emphasized that he was simply doing what needed to be done to protect his fellow Marines.

I didn’t climb that tree to make history, he told a military historian in 1987, 2 years before his death. I climbed it because that’s where I could see the enemy. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the hardest to see when you’re trained to look in only one direction. This perspective, the willingness to look beyond established doctrine when circumstances demand it, represents one of the most valuable lessons from Jenkins story. Military organizations with their necessary emphasis on discipline and standardized procedures sometimes struggle to adapt quickly to unexpected challenges.

It often falls to individual service members, drawing on their unique backgrounds and insights to bridge the gap between doctrine and reality. Colonel Marcus Harrison, a former sniper instructor at Quantico, who later researched Jenkins techniques for modern applications, observed, “What Jenkins did wasn’t just effective tactically. It represented a fundamentally different way of thinking about the problem. Instead of trying to fight the Japanese according to our doctrine, he recognized the value in their approach, then improved upon it using his own experience.” That kind of adaptive thinking is what we try to cultivate in today’s Marines.

The 27 enemy marksmen Jenkins eliminated on August 18th, 1943 represent only the most immediate impact of his innovation. The true measure of his contribution lies in the countless Marines whose lives were saved as his techniques spread throughout the Pacific theater. By the campaign’s end, elevated sniper positions had become standard practice, dramatically reducing casualties from the hidden Japanese marksmen who had previously terrorized advancing troops. A declassified afteraction report from the Philippines campaign in 1944 noted, “Implementation of elevated counter sniper tactics has reduced casualties from enemy marksmen by an estimated 65% compared to previous operations.

Though the report didn’t mention Jenkins by name, it was his improvisation that had catalyzed this shift in approach. For the Japanese forces, the sudden American adoption of their own tactics created a significant psychological impact. A captured Japanese officer’s diary found during the Ley campaign contained this telling entry. The Americans have learned to fight like ghosts in the trees. Our snipers no longer feel safe. The hunters have become the hunted. Perhaps the most poignant testimony to Jenin’s impact came in the form of letters he received decades after the war.

In the 1970s and 80s, as veterans organizations helped former Marines reconnect, Jenkins began receiving correspondents from men who had served in the Pacific theater. “You wouldn’t remember me,” one letter began. “But I was a replacement who joined Fox Company in November 43.” The first thing our sergeant told us was to learn the Jenkins method if we wanted to stay alive in sniper country. I made it home to my family because of what you taught those who taught me.

Thank you isn’t enough, but it’s all I have to offer. Another wrote simply. I have three children and seven grandchildren who wouldn’t exist if not for what you did in those jungles. God bless you, Sergeant Jenkins. These personal acknowledgements meant more to Jenkins than any official recognition. As his wife, Eloise, later recalled, “Those letters would make him cry. Mitchell wasn’t a man who cried easily, but hearing from those boys, men by then with grown children of their own, it touched something deep in him.” In his final years, Jenkins occasionally spoke to school groups in Detroit, about his wartime experiences, though he always downplayed his own role.

He emphasized instead the importance of thinking independently and having the courage to act on one’s convictions even when they ran counter to established authority. Sometimes the right thing to do isn’t the thing you’re told to do. He would tell the students. You have to look with your own eyes and think with your own mind. That’s true whether you’re in a war or just living your everyday life. When Mitchell Page Jenkins was laid to rest with military honors at Great Lakes National Cemetery in Holly, Michigan in 1989, his funeral was attended not only by family and local friends, but by several aging Marines who had traveled from across the country to pay their respects.

Among them was former Lieutenant Harold Fitzroy, then in his 70s, who placed his own Silver Star on Jenkins casket. He earned this more than I ever did, Fitzroy told Jenkins widow. I just followed the rule book. Mitch had the courage to write a new one when it mattered most. The story of Sergeant Mitchell Page Jenkins and his treetop perch innovation illustrates a timeless truth about warfare and human ingenuity. In the chaos and complexity of combat, victory often depends not on rigid adherence to established doctrine, but on the ability to adapt, innovate, and apply unique personal insights to unprecedented challenges.

It also highlights a more uncomfortable truth about American history, that the contributions of black service members have frequently been overlooked or deliberately obscured. Their innovations attributed to the institutional military rather than to the individuals who conceived them. The gradual recognition of Jenkins role in developing elevated sniper tactics represents a small but meaningful correction to this historical pattern. Today, marine snipers training at Quantico still learn to establish firing positions in elevated locations when operating in forested environments. The technical details have evolved with modern equipment and understanding, but the fundamental insight that sometimes you need to meet

the enemy on their own terms then do it better remains unchanged since that humid August day in 1943 when a young sergeant from Mississippi decided to climb a tree. For modern military leaders, Jenkins story offers a valuable lesson about the importance of cultivating and listening to diverse perspectives within the ranks. His unique contribution emerged directly from his premillitary experiences, experiences that differed significantly from those of the officers who had written the tactical doctrines of the time. This suggests that military effectiveness is enhanced not by enforcing uniformity of thought but by creating space for varied backgrounds and approaches to inform collective problem solving.

Dr. Elellanena Westfield in the conclusion to her chapter on Jenkins observed what makes innovation possible in military organizations is not just technical knowledge or tactical doctrine but the lived experiences that service members bring from their civilian lives. Jenkins hunting techniques developed out of necessity in rural Mississippi proved perfectly adapted to the challenges of jungle warfare. This reminds us that diversity of experience is not just a social good but a tactical advantage. In 2017, nearly 74 years after Jenkins actions in New Guinea, the Marine Corps Sniper School officially named its advanced elevated position course the Jenkins Protocol in belated recognition of his contribution.

A small plaque at the training facility bears his photograph and a simple inscription, Sergeant Mitchell P. Jenkins, innovation born of necessity, August 18th, 1943. It’s a modest memorial for an action that saved countless lives and influenced military doctrine for generations. But perhaps it’s fitting for a man who never sought recognition, who simply saw what needed to be done and did it regardless of the rules or potential consequences. The jungles of New Guinea have long since reclaimed the ridges where Jenkins and his fellow Marines fought.

The massive banyan tree that provided his first elevated firing platform has likely fallen and returned to the earth. But the ripple effects of that single decision to climb when others stayed grounded, to adapt when others adhered to doctrine, continue to influence military tactics and training to this day. As we reflect on Jenkins story, we might ask ourselves, would we have had the courage to break the rules when lives depended on it? Would we have recognized the value in an approach that contradicted everything we had been taught?

and would we have had the humility to learn from an enemy’s tactics rather than dismissing them out of hand? These questions remain relevant for military leaders today. As forces around the world continue to adapt to unconventional threats and unprecedented challenges, the capacity to innovate under pressure to see beyond established doctrine when circumstances demand it may be the most valuable legacy of Sergeant Mitchell Page Jenkins and his treetop perch that transform jungle warfare in the Pacific. The story of this one black marine sniper from Mississippi reminds us that sometimes the most effective solution comes not from following the established path, but from having the courage to forge a new one.

In war, as in life, the ability to adapt and innovate often makes the difference between failure and success or between life and death.