What MacArthur Said When Patton Died

December 21st, 1945. Tokyo, Japan. General Douglas MacArthur sits in his office in the Daichi Assurance Building, the headquarters from which he rules occupied Japan. An aid brings him an urgent telegram from Europe. MacArthur reads it quickly. His expression, normally inscrable, shows a flash of something. Surprise, perhaps sadness. He sets the telegram down on his desk. General George S. Patton Jr. is dead. He died that morning in a military hospital in H Highleberg, Germany, 12 days after a car accident that broke his neck and left him paralyzed.

Patton was 60 years old. He’d survived two world wars, multiple combat commands, and countless battles. He’d led armies across North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany. He was one of the most famous generals in American history. And now he was gone, not killed in combat, but dead from injuries sustained in a minor car accident on a country road in Germany. MacArthur, according to accounts from staff officers present, sits quietly for several moments after reading the news. Then he begins drafting a statement.

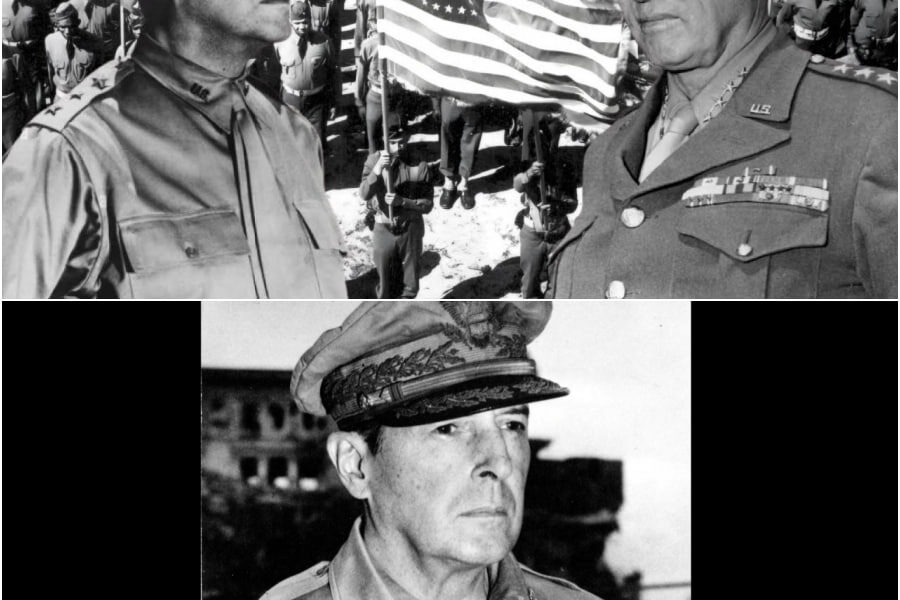

This is the story of what MacArthur said when Patton died, how MacArthur memorialized his fellow general, and what MacArthur’s words revealed about his view of Patton and of military greatness. Let’s go back to understand the relationship between MacArthur and Patton and why Patton’s death mattered to MacArthur. Douglas MacArthur and George Patton were not close friends. They served in different theaters during World War II. MacArthur in the Pacific, Patton in Europe. They rarely met and corresponded infrequently. Their careers followed parallel but separate paths, but they knew each other.

They had served together briefly decades earlier and they shared certain characteristics that made each recognize something in the other. MacArthur was born in 1880. Patton was born in 1885. Both came from military families. MacArthur’s father, Arthur MacArthur Jr., was a Civil War hero and a general. Patton’s grandfather had been a Confederate colonel and his family revered military tradition. Both men attended West Point, though at different times. MacArthur graduated in 1903, first in his class. Patton graduated in 1909 after an extra year due to academic struggles.

Their first documented interaction came during World War I. Both served in France in 1918. MacArthur commanded the 42nd Rainbow Division. Patton commanded tank units. According to military records, they met at least once during the war, though accounts of this meeting are sparse. After World War I, their paths crossed again in the United States. In the 1920s and 1930s, both were rising officers in the peacetime army. According to various accounts, they encountered each other at military functions and in Washington.

The most significant interaction between MacArthur and Patton came in 1932 during the Bonus Army incident. According to official records, MacArthur, then Army Chief of Staff, commanded the operation to clear World War I veterans from their encampment in Washington, DC. Patton, then a major, commanded cavalry and tank units that participated in the operation. This was a controversial episode. Veterans who had served in World War I were camping in Washington, demanding early payment of bonuses promised to them. President Herbert Hoover ordered the army to clear them out.

