Japan Thought Alaska Highway Impossible — Until US Army Built It In 200 Days

October 25, 1942, Beaver Creek, Yukon Territory. Temperatures hovering at 14 degrees below zero. Corporal Refined Sims Jr. of the 97th Engineer Regiment sits a top his Caterpillar D8 Bulldozer, diesel engine rumbling, watching a second bulldozer emerge from the spruce forest ahead. The machine is caked in frozen mud.

Its blade pushes through the last stand of trees, separating two armies of construction. One that has fought north from British Columbia, another that has battled south from Alaska. Private Alfred Galefka climbs down from the approaching D8, part of the 18th Engineers. The two men shake hands. Behind them stretches 1,680 mi of freshly bulldozed Earth, a highway that military planners had declared would take 5 to 10 years to build.

They had done it in 234 days. But this moment, this handshake between a black soldier from Philadelphia and a white soldier from Texas represents far more than an engineering triumph. It represents a declaration. In eight months, through perafrost that swallowed bulldozers whole, through muskegg swamps 25 ft deep, through temperatures that plunged to 70 below zero, American industrial might had conquered terrain that geologists had considered impassible.

The story of how this impossible feat was achieved begins 9 months earlier with a disaster that would reshape the strategic map of North America. December 7th, 1941, Pearl Harbor, territory of Hawaii. At 7:48 in the morning, Japanese aircraft struck the United States Pacific Fleet. In less than 2 hours, 2,43 Americans died.

Eight battleships were damaged or destroyed. The United States was at war. But for military strategists in Washington, the attack revealed something more terrifying than the damage inflicted. a gaping vulnerability in American defenses. Alaska, nearly 600,000 square miles of American territory, sat completely isolated from the continental United States.

No roads connected it to Canada or the lower 48. Every soldier, every bullet, every gallon of fuel had to arrive by ship or aircraft. And with Japanese carriers now prowling the Pacific, those sea lanes were no longer secure. Alaska sat less than 750 mi from the nearest Japanese military base in the Curl Islands, closer to Japan than to Seattle.

If the Japanese seized Alaska, they would control the northern Pacific. They would have bomber bases within striking distance of the American heartland. The unthinkable would become possible. An invasion of the continental United States. In January 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt convened his top military advisers.

The Alaska problem dominated every discussion. The Navy argued that defending Alaska was impossible without reliable sea control. The Army countered that they couldn’t defend sea lanes without forward air bases, and those bases couldn’t be supplied without the answer became obvious. Impossible, but obvious. What happened next defied all odds, a decision that would challenge the very limits of human endurance and engineering.

If you’re invested in this story of how America responded to an existential threat, click the like button to support the channel and subscribe so you don’t miss how this impossible feat was achieved. Here’s what they decided. They needed a road, an overland highway from British Columbia through the Yukon to Alaska, roughly 1,500 miles through some of the most hostile terrain on the planet.

On February 6th, 1942, the United States Army Corps of Engineers officially approved construction of what would become the Alaska Highway. 5 days later, on February 11th, President Roosevelt gave his authorization. Canada agreed to allow construction on three conditions. The United States would pay all costs, the road would be turned over to Canada after the war ended, and construction would begin immediately.

The mission went to the US Army Corps of Engineers. The man chosen to lead the effort was Colonel William M. Hoj, a 48-year-old West Point graduate who had earned his reputation building roads and bridges through the jungles of the Tan in the Philippines. Hoge was blunt, demanding, and pragmatic. When his superiors briefed him on the project in late February, they gave him an impossible timeline, complete a pioneer road, a rough but passable route before winter set in.

That gave him roughly eight months to build 1,500 miles of highway through territory that had never been properly surveyed, through forests so dense that trees grew within feet of each other, through ground that was frozen solid 8 months of the year and turned to soup the other four. Hoge surveyed the project by air in early March.

Flying over the Canadian wilderness, he saw the reality of what Washington was asking. Endless black spruce forests stretching to every horizon, rivers swollen with spring melt, mountain ranges with peaks exceeding 7,000 ft, and beneath it all, perafrost, ground that had been frozen for thousands of years. The army had assigned him four regiments, the 18th, 35th, 340th, and 341st engineerregiments, roughly 4,000 troops.

Hoge is the mathematics. Even working around the clock, four regiments couldn’t clear, grade, and construct 1,500 m of road before October. Not through this terrain. He requested reinforcements. The Army Corps of Engineers had a problem. Most engineer regiments were already deployed to the Pacific or preparing for operations in Europe.

