What Bradley Told Eisenhower After Patton Did The Unthinkable at Bastogne

December 26th, 1944. If General George Smith Patton hadn’t smashed through to Baston that day, 10,000 United States soldiers would have been wiped out. Not captured, not forced to surrender. Wipe out. Surrounded by eight German divisions, cut off from supplies, freezing in the worst blizzard Europe had seen in decades.

The 101st Airborne was dying slowly, painfully. Every military expert said relief was impossible. The weather made it impossible. The distance made it impossible. The Germans made it impossible. But they didn’t count on one man. The man they called old blood and guts. General George Smith Patton had just promised Supreme Commander Eisenhower he’d do the impossible in 72 hours.

When he made that promise, the room fell silent. Grown men hardened generals who’d seen years of combat thought George Smith Patton had lost his mind. They called him old blood and guts because he’d earned that name charging into battle while other generals commanded from behind the lines because his men said he had guts and their blood.

Now he was about to attempt the most audacious military maneuver of World War II. What happened next would shock the German high command, amaze the Allied forces, and force General Omar Bradley to tell Eisenhower something he never thought he’d say about George Smith Patton. This is what happened next. The 16th of December 1944, Adolf Hitler launched his final desperate gamble in the West.

Operation Watch on the Rine, what history would remember as the Battle of the Bulge. Three German armies, 30 divisions, over 400,000 men smashed into the weakest point of the Allied line in the Arden’s forest of Belgium. The attack was devastating. Within 48 hours, German Panzer divisions had torn a bulge 50 mi deep into United States lines.

Entire regiments were surrounded. Communications collapsed. In the chaos and confusion, one critical crossroads town became the key to everything. Baston. Baston wasn’t just another Belgian town. Seven major roads converged there. Whoever controlled Baston controlled the entire region. If the Germans captured it, they could race west to the Muse River, split the Allied armies, and potentially reach the coast.

The invasion of Europe would unravel. The United States Army rushed the 101st Airborne Division to Baston. These paratroopers weren’t supposed to fight tank battles. They were lightly armed infantry dropped behind enemy lines. Now they face German armor. By December 21st, 1944, the noose closed completely. Eight German divisions surrounded Baston. The 101st was cut off.

Inside the perimeter, acting commander Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe commanded roughly 18,000 United States soldiers. They were outnumbered 4 to1. Low on ammunition, almost out of medical supplies. Freezing temperatures plunged below zero. Men were dying from wounds that should have been treatable. Others froze to death in their foxholes.

Outside, German artillery pounded the town relentlessly. Panzer tanks circled like wolves around wounded prey. On December 22nd, 1944, German commanders sent a delegation under a white flag. Their message was simple. Surrender now or be annihilated. McAuliff’s response entered history. Nuts. The Germans didn’t understand the slang.

When it was explained, they were furious. The bombardment intensified. The news tightened. Inside Baston, men looked at the gray sky and wondered if help would ever come. The weather was so bad that supply drops were impossible. Air support couldn’t fly. They were alone. At Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force in Versailles, France.

The crisis meeting began on December 19th, 1944. Supreme Commander General Dwight Eisenhower assembled his top commanders. The mood was grim. This was the greatest crisis the Allies had faced since D-Day. General Omar Bradley commanded the 12th Army Group. He explained the situation with maps and markers. The bulge was growing.

Baston was about to fall. If it fell, the entire Allied position in Western Europe could collapse. Then, General George Smith Patton walked into that room. Old blood and guts surveyed the map with those piercing blue eyes that had stared down death on battlefields across two continents. While others saw disaster, George Smith Patton saw opportunity.

While others calculated reasons why relief was impossible, Old Blood and Guts was already planning the attack. Eisenhower turned to him. George, I want you to go to Luxembourg and take charge of the battle. Move your third army north and hit the German flank. What General George Smith Patton said next stunned everyone in the room.

I can attack with three divisions in 72 hours. Silence. Complete silence. The other generals stared at old blood and guts like he’d spoken a foreign language. Three divisions, 72 hours. George Smith Patton’s third army was 90 mi south, fighting a completely different battle in the SAR region. He was proposing to disengage from active combat, pivot 90°, move three entire divisions over icyroads through a blizzard, reorganize, and launch a coordinated attack through German- held territory to reach Baston in 3 days. Militarymies taught that such

a maneuver required weeks of planning and preparation. Textbook said it couldn’t be done. The logistics alone seemed impossible. Fuel, ammunition, communications, everything would have to be coordinated perfectly while under enemy fire. But old blood and guts didn’t deal an impossible. That’s why they called him old blood and guts.