MacArthur commanded the operation. Patton was one of the officers executing MacArthur’s orders. According to contemporary accounts, Patton followed MacArthur’s orders without question. Years later, both men would have different recollections of the event, but in 1932, Patton served under MacArthur in a difficult and unpopular operation. After 1932, their paths diverged. MacArthur went to the Philippines to organize the Philippine Army. Patton remained in the United States, continuing his career in the cavalry and later in armored forces. During World War II, they served in completely different theaters and had minimal direct contact.

According to available records, they exchanged few if any letters during the war. They were aware of each other’s achievements through news reports and military communications, but they weren’t collaborating or even communicating regularly. However, both men followed similar approaches to warfare. Both believed in aggressive offense. Both valued mobility and boldness. Both cultivated distinctive public images. MacArthur with his corn cob pipe and sunglasses. Patton with his ivory-handled pistols and profane speeches. Both were also controversial. MacArthur feuded with civilian leadership and was famously difficult to manage.

Patton slapped soldiers, made politically damaging statements, and constantly created problems for Eisenhower. By December 1945, the war was over. MacArthur was supreme commander for the Allied powers in Japan, essentially ruling the country during occupation. Patton had been commanding the 15th Army in Germany, a largely administrative posting documenting the war’s history. But Patton’s position in Germany had become problematic. According to documented accounts, Patton had made controversial statements about Nazis, comparing Nazi party membership to Democratic or Republican party membership in America.

These comments created outrage. Eisenhower relieved Patton of his command of the Third Army in October 1945 and gave him the less important 15th Army posting. Patton was unhappy with this demotion. According to his diary entries from October and November 1945, he felt unappreciated and bitter about his treatment. He was planning to return to the United States and retire from active service. Then on December 9th, 1945, Patton was riding in a car near Mannheim, Germany. According to the official accident report, his car collided with a US Army truck at low speed.

Patton was thrown forward and struck his head on a metal partition in the car. The impact broke his neck and severed his spinal cord, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. For 12 days, Patton lay in a hospital in H Highleberg. According to medical records and accounts from those present, he was conscious and aware, but unable to move. He knew he was dying. On December 21st, 1945, at 5:50 p.m., Patton died from a pulmonary embolism and congestive heart failure.

News of Patton’s death spread quickly through military channels. According to various accounts, the news reached MacArthur in Tokyo on December 21st, December 22nd, Tokyo time due to the time difference. MacArthur’s immediate reaction is documented in accounts from staff officers present. According to these sources, MacArthur received the telegram informing him of Patton’s death and read it without comment. He then asked to be left alone for a few minutes. After this brief period, according to these accounts, MacArthur called in his staff and began dictating a statement about Patton’s death.

The statement MacArthur issued is preserved in military archives and was published in newspapers. According to the official text, MacArthur’s statement read, “The death of General Patton is a great loss to the army and to the nation. He was one of the most brilliant soldiers America has produced. His daring and resourcefulness were matched by his tactical skill and strategic vision. He was a great captain who will take his place in history with the finest field commanders of all time.

This statement was formal and measured, typical of official military tributes. But according to accounts from those present when MacArthur dictated it, MacArthur spoke more extensively about Patton before settling on this concise statement. According to his aid, Colonel Sydney Huff’s later account, MacArthur said something to the effect that Patton was a warrior in the truest sense and that men like Patton are born for war and die when war is over. Huff’s account suggests MacArthur saw Patton as a man whose natural element was combat and who struggled in peace time.

This wasn’t necessarily a criticism. MacArthur himself was a warrior who thrived in war and found peace time frustrating. MacArthur’s official statement was cabled to Washington and released to the press. According to newspaper accounts from December 22nd, 1945, MacArthur’s tribute appeared alongside statements from other military leaders. General Eisenhower, who had commanded Patton in Europe, issued a statement saying, “General Patton was one of the most brilliant soldiers of his time. His boldness, energy, and tactical genius were vital to Allied victory in Europe.” General George Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, said, “General Patton’s death is a great loss to the Army and to the nation.

He was a combat leader without peer.” President Harry Truman issued a statement, “The nation has lost one of its greatest soldiers. General Patton’s service in two world wars demonstrated the highest traditions of American military leadership.” But according to various accounts, MacArthur’s private comments about Patton went beyond his official statement. According to his biographer, William Manchester, who interviewed people who worked with MacArthur, MacArthur privately expressed admiration for Patton’s aggressive leadership and combat success. According to these accounts, MacArthur saw Patton as a kindred spirit, another general who understood that war required bold action, aggressive leadership, and willingness to take risks.