But there were three regiments available. the 93rd, 95th, and 97th Engineer General Service Regiments. All three were segregated African-American units commanded by white officers. In 1942, the US military was strictly segregated. Black soldiers were generally assigned to labor and service roles, not combat positions.

Many Army commanders doubted whether black troops could handle the extreme conditions of subarctic construction. Secretary of War Henry Stimson had previously refused to post black soldiers in far northern regions, believing they couldn’t withstand the cold. But the Alaska Highway project needed manpower. On April 3rd, 1942, the 93rd Engineer Regiment received orders for overseas deployment.

The 95th and 97th soon followed. Approximately 3600 African-American troops, roughly onethird of the total workforce, would help build the Alaska Highway. Colonel Hoge now commanded approximately 11,000 troops, seven regiments, and less than 8 months to complete what many considered the most ambitious construction project since the Panama Canal.

On March 8th, 1942, construction officially began. The strategy was unprecedented. Rather than building from one end toward the other, Hogue deployed his regiments at multiple points along the planned route simultaneously. Crews would work from both north and south, meeting in the middle. This pioneer road approach prioritized speed over perfection.

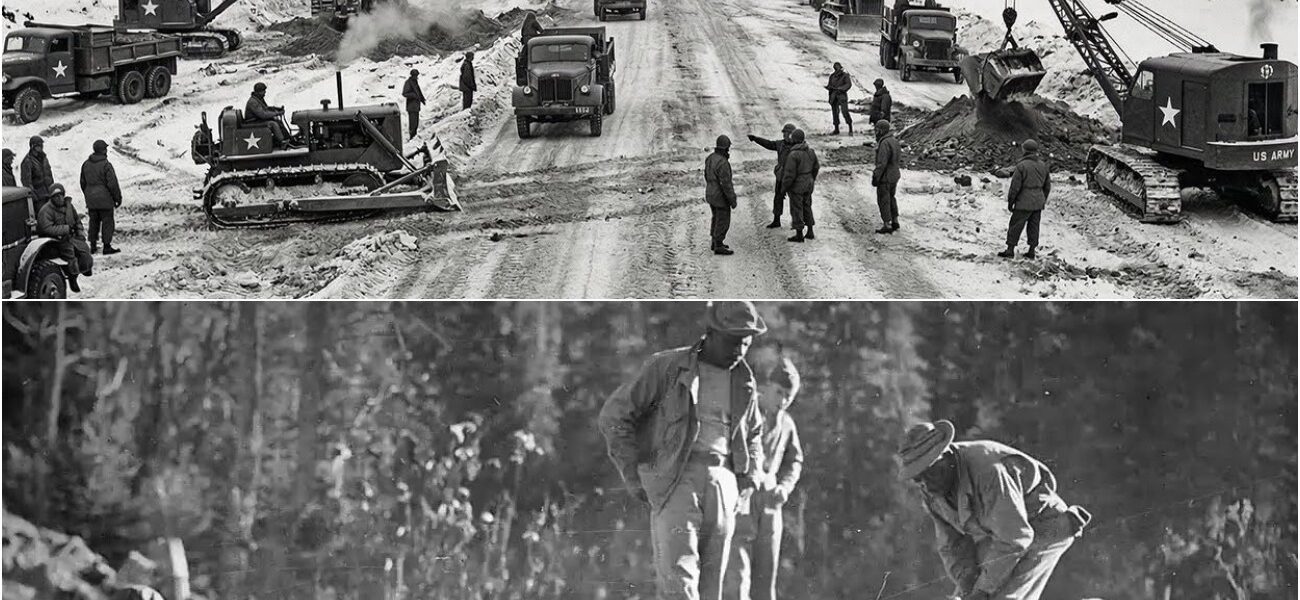

Bulldozers would punch through the forest first, creating a rough path. Follow-up crews would improve the route later. Equipment began arriving by rail at Dawson Creek, British Columbia, mile zero of the highway. The first shipments included 174 steam shovels, 374 blade graders, 94 tractors, and more than 5,000 trucks. Caterpillar D8 bulldozers, 20 ton diesel-powered behemoths became the workh horses of the project.

Some regiments operated with 18 D8s and 20 smaller D4 models. Countless additional bulldozers, cranes, generators, and support vehicles followed. By late April, soldiers and equipment were positioned at staging points across 1,500 miles. at Dawson Creek in British Columbia, at Fort Nelson further north, at White Horse in the Yukon, and at Delta Junction in Alaska.