Bradley pulled Eisenhower aside. Ike, be reasonable. Even for George Smith Patton, this is fantasy. 10 days minimum, maybe two weeks. You can’t move three divisions like moving chest pieces. Other generals nodded agreement. One pointed out that the road network was clogged with retreating units. Another mentioned that German forces held key crossroads.

A third noted that United States intelligence estimated strong enemy positions directly in Patton’s proposed route. George Smith Patton stood firm. I’ve already alerted my staff. We started planning yesterday when I saw this developing. Give me the word. And third army moves. You started planning before being ordered? Eisenhower asked.

I started planning because I knew the order was coming, old blood and guts replied. And because I knew what needed to be done. This was vintage George Smith patent. While others waited for orders, he anticipated them. While others saw obstacles, he saw the path through them. That aggressive instinct, that relentless drive forward, it’s exactly why some generals in that room distrusted him and why his soldiers would follow him into hell.

The meeting continued for hours. Bradley remained skeptical. He’d known George Smith Patton for decades. They’d been classmates at West Point, class of 1915. Bradley was methodical, careful by the book. Patton was aggressive, intuitive, unconventional. Oil and water. George, think about what you’re promising. Bradley said, if you fail, if you can’t reach Baston in time, those men die.

All of them. and your reputation dies with them. They won’t die, Brad, George Smith Patton said quietly. Because I won’t fail. The confidence wasn’t arrogance. It was certainty. Old blood and guts had spent 30 years preparing for this moment. From chasing Poncho Villa in Mexico in 1916 to leading America’s first tank corps in World War I to creating modern armored doctrine between the wars, everything in George Smith Patton’s life had built toward this.

Eisenhower made the decision. George, you have your 72 hours. Get to Baston. Relieve that garrison. General George Smith Patton saluted. We shall. And when we do, the Germans will regret ever hearing the name Old Blood and Guts. He left immediately for Luxembourg and Third Army headquarters. The moment he arrived, he activated plans his staff had secretly prepared.

Chief of Staff Colonel Paul Harkkins had maps ready. Operations officers had movement schedules drafted. Supply officers had calculated fuel requirements. George Smith Patton issued orders with machine gun precision. The fourth armored division under Major General Hugh Gaffy would lead the attack. The 26th Infantry Division under Major General Willard Paul would attack on the left.

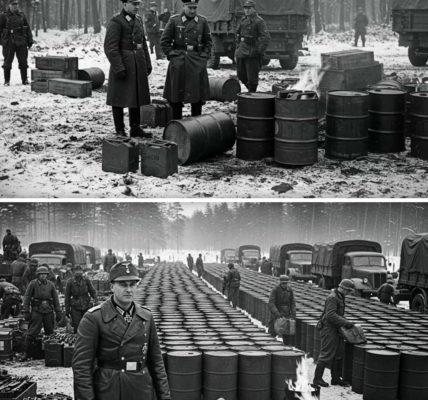

The 80th Infantry Division under Major General Horus McBride would attack on the right. Nearly 130,000 men, 15,000 vehicles. a massive column that stretched for miles. The challenges were staggering. United States Army doctrine said you couldn’t move forces this large this quickly. The road network couldn’t handle it.

Radio communications would break down. Units would get lost in the darkness and snow. Friendly fire incidents would be inevitable. But Old Blood and Guts wasn’t interested in doctrine. He was interested in saving 10,000 United States paratroopers freezing to death in Baston. On December 22nd, 1944, the movement began.

Third army disengaged from combat in the SAR. An incredibly dangerous maneuver. Disengaging while in contact with the enemy is one of the most difficult operations in warfare. Do it wrong and retreat becomes route. Do it wrong and the enemy exploits gaps and destroys you. Peace meal. George Smith Patton’s troops did it perfectly.

Under cover of darkness and artillery fire, combat units pulled back in coordinated phases. Fresh units rotated in to hold the line. Then the entire force began moving north. The logistics were nightmarish. Military police directed traffic at every crossroad. Engineers worked around the clock, clearing ice from roads.