MacArthur himself embodied these qualities, and he recognized them in Patton. However, according to these same sources, MacArthur also recognized that both he and Patton were controversial figures who created problems for civilian leadership. Both had been criticized for insubordination. Both had feuded with superiors. Both had said things that created political problems. MacArthur’s statement about Patton being one of the most brilliant soldiers America has produced was significant. According to those who knew MacArthur, he rarely gave such unqualified praise to other generals.

MacArthur was confident in his own abilities and sometimes dismissive of others. His praise of Patton suggested genuine respect. In the days following Patton’s death, MacArthur received more information about the circumstances. According to various accounts, MacArthur was troubled by the fact that Patton had died in a car accident rather than in combat. According to aid, Colonel Sydney Huff’s account, MacArthur said something about it being tragic that a warrior like Patton didn’t die in battle. This reflected a romantic view of military service that both MacArthur and Patton shared.

The idea that great generals should fall in combat, not in peaceime accidents. MacArthur did not attend Patton’s funeral. According to official records, Patton was buried on December 24th, 1945 in the American military cemetery in Luxembourg among the soldiers of his Third Army. MacArthur remained in Tokyo, occupied with the duties of ruling Japan. According to available records, MacArthur did not send a personal representative to Patton’s funeral. He did not send a reef or any personal tribute beyond his official statement.

The distance between Tokyo and Luxembourg and MacArthur’s responsibilities in Japan made attendance impractical. In the years after Patton’s death, MacArthur occasionally spoke about Patton in speeches and interviews. According to various accounts, MacArthur always spoke respectfully of Patton as a great combat leader. In his 1964 memoir, Reiniscances, MacArthur devoted a brief passage to Patton. According to the text, MacArthur wrote, “George Patton was one of the great captains of war. His tactical brilliance and aggressive leadership contributed immeasurably to Allied victory in Europe.

This was consistent with MacArthur’s public statement from 1945. Respectful, admiring, but not deeply personal. The historical record suggests that MacArthur and Patton respected each other but were not close friends. They recognized similar qualities in each other. boldness, aggression, showning shship, and a romantic view of warfare. But they served in different spheres and had limited personal interaction. What MacArthur said when Patton died was formal and respectful. The death of General Patton is a great loss to the army and to the nation.

He was one of the most brilliant soldiers America has produced. These words preserved in official records and contemporary newspaper accounts show MacArthur paying tribute to a fellow general in conventional military language. But according to accounts from those close to MacArthur, his private comments suggested deeper feelings. MacArthur saw Patton as a warrior who belonged on the battlefield, not behind a desk. He saw Patton’s death as the end of an era. the passing of a type of general who thrived in combat but struggled in peace.

MacArthur himself would face similar challenges. Like Patton, MacArthur was a combat leader who clashed with civilian authority. Like Patton, MacArthur would eventually be removed from command, fired by President Truman in 1951 for insubordination during the Korean War. Perhaps MacArthur recognized in Patton’s fate a preview of his own. Both were warriors who couldn’t quite fit into peacetime military service. Both created controversy. Both were brilliant in battle, but difficult to manage. What MacArthur said when Patton died was measured and appropriate.

But what MacArthur might have thought that he and Patton were similar souls, warriors born for combat who struggled when the fighting stopped may have gone unspoken. The historical record gives us MacArthur’s official statement and a few reported private comments. It shows respect and recognition of Patton’s military achievements, but the full extent of MacArthur’s reaction to Patton’s death, his private thoughts and feelings remain largely undocumented. What we know is this. When George Patton died, MacArthur called him one of the most brilliant soldiers America has produced and a great captain who will take his place in history with the finest field commanders of all time.

Coming from MacArthur, a general not known for praising others generously, these words represented significant recognition. They placed Patton in the highest ranks of American military leadership, not just in MacArthur’s personal estimation, but in the judgment of history. And perhaps that’s what mattered most to both men. Not their relationship with each other, but their place in history as warriors and commanders. MacArthur’s tribute to Patton acknowledged that Patton had earned that place, that his name would endure alongside the great military leaders of the past.

For two generals who cared deeply about legacy and historical reputation, this recognition from one to the other carried weight. MacArthur was saying that Patton had achieved what both men sought, greatness in the profession of arms, a place in the pantheon of military history. That was what MacArthur said when Patton died. Words that granted Patton the immortality that both generals craved.