Seven regiments attacking the wilderness from multiple directions simultaneously. The race against winter had begun. April 1942, Fort St. John, British Columbia. The 341st Engineer Regiment deployed their D8 bulldozers into the spruce forest north of Dawson Creek. The method was brutally simple.

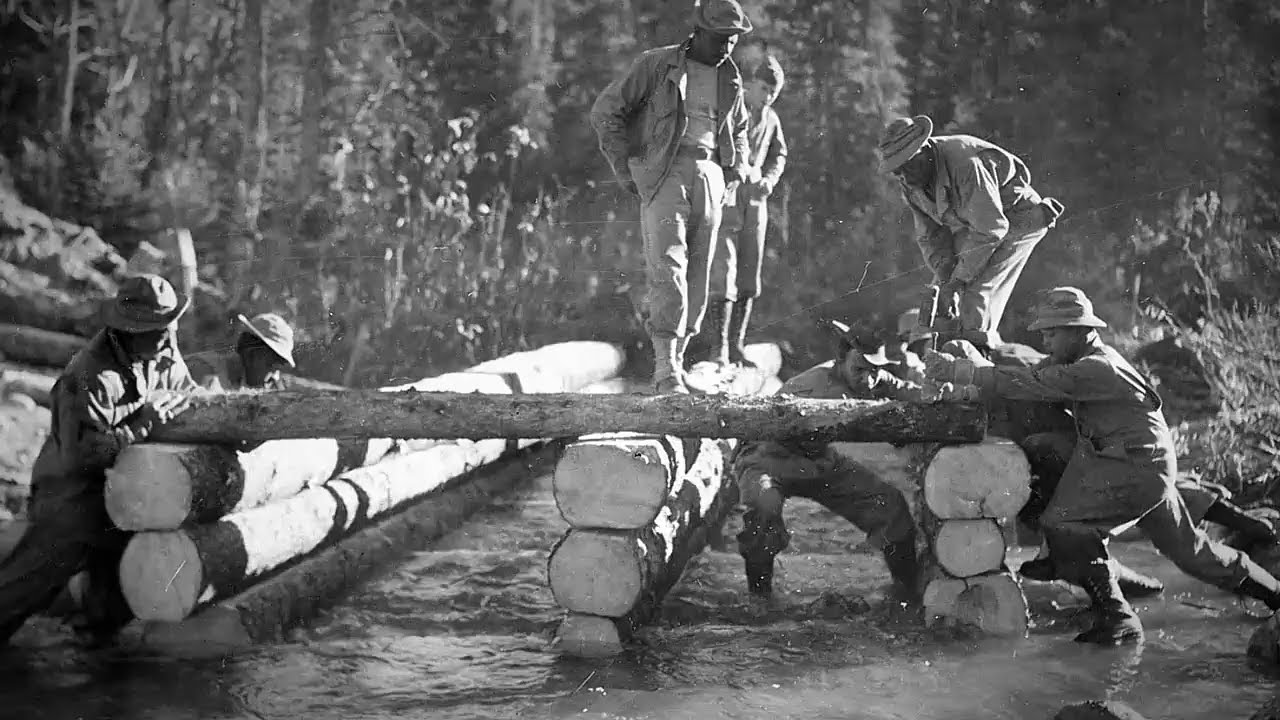

Bulldozers advanced in formation, blades lowered, engines roaring. Trees that had stood for centuries fell in seconds. The dozers pushed through vegetation at a rate of 6 m per day, leaving behind a swath 60 to 90 ft wide. Behind the bulldozers came grading crews, smoothing the torn earth into something resembling a roaded. Behind them came corduroy crews, soldiers felling additional trees and laying them perpendicular across soft ground to create a wooden mat that would support truck traffic.

The work was relentless. 7 days a week, shifts running through the brief arctic night, taking advantage of the midnight sun that gave them nearly 24 hours of daylight. No days off, no breaks. By early May, they had pushed 95 mi north from Dawson Creek. 95 mi in nearly 2 months. At that rate, completing 1,500 m before winter was mathematically impossible. Then they hit the Muskeg.

May 1942, north of Fort St. John. Muske is a wetland formation unique to subarctic regions. A deep accumulation of partially decayed plant matter mixed with water and organic material. In winter, it freezes solid. In summer, it becomes something between a swamp and quicksand. Some Muskeg bogs stretched for miles. Some were 5 feet deep.

Others exceeded 25 feet. When bulldozers first attempted to cross Musk Egg, they simply sank. The vegetation at the surface gave way under the weight and the machines settled into the bog. Engines running, tracks churning, operators helpless as their 20ton tractors slowly disappeared into black organic mud.