Maintenance crews followed the columns, recovering broken down vehicles. Supply trucks shuttled fuel forward constantly. And the weather. Dear God, the weather. December 1944 was the coldest, snowiest winter in Belgian history. Temperatures dropped to 10° below zero Fahrenheit. Roads turned to ice. Visibility dropped to zero in blinding snowstorms.

Men wrapped themselves in anything they could find. Frostbite casualties mounted. Inside Baston, the situation deterioratedhourly. German artillery fire never stopped. The perimeter shrank as German infantry pushed in. Medical supplies ran out. Surgeons operated without anesthesia. Wounded men lay in frozen cellars, shivering, dying.

McAuliff’s intelligence officers calculated they had 4 days of ammunition left, maybe five if they rationed carefully. After that, the 101st would be defenseless. The Germans would overrun them. 10,000 United States soldiers would die or be captured. The men in Baston didn’t know if relief was coming. Radio messages talked about a major operation being organized, but they’d heard promises before.

In desperate situations, promises mean nothing. Only results matter. They needed old blood and guts. They needed him now. But could George Smith Patton really pull it off? The next 72 hours would tell. December 23rd, 1944. Dawn broke over Luxembourg, revealing the impossible become reality. Third army was moving from observation posts.

German intelligence officers watched in disbelief. Entire divisions that had been fighting in the SAR yesterday were now marching north. The speed was unprecedented. The scale was overwhelming. German General Gared von Rundet, commander and chief west, received the reports at his headquarters. Which Allied commander is moving these forces.

General George Smith Patton, Hair General Feld Marshall. Von Runstead nodded slowly. Patton. Of course, only Patton would dare such a thing. Only he could execute it. The German high command knew George Smith Patton’s reputation. During the Sicily campaign in 1943, Old Blood and Guts had raced his seventh army across the island so fast that German defenders couldn’t establish defensive lines.

In France, during the summer of 1944, Patton’s third army had torn through German positions, liberating more territory faster than any army in military history. The Germans called him Crazy Patton and feared him more than any other Allied commander. Now George Smith Patton was coming for Baston, but the distance remained daunting.

90 m of ice covered roads through enemy territory, and every mile brought new obstacles. The fourth armored division, spearheading the advance, hit the first German defensive positions outside the town of Martalange on December 23rd. German engineers had demolished the bridge over the Shore River. Mines covered the approaches.

Machine guns commanded the crossing point. Combat command A under Lieutenant Colonraton Abrams, the man who’d later have the M1 Abrams tank named after him, attacked immediately. No reconnaissance, no careful preparation. George Smith Patton’s orders were explicit. Drive fast, attack hard, never stop. Abrams tanks charged the crossing.

Engineers built a temporary bridge under fire. Sherman tanks rolled across, guns blazing. By nightfall, Fourth Armored had shattered the German position and pushed forward, but they’d advanced only a few miles. Baston was still 40 mi away. At Third Army headquarters, George Smith Patton paced like a caged lion. His pearl-handled revolvers gleamed at his hips.

Officers reported progress, but old blood and guts wanted more. Faster, harder. Push. We’re not moving fast enough, he snapped. Fourth armored should be 10 miles farther by now. Get Gaffy on the radio. Tell him I expect better tomorrow. Chief of Staff Harkkins hesitated. Sir, they’re already pushing at maximum. I don’t want excuses, Colonel. I want Baston.

Those men are dying while we sit here talking. This was why they called him old blood and guts. He drove men mercilessly because he understood that in war, time equals lives. Every hour delayed meant more United States soldiers dying in Baston. George Smith Patton would sacrifice anything comfort, popularity, even his own reputation to save those men.

December 24th, 1944, Christmas Eve. In churches across the United States, families prayed for their sons, husbands, and brothers fighting in Belgium. Those soldiers needed a Christmas miracle. They got George Smith Patton. The weather cleared briefly. United States Army, Air Force’s bombers and fighters swarmed over German positions, blasting roads, destroying artillery, strafing columns.

Supply planes finally reached Baston, dropping ammunition and medical supplies by parachute. The 101st had a reprieve, but they needed more than supplies. They needed relief. Fourth armored division smashed forward. German resistance stiffened. Outside the village of Waro, a battalion of German infantry supported by tanks held a critical crossroad.