One soldier later described it, “If you get a tractor in Muskeg, it just sits there and vibrates. If you leave the engine running, it vibrates until the thing buries itself. The solution was corduroy roads, but on a massive scale. Crews felled trees and laid them across the musk egg. Sometimes building wooden mats 15 ft deep before the road surface could be placed on top.

It was labor inensive, timeconuming, and exhausting. One corduroy section could consume an entire day’s progress. By the end of May, total progress across all seven regiments stood at less than 200 miles. Springthaw had turned much of the route into mud. Equipment broke down constantly in the wet conditions. Morale began to falter.

Then on June 3rd, 1942, everything changed. June 3, 1942, Dutch Harbor, Illutian Islands, Alaska. At 5:45 in the morning, Japanese aircraft from carriers Ryujo and Juno attacked the American military base at Dutch Harbor. Wave after wave of bombers struck the naval station. When the attack ended, 43 Americans were dead. Over 100 were wounded.

Fuel storage tanks burned. The following day, June 4, Japanese forces returned and bombed Dutch Harbor again. Then on June 7th, Japanese troops landed on Kiska Island in the illusions. On June 11th, they occupied Au Island. For the first time since the War of 1812, foreign forces occupied American territory. The psychological impact was immediate.

What had been theoretical, the threat of Japanese invasion became real. If Japan could seize the illusions, Alaska itself was vulnerable. And if Alaska fell, the entire West Coast faced threat. News of the attacks reached construction crews along the Alaska Highway within days. For soldiers working in the Canadian wilderness, the war suddenly felt very close.

These weren’t just roads they were building. They were lifelines, defense infrastructure, the only overland route to supply American forces in Alaska. Work intensity increased dramatically. In July 1942, construction crews laid down 400 m of road. 400 m in a single month. The pace was ferocious. Bulldozers ran continuously, cooling their engines only for repairs.

Operators worked shifts until exhaustion forced them to stop. The Japanese presence in the illusions just hundreds of miles from the northern terminus of the highway drove every decision. But the pace came at a cost. The challenges weren’t just muskag anymore. July 1942, Yukon territory.

When bulldozers cleared vegetation to create the roaded, they exposed the ground beneath. And in much of the Yukon and northern British Columbia, that ground was perafrost, earth that had been frozen continuously for years, sometimes centuries. The problem emerged within hours of clearing. As sunlight hit the newly exposed perafrost, it began to thaw.

But perafrost doesn’t thaw evenly. Ice crystals within the soil melt, creating voids. The ground becomes unstable. What was solid earth in the morning became black mud by afternoon. A thick, viscous sludge that could swallow bulldozers, trucks, and anything else that ventured onto it. One engineering officer described the situation.

We’d clear a section in the morning. By late afternoon, the same section would be impassible. Even the bulldozers that created the road couldn’t cross it anymore. The solution required changing their entire construction methodology. Instead of removing vegetation and letting the perafrost thaw naturally, crews learned to cover the exposed roaded immediately with fill material, gravel, rocks, timber, anything that would insulate the perafrost and prevent thawing.

The road had to be built on top of the frozen ground, not through it. It added time. It added labor. But it was the only way to create a road that would remain passable. By late July, total progress exceeded 800 m, halfway to completion. The mathematics now suggested success was possible if they could maintain the pace, if equipment held out, if weather cooperated, if the perafrost solutions worked.

But August brought its own challenges. August 1942, northern British Columbia. Summer heat arrived. Temperatures climbed into the 80s and 90s, tropical by subarctic standards. With heat came mosquitoes, clouds of them. Swarms so thick that soldiers wrapped cloth around their faces to avoid breathing them in. Work slowed as men fought both the terrain and the insects. Dust became a hazard.

The newly bulldozed roads, baked by sun, turned to powder. Vehicles traveling the completed sections kicked up dust clouds so thick that drivers couldn’t see 10 ft ahead. Convoys separated, losing contact with each other in brownout conditions. But the work continued. By the end of August, construction crews had completed over,00 miles of Pioneer Road.

400 m remained 2 months until the target deadline. Then in early September, they hit the final barrier, September 1942, west of Kuwan Lake, Yukon Territory. The section west of Kuwan Lake represented some of the most difficult terrain on the entire route. mountain passes exceeding 4,000 ft, steep grades, and beneath it all, extensive perafrost that had to be carefully managed.