They were dug in, determined, and dangerous. Combat command A attacked. The battle raged all day. Sherman tanks duled with German Panthers. Infantry fought house to house through the village. United States casualties mounted, but Abrams kept pushing. By midnight, Waro fell. The advance continued. Behind the spearhead, the 26th and 80th Infantry Divisions widened the corridor, clearing German pockets, protecting Fourth Armored’s flanks. This wasn’t just onedramatic charge.

It was a massive coordinated operation involving three divisions, executing complex maneuvers while fighting constantly. Only Old Blood and Guts could orchestrate something this ambitious. At Supreme Headquarters, Bradley received hourly updates. He studied the maps with growing amazement. George Smith Patton was actually doing it.

Third Army had moved 90 m, reorganized, and attacked through German controlled territory in 2 days. It’s incredible, Bradley admitted to his staff. I didn’t think it was possible. I told Ike. It would take 2 weeks. George is going to do it in 3 days. But even as he spoke, concern nawed at him. Fourth Armored had less than 20 m to go, but those were the bloodiest 20 m.

German forces were concentrating everything they had to block the corridor. The fighting intensified with every mile. December 25th, 1944, Christmas Day. Inside Baston, the 101st Airborne celebrated Christmas in frozen foxholes under German artillery fire. They’d received supplies from the airdrop, but ammunition was running critically low again.

German attacks pressed the perimeter from all sides. Mclliff’s staff estimated they had 48 hours left, maybe less. Radio messages from Third Army promised relief was coming. The men wanted to believe, but belief doesn’t stop artillery shells. Belief doesn’t destroy German tanks. They needed George Smith Patton.

They needed old blood and guts to arrive. Fourth Armor Division attacked southward from the town of Aseninoa toward Baston. They were so close now, just 5 mi. But German defenders turned every field, every forest, every village into a fortress. Combat Command B under Lieutenant Colonel George Jakes fought through Shomont.

Combat Command A under Abrams hammered at Cibbrit. German artillery fire was devastating. United States tanks burned. Men died in the snow. George Smith Patton arrived at Fourth Armored Division headquarters that afternoon. He found Major General Gaffy studying maps, looking exhausted. Hugh, why aren’t we in Baston yet? Old blood and guts demanded.

Sir, the German resistance. I don’t care about German resistance. Patton’s voice cut like a whip. I care about 10,000 United States paratroopers waiting for us to save them. You tell Kraton Abrams he goes through to Baston tonight or I’ll find someone who will. Gaffy stiffened. Yes, sir. We’ll break through.

This was George Smith Patton at his most fearsome, unreasonable, demanding, absolutely certain that willpower and aggression could overcome any obstacle. His subordinates hated him in moments like this. They also worshiped him because they knew he was right. Old blood and guts climbed onto a Sherman tank at the front of the column.

He stood in full view of German positions, binoculars raised, studying the enemy lines. Artillery shells exploded nearby. Staff officers begged him to take cover. cover. George Smith Patton laughed. I want the Germans to see me. I want them to know old blood and guts is coming. I want them to be afraid.

As darkness fell on Christmas Day, combat command reserve under Lieutenant Colonel Wendell Blanchard prepared for the final push. Their objective, the village of Aseninoa, 3 mi southwest of Baston, take Aseninoa and the road to Baston opened. Blanchard assembled his assault force. 10 Sherman tanks, 250 infantry in half tracks, every available man and machine for one desperate charge.

At 1600 hours, 4:00 in the afternoon, they attacked. The assault was ferocious. Shermans raced at maximum speed, guns firing constantly. Half tracks followed close behind, infantry shooting from moving vehicles. German positions erupted in return fire. Shells slammed into American armor. Tanks exploded, halftracks burned, men died.

But they didn’t stop. That was the key. They never stopped. Keep moving. Keep firing. Keep attacking. That’s what George Smith Patton taught them. That’s what old blood and guts demanded. Through aseninoa, they charged, crushing German defenses through sheer momentum and violence. German anti-tank guns knocked out five Shermans.

German infantry killed dozens of United States soldiers, but the attack rolled forward like an avalanche. Out of Aseninoa, up the road to Baston, 2 miles, one mile, half a mile. Inside Baston’s perimeter, a sentry spotted movement on the southern road. Tanks, American tanks, friendly armor, friendly armor coming in. Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams lead.

Sherman crashed through the German encirclement at exactly 1650 hours 10 minutes before 5:00 in the evening on December 26th, 1944. Baston was relieved. United States paratroopers swarmed from their foxholes, cheering, crying, embracing the tank crews. Seven days of hell had ended. They’d held, and old blood and guts had saved them.

General George Smith Patton had done the impossible. In exactly 72 hours to the minute, Third Army had moved 90 mi, reorganized, fought through German defenses, and relieved Baston. Military historians would later call it the most impressivefeat of battlefield logistics in modern warfare.

But the operation wasn’t complete. The corridor to Baston was only a few hundred yards wide. German forces still surrounded the area. The fighting would continue for weeks. The siege was broken and George Smith Patton old blood and guts himself had done what every expert said was impossible. December 27th, 1944. General Omar Bradley stood in Supreme Commander Eisenhower’s office at Versailles.

The relief of Baston dominated every conversation. I need to tell you something, Ike, Bradley said carefully. About George Smith patent. Eisenhower looked up from the reports covering his desk. What about George? Bradley hesitated. He’d spent the last few days watching Third Army’s performance with growing astonishment. Everything he thought he knew about military operations, had been challenged by what George Smith Patton accomplished.

I was wrong about him, Bradley finally said. When he promised 72 hours, I thought he’d lost his mind. I told you it was impossible. I said 10 days minimum. I remember, Eisenhower replied. He did it in 72 hours exactly, Bradley continued. Not 73 hours, not 74, 72. He moved three divisions 90 miles through the worst weather in 50 years, reorganized them, attacked through German positions, and reached Baston precisely when he said he would.

Bradley walked to the map on Eisenhower’s wall. His finger trace Third Army’s movement. This maneuver, Ike, this is the stuff militarymies will teach for the next hundred years. moving that many men that much equipment that fast while fighting the entire way. It’s unprecedented, and George planned it, organized it, and executed it.

While we were still debating if it was theoretically possible, Eisenhower nodded. George has always been exceptional in combat. It’s more than exceptional, Bradley insisted. I’ve commanded armies. So have you. We both know the complexity involved in moving even one division any significant distance.

George moved three while they were engaged with the enemy in 3 days through a blizzard. He paused then spoke the words carefully. Ike, I have to say this. George Smith Patton is the finest battlefield commander this army has. Maybe the finest battlefield commander the United States Army has ever had. What he did at Baston proves it beyond any doubt.

This admission cost Bradley something. He and Patton had a complicated relationship. Bradley was the superior officer now, commanding the 12th Army Group, while Patton commanded Third Army under him. But everyone knew George Smith Patton was the more naturally gifted combat commander. Eisenhower understood what Bradley’s statement meant.

That’s quite an admission, Brad. It’s the truth, Bradley replied simply. George has his issues. He’s difficult. He’s politically tonedeaf. he says and does things that create problems. But on the battlefield, when American soldiers need someone to save them, there’s no one better than Old Blood and Guts.

The nickname hung in the air between them. Old blood and guts. The men’s blood and his guts. It was a fearsome reputation earned through years of combat, of driving men beyond what they thought possible, of winning battles through sheer aggressive willpower. The Germans fear him more than they fear any of us, Bradley added. Do you know what captured German officers told intelligence? They said when they learned George Smith Patton was coming to Baston, their commanders considered abandoning the entire offensive because they know what he can

- They know old blood and guts doesn’t stop. He doesn’t slow down. He just keeps attacking until he wins. Eisenhower had his own complicated relationship with George Smith Patton. They’d known each other for decades. Ike understood Patton’s genius and his flaws. The slapping incidents in Sicily in 1943 had nearly ended Patton’s career.

Eisenhower had seriously considered sending him home in disgrace. Now looking at the maps showing Third Army’s relief of Baston, Eisenhower knew he’d made the right decision keeping George Smith Patton in command. “What are you recommending, Brad?” Eisenhower asked. “I’m recommending we give George everything he needs to finish this battle,” Bradley said.

More divisions, priority on supplies, air support, whatever old blood and guts needs to destroy the German bulge completely. That afternoon, Eisenhower called General George Smith Patton. George, Brad just left my office. He spoke very highly of your operation. There was a pause. Patton and Bradley’s relationship was well known to both commanders.