Progress slowed to a crawl, 3 m per day, sometimes less. The cold was returning. Daytime temperatures dropped toward freezing. Soldiers knew that once serious winter arrived, typically by late October, construction would become nearly impossible. On September 24th, 1942, crews from the 340th Engineer Regiment working north met crews from the 35th Engineer Regiment working south at Contact Creek near the British Columbia Yukon border.

The southernsector was complete, but the northern section, the most difficult terrain between White Horse and Delta Junction remained unfinished. Approximately 200 m of road across some of the harshest landscape in North America. 4 weeks until winter, the race entered its final phase. To understand how the Alaska Highway was built in 8 months when conventional engineering suggested it would take 5 to 10 years, one must understand the philosophy behind the pioneer road concept.

Traditional highway construction followed established patterns. Survey teams would spend months, sometimes years, identifying optimal routes. They would calculate grades, assess drainage, evaluate soil conditions, plan bridge locations, and design a road built to last. Construction would proceed methodically, section by section, ensuring each segment met engineering standards before moving forward.

The Alaska Highway rejected every one of these principles. The requirement issued to Colonel Hage was stark. create a passable route for military trucks by October 1942. Not a highway, not a permanent road, a route. Something that could move troops and supplies before winter made construction impossible.

The mathematics were brutally simple. To build 1,500 miles in 8 months meant completing approximately 6.25 m per day averaged across the entire project. But surveying alone, done properly, would consume months. Conventional bridge construction would add months more. If they followed standard engineering practices, winter would arrive before they completed 500 miles.

So, they abandoned standard engineering practices entirely. The pioneer road method prioritized one thing above all else, forward progress. Bulldozers didn’t wait for survey crews to identify optimal routes. They punched directly through the forest wherever the terrain allowed. If a mountain stood in the way, they went around it, even if that meant steep grades and hairpin turns.

If a river blocked progress, they built temporary timber bridges, knowing they’d be replaced later. Specifications that would define the final highway simply didn’t apply to the pioneer road. Width: 12 to 18 ft instead of the planned 36 ft. Surface raw earth instead of gravel. grades, whatever the bulldozers could climb instead of the maximum 8% specified for permanent roads.

The decision to use this approach was both pragmatic and revolutionary. It meant accepting that the road built in 1942 would be rough, dangerous, and barely adequate. But it would exist, and existence was the only requirement that mattered. Colonel Hage described the philosophy in reports. We built where the bulldozer would go.

If we couldn’t go through an obstacle, we went over it. The road wasn’t built for passenger cars. It was built for bulldozers and military trucks. This approach also determined equipment selection. The Caterpillar D8 bulldozer became the defining machine of the project because it offered the optimal balance of power and mobility.

At 20 tons, with a diesel engine producing approximately 80 horsepower, the D8 could knock down trees three feet in diameter and push through obstacles that would stop lighter machines, but it was still maneuverable enough to navigate difficult terrain. Some regiments operated with 18 D8s and 20 smaller D4 models.

The D8s led, clearing the widest path possible. The D4s followed, grading and smoothing. Behind them came support equipment, trucks, grers, and in critical sections, cranes for bridge work. The decision to deploy seven regiments simultaneously across the route instead of building consecutively from one end multiplied both progress and risk.

It meant coordination became extremely difficult. Regiments were separated by hundreds of miles with minimal communication. It meant supply lines stretched dangerously thin with equipment and materials arriving weeks late or not at all. It meant redundant efforts as crews sometimes had to redo work that didn’t align with adjacent sections.

But it also meant that when progress bogged down in one area due to muske or perafrost, other sections continued advancing. The overall project kept moving forward even when individual segments stalled. Perhaps the most consequential decision was accepting racial integration of the workforce, not because of progressive values, but because of practical necessity.

The three segregated African-Amean regiments represented onethird of total manpower. Without them, the timeline was impossible. With them, the project had enough troops to sustain the multiffront construction approach. The 93rd Engineer Regiment worked primarily in the Yukon Territory, building critical sections from Carross to the Teslan River.

The 95th Engineer Regiment, despite being the most experienced with heavy equipment, was initially given hand tools, while less experienced white units received bulldozers, a decision based on racism rather than competence. Only after protests did they receive proper equipment.

The 97th EngineerRegiment built the northernmost sections in Alaska, working in some of the coldest and most isolated conditions on the entire route. All three black regiments lived in tents through the subarctic winter of 1942-43 while some white units had heated barracks. All three faced discrimination, segregation, and unequal treatment.

Yet all three completed their assigned sections on schedule or ahead of schedule. The philosophy behind the Alaska Highway was this. Accept temporary solutions. Prioritize speed over perfection. Deploy overwhelming force and push forward regardless of obstacles. It was engineering as warfare. Not against a human enemy, but against geography, time, and physics.

And against every reasonable expectation, it worked. September 24th, 1942. Contact Creek, British Columbia, Yukon border. With the southern sector complete, all remaining resources concentrated on the final 200-mile gap between White Horse and Delta Junction. This section presented every challenge the project had encountered.

Mountains, perafrost, Muske, and now the arrival of autumn cold. Temperatures began dropping below freezing at night. Diesel fuel thickened in the cold, making engines harder to start. Hydraulic systems on bulldozers moved sluggishly until warming up. Men worked in layers of clothing, though few had been issued proper Arctic gear.

The 97th Engineer Regiment, working the northernmost sections in Alaska Territory, faced conditions their mostly southern troops had never experienced. Many soldiers in the 97th came from Georgia, Florida, and the Carolas, regions where temperatures rarely dropped below freezing. Now they worked in conditions approaching 0° building road through wilderness more remote than anything in the continental United States.

Despite the challenges, progress continued. The mathematics had become clear. If they maintained even minimal forward progress, 3 to four miles per day, they would complete the route before serious winter arrived. On October 20th, 1942, crews from the 18th Engineer Regiment working south and crews from the 97th Engineer Regiment working north were less than 10 mi apart. Final completion was days away.

October 25th, 1942, Beaver Creek, Yukon Territory, 14° below zero. At approximately 2 in the afternoon, Corporal Refines Sims Jr. of the 97th Engineer Regiment. An African-American soldier from Philadelphia drove his Caterpillar D8 Bulldozer through the final stand of spruce trees separating north from south.

Emerging from the opposite direction came Private Alfred Jalufka of the 18th Engineer Regiment, a white soldier from Texas. The two men climbed down from their bulldozers. They shook hands. Behind Sims stretched the northern sections built primarily by the 97th and 18th Engineer regiments through some of the most difficult terrain on the route.

Behind Jalufka stretched the southern and central sections built by five regiments working through their own challenges across 1,400 m. The Alaska Highway was complete. Or more accurately, a rough pioneer road now connected Dawson Creek, British Columbia to Delta Junction, Alaska. Approximately 1680 miles built in 234 days, eight months from start to finish.

Photographs captured the handshake between Sims and Galofa. In the context of 1942 America, a nation where racial segregation was legally enforced, where black soldiers faced discrimination even while serving their country. The image was remarkable. Two soldiers, one black and one white, meeting as equals at the completion of an impossible task.

But the highway wasn’t truly finished. Not yet. November 1942. Various locations along the Alaska Highway. The Pioneer Road existed, but it was barely passable. Grades in some sections exceeded 25%. Turns were so sharp that trucks had to back up and make multiple attempts to navigate them. Bridges were temporary timber structures that groaned under the weight of heavy vehicles.

The road surface was raw earth, mud when it rained, dust when it dried, ice when temperatures dropped. Public works administration P contractors now moved in behind the military crews, beginning the monthslong process of upgrading the pioneer road to actual highway standards. They would straighten curves, reduce grades, build permanent bridges, add gravel surfacing, and address drainage issues.

But for military purposes, the pioneer road was sufficient. Truck convoys could now travel overland from the continental United States to Alaska. The isolation that had made Alaska vulnerable was broken. On November 20th, 1942, a formal dedication ceremony took place at Soldier Summit, mile 1,61 of the highway near Kuwan Lake in the Yukon.

Despite temperatures well below zero, approximately 250 American and Canadian officials gathered for the ribbon cutting. Radio broadcasts carried the ceremony across North America. Brigadier General James O’ Conor, who had replaced Colonel Hoge as project commander in August, presided over the ceremony.

Canadian and American flags flew side by side. Military bands played despite frozen instruments. Speeches praised the achievement and the soldiers who made it possible. Notably absent from most official accounts of the ceremony, detailed recognition of the African-American regiments who had built one-third of the highway. The 93rd, 95th, and 97th Engineer Regiments received minimal mention in contemporary press coverage.

The iconic photograph of Corporal Sims and Private Galofa shaking hands was widely published, but often without identifying Sims by name or noting that he was an African-Amean soldier. The human cost of construction was significant. Approximately 30 soldiers died during the project from vehicle accidents, equipment failures, exposure, and illness.

Disease spread through construction camps, affecting both soldiers and indigenous populations. Along the route, several indigenous communities experienced devastating outbreaks of influenza and other illnesses brought by the sudden influx of thousands of outsiders. Environmental impact was enormous. Millions of trees were felled.