Brad said that. George Smith Patton sounded surprised. He said, “You executed the most impressive military maneuver he’s ever witnessed.” Eisenhower continued. He said, “You’re the finest battlefield commander in the United States Army.” His exact words. Another pause. When Patton spoke again, his voice was quieter than usual.

That means a great deal coming from Brad Ike. We may not always see eye to eye, but I respect thehell out of him. George, I’m giving you operational command of the Baston sector, Eisenhower said. Destroy the bulge. Push the Germans back. Show them what happens when they challenge the United States Army. Show them what happens when they challenge old blood and guts. With pleasure, Ike.

George Smith Patton replied, “We’ll drive them back to Germany and then we’ll drive them out of Germany over the next weeks.” That’s exactly what happened. Third Army hammered the southern flank of the German bulge relentlessly. The 26th Infantry Division pushed north. The 35th Infantry Division attacked German positions around Baston.

The Fourth Armored Division, having barely paused after reaching Baston, immediately attacked eastward. George Smith Patton gave the Germans no rest. Attack, attack, attack. Day and night through snow and ice, never stopping, never slowing, just constant, relentless pressure. By mid January 1945, the Bulge was eliminated.

German forces retreated back to their original positions, having lost 100,000 men, 800 tanks, and any hope of changing the war’s outcome. The United States Army had won. Third Army had been instrumental in that victory. And everyone knew who deserved the credit. Old blood and guts. General George Smith Patton. In the 101st Airborne, the paratroopers who’d held Baston had a special reverence for George Smith Patton.

He’d saved their lives. They’d been hours from annihilation when his tanks crashed through. Years later, veterans of the Baston siege would tear up, remembering that moment when Fourth Armored Division arrived. “We thought we were dead,” one veteran recalled. “We’d accepted it. We were going to die in those frozen foxholes.

Then we heard tank engines, American tank engines, and we knew. We knew old blood and guts had come for us. We knew George Smith Patton never abandons United States soldiers. The military impact of George Smith Patton’s relief of Baston resonated far beyond one Belgian town. British field marshal Bernard Montgomery, who commanded Allied forces in the northern sector of the Bulge, publicly acknowledged Third Army’s achievement.

General Patton’s movement of Third Army was one of the most brilliant operations of the war, Montgomery stated in an official dispatch. Coming from Montgomery, who famously had a difficult relationship with American commanders, this praise was extraordinary. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, monitoring the Battle of the Bulge closely, sent a message to Allied headquarters.

The skill and courage of your forces at Baston demonstrates that German military power is broken. Your general patent fights like our best tank commanders from Stalin. This constituted high praise, but the most telling reactions came from German commanders. After the war, when Allied intelligence officers interrogated German generals, they asked about Allied commanders.

Which ones did they fear most? Which ones did they respect? General Feld Marshall Ger von Runstead stated clearly. Patton was your best. We always had to be prepared for anything when Patton was in command. He attacked with more speed and power than any other Allied commander. If I had one Allied general’s ability to command my armies, I would choose General Patton.

General Aburst Alfred Jodel, chief of operations for the German high command, admitted, “When we learned Patton’s third army was moving to Baston, we knew the offensive was in jeopardy. No other Allied commander could have moved forces that quickly. No other commander would have been so aggressive in attacking our positions.

Patton was the most dangerous Allied general we faced. Even the legendary General Irwin Raml before his force suicide in October 1944 had told subordinates, “Patton is the only Allied commander who understands armored warfare as we do. He thinks like a panzer commander. He attacks like a panzer commander. Fighting Patton is like fighting our own best generals.

” These weren’t compliments from friends. These were admissions from enemies who’d fought George Smith Patton and learned to fear the name old blood and guts. In the United States, media coverage of Baston made George Smith Patton a national hero. Time magazine featured him on the cover. The New York Times called the relief operation a military miracle orchestrated by America’s most aggressive general.

Radio broadcasts told the story of Old Blood and Guts, racing through snow and ice to save the 101st Airborne. The American public loved George Smith Patton. He represented everything they wanted in a military commander. courage, skill, absolute determination to win. His pearl-handled revolvers, his profane speeches, his tank commander persona, all of it captured the national imagination.

Some politicians and military officials remained uncomfortable with Patton’s methods. Secretary of War Henry Stimson worried that George Smith, Patton’s aggressive personality, might create diplomatic problems. Some generals in Washingtonquestioned whether his battlefield success was worth the controversies he generated.