Rivers were bridged or diverted. Wildlife habitat was disrupted across 1680 mi of wilderness. The highway created a permanent corridor through territory that had been largely untouched by industrial development. The financial cost was staggering. Final figures placed direct construction costs at approximately 138 million, roughly $2.

5 billion in 2024. This made the Alaska Highway the most expensive World War II construction project undertaken by the United States. And that figure didn’t include the cost of maintaining the 11,000 troops during construction, nor the subsequent upgrade work by P contractors that would continue into 1943. But the strategic cost of not building it would have been incalculable.

The Alaska Highway completed in October 1942 consisted of length and route total distance approximately 1,680 m 2700 km from Dawson Creek, British Columbia to Delta Junction, Alaska, later optimized to 1,422 mi by 1946 after straightening curves and improving grades. Modern highway as of 2012, 1,387 miles after decades of continued realignment.

Physical infrastructure over 133 bridges ranging from simple timber spans to major river crossings. More than 8,000 culverts for drainage, 200 plus miles of corduroy roads, logs laid across Muskag. surface, raw earth, and limited gravel in 1942. Upgraded to gravel by 1943, fully paved by the 1960s. Personnel total military workforce approximately 11,000 US Army troops from seven engineer regiments.

White regiments 18th, 35th, 340th, 341st engineer regiments, approximately 7,000 troops. Black regiments, 93rd, 95th, and 97th Engineer General Service Regiments, approximately 3,600 troops. Civilian Contractors, approximately 16,000 Canadian and American civilians worked on upgrade phases.

Command Colonel, later Brigadier General William M. Hyogue, marched to August 1942. Brigadier General James Okconor August 1942. Completion equipment. First shipments included 174 steam shovels, 374 blade graders, 94 tractors, 5,000 plus trucks. Primary bulldozers, Caterpillar D8, a 20ton diesel, and D4 lighter models.

Support equipment, cranes, generators, maintenance vehicles, fuel trucks. Total equipment value approximately $1 million 1942 roughly $17 million in 2024. Construction timeline authorization February 11th, 1942. President Roosevelt groundbreaking March 8th to 9th, 1942. Sources vary slightly. First linkup September 24th, 1942.

Contact Creek, Southern Sector. Final linkup October 25th, 1942. Beaver Creek, Northern Sector. Official opening, November 20th, 1942. Soldiers Summit dedication. Total construction time 234 days, approximately 8 months. Open to the public, 1948 after military restrictions lifted. Casualties and impact. Military deaths during construction, approximately 30 from accidents, exposure, illness.

Indigenous communities impacted. Multiple communities experienced disease outbreaks from contact with construction crews. One notable incident, 12 soldiers drowned at Charlie Lake when pontoon boat sank. Postwar fate. Canadian sections turned over to Canadian government as agreed. 1946. Continuous upgrading and realignment.

1943 to present. Strategic importance declined after Illutian Island secured in 1943 became vital civilian transportation corridor by the 1950s. Today major tourist attraction and commercial route fully paved maintained year round. The comparative analysis the Alaska Highway achievement becomes clear when compared to similar projects.

Panama Canal, 1904 to 1914, 10 years to build, approximately 51 mi long. Cost $375 million, $1 1914. Workers approximately 40,000 at peak. Casualties over 5600 deaths. Hoover Dam 1931 to 1936, 5 years to build. Cost $49 million, $1 1936. workers approximately 21,000 at peak. Casualties 96 deaths.

Alaska Highway 1942 8 months to build 1680 mi long. Cost 138 million $1 1942. Workers 11,000 military plus 16,000civilian contractors. Casualties 30 military deaths during initial construction. The Alaska Highway represented a different philosophy of construction. The Panama Canal and Hoover Dam were built to last centuries with every decision optimized for permanence.

The Alaska Highway was built to exist before winter, built for immediate military necessity rather than long-term permanence. That philosophical difference defined everything. the pioneer road approach, the multifront construction strategy, the acceptance of temporary solutions, and the willingness to rebuild and improve the route in subsequent years.

Recognition and legacy. For decades after the war, the contributions of the African-American regiments received minimal recognition. The 93rd, 95th, and 97th Engineer Regiments were often omitted from official histories or mentioned only in passing. Not until the 1990s did substantial efforts begin to document and honor their role.

In 1993, the Black Veterans Memorial Bridge was dedicated along the Alaska Highway, one of the few physical monuments specifically recognizing the African-American soldiers who built onethird of the route. In 2017, historian Christine and Dennis Mccclure published We Fought the Road, documenting the experience of the 93rd Engineer Regiment and the racism that contaminated the project.

The Alaska Highway was designated an international historical engineering landmark in 1996, recognizing its significance as one of the great engineering achievements of the 20th century. October 25th, 1942, Beaver Creek, Yukon Territory. When Corporal Refines Sims Jr. and Private Alfred Jalofka shook hands in the frozen wilderness of the Yukon, they concluded a project that changed the strategic map of North America.

But the handshake itself, captured in a photograph that would be published in newspapers across the United States, represented something that transcended engineering. In 1942, America was a segregated nation. Black soldiers trained in separate camps, ate in separate mesh halls, and fought in separate units.

The army maintained these divisions rigidly, believing that integration would undermine military effectiveness. Many military leaders doubted whether black soldiers could perform complex technical work or handle extreme environmental conditions. The Alaska Highway proved them wrong. The 93rd Engineer Regiment completed their sections on schedule.

The 95th Engineer Regiment, despite initially being denied bulldozers and forced to work with hand tools, performed when finally given proper equipment. The 97th Engineer Regiment built through the harshest conditions on the entire route, working in temperatures that soldiers from the American South had never imagined, building roads that are still in use today.

The photograph of Corporal Sims and Private Galofa standing together as equals, representing the completion of an impossible task, challenged the assumptions underlying segregation. Here were black and white soldiers who had accomplished together what experts declared could not be done. The image suggested a different future. But that future would be slow in coming.

After completing the Alaska Highway, the three black engineer regiments were transferred to other theaters. The 93rd went to the Illusions, the 95th and 97th to Europe. They continued to face discrimination and segregation throughout the war. Not until 1948 did President Truman order the integration of the US military.

The Alaska Highway underwent continuous transformation. By 1946, when the Canadian sections were transferred to Canadian control, the route had been shortened to 1422 mi through improved alignments. By the 1960s, it was fully paved. By 2012, modern routing had reduced the length to 1387 mi. Today, the highway is a major tourist attraction.

Hundreds of thousands of travelers drive the Alaska Highway each year, experiencing wilderness that the 1942 soldiers saw for the first time. The road that took 8 months of desperate construction to create now takes about 3 days of casual driving to traverse. But the original Pioneer Road, that raw path bulldozed through the forest in 1942, remains visible in places.

Old alignments abandoned during later improvements can still be seen alongside the modern highway. Wooden corduroy roads preserved by cold and dryness occasionally surface when modern road crews excavate. Historical markers document the original route. The Japanese threat that drove the highways construction proved less severe than feared.

After the Illutian Islands were retaken in 1943, the strategic urgency faded. The vast majority of supplies to Alaska during World War II continued to travel by sea. The highway carried only a small fraction of total tonnage. But strategic value cannot be measured solely in tons delivered. The Alaska Highway accomplished something more profound than logistics.

It declared that American territory would not remain isolated. It demonstrated thatindustrial might, properly focused, could overcome any geographic obstacle. It proved that seemingly impossible timelines could be met through determination and sacrifice. The lesson of the Alaska Highway extends beyond military engineering.

It demonstrated what becomes possible when conventional wisdom is set aside, when traditional methods are abandoned in favor of pragmatic solutions, when the only requirement is forward progress regardless of perfection. The Alaska Highway was not the best engineered road of 1942. It was rough, dangerous, and barely adequate, but it existed, and existence was what mattered.

The highway built in 234 days through subarctic wilderness still connects Alaska to the continental United States. It still serves as a lifeline for remote communities. It still carries commercial traffic, tourists, and military vehicles. The temporary solution built for wartime necessity became the permanent corridor that defined northern transportation for the rest of the century.

When engineers examine the Alaska Highway today, they see a different lesson than the 1942 planners envisioned. They see not just the road that was built, but the philosophy that built it. That perfection can be the enemy of completion. That temporary solutions can become permanent successes, and that what experts declare impossible may simply require a different approach.

Corporal Rafine Sims Jr. returned to Philadelphia after the war. Private Alfred Julka returned to Texas. Their handshake in the Yukon wilderness lasted only seconds, captured in a single photograph, but it marked the conclusion of one of the great engineering achievements of World War II. A highway that military planners said would take a decade built in less than 8 months through terrain that geologists said was impassible.

the impossible highway, the road that shouldn’t exist. The 1,680mi declaration that American will and industrial might could overcome any obstacle, conquer any wilderness, and achieve any objective if the only alternative was defeat. In that single fact lies the entire story of how the Alaska Highway was built and why it mattered.