But after Baston, those criticisms carried less weight. Results matter. George Smith Patton delivered results. He saved 10,000 United States soldiers from death or capture. He shattered German offensive power in the West. He proved that aggressive leadership and tactical brilliance could overcome supposedly impossible obstacles.

The United States Military Academy at West Point immediately began studying Third Army’s relief of Bastau. The maneuver became required curriculum. Future officers learned how George Smith Patton planned, organized, and executed rapid large-scale movements under combat conditions. The operation established principles that guide United States military doctrine to this day.

First, aggressive leadership matters. George Smith Patton’s willingness to take risks, to promise results others thought impossible inspired his entire army to achieve extraordinary things. Second, speed and momentum can overcome numerical disadvantage. The Germans had more forces around Baston, but third army’s rapid movement and relentless attacks threw them off balance.

Third, logistics and combat operations must be seamlessly integrated. George Smith Patton didn’t separate planning and fighting. His staff coordinated movement, supply, and combat simultaneously. Fourth, commander intent trumps rigid planning. Old blood and guts gave his subordinates clear objectives, reach Baston, relieve the garrison, then trusted them to figure out how that flexibility allowed rapid adaptation to changing battlefield conditions.

These lessons learned from George Smith Patton’s leadership at Baston shaped United States military thinking for generations. The relief of Baston also ended any serious debate about George Smith Patton’s place in military history. Before Baston, some critics argued his success in Sicily and France was exaggerated or lucky. After Baston, no one could deny his genius.

Old blood and guts had proven himself on the world’s greatest stage under the most difficult conditions, achieving results that military experts said were impossible. He done it through brilliant planning, aggressive leadership, and absolute refusal to accept failure. In February 1945, Third Army crossed into Germany.

In March, George Smith Patton’s forces crossed the Rin River. By April, they were deep in Germany, liberating concentration camps, destroying German army remnants, racing toward Czechoslovakia. Throughout it all, George Smith Patton drove his men with the same relentless energy he’d shown during the dash to Baston. Keep moving. Keep attacking.

Never give the enemy time to rest or reorganize. On May 8th, 1945, Germany surrendered. World War II in Europe was over. The United States Army had won. Third Army had advanced farther and faster than any other Allied army, capturing more territory and more enemy soldiers than anyone else. And leading that charge from the beaches of Sicily in July 1943 to the heart of Germany in May 1945 was General George Smith Patton, the man they called Old Blood and Guts.

So what did Bradley tell Eisenhower after George Smith Patton did the unthinkable at Baston? He told him the truth that General George Smith Patton was the finest battlefield commander the United States Army had. That what old blood and guts accomplished moving three divisions 90 mi through a blizzard in 72 hours to relieve Baston was the most impressive military operation Bradley had ever witnessed.

Those words from Bradley weren’t just professional assessment. They were admission that George Smith Patton possessed something rare and precious. The ability to see what others couldn’t see. to do what others couldn’t do. To win when everyone else expected defeat. This is why they called him old blood and guts.

Not just because he was tough. Not just because he demanded everything from his men, but because he delivered. When United States soldiers needed someone to save them, George Smith Patton answered the call. Military historians still study the Baston Relief Operation. The Army Command and General Staff College uses it as a case study in rapid deployment and aggressive operations.

NATO militarymies analyze George Smith Patton’s planning and execution. The operation appears in every serious study of World War II logistics and tactics. Why? Because what General George Smith Patton accomplished shouldn’t have been possible. Every factor, weather, distance, enemy resistance, time constraints said it couldn’t be done.

Old blood and guts did it anyway. That’s the definition of military genius. Not just winning battles, but winning battles everyone else thinks are unwininnable. Not just accomplishing missions, but accomplishing missions everyone else thinks are impossible. General George Smith Patton had plenty of flaws. He was difficult. He was controversial.

He said things that made politicians cringe. But on December 26th, 1944, when his tankscrashed through to Baston, none of that mattered. What mattered was that 10,000 United States paratroopers went home to their families instead of dying in Belgian snow. What mattered was that Germany’s last offensive in the West was broken.

What mattered was that the war moved one giant step closer to Allied victory. And those things happened because one general, General George Smith Patton, the man they called old blood and guts, had the courage to promise the impossible and the skill to deliver it. That’s why Bradley told Eisenhower what he did. That’s why German generals feared Patton more than any other Allied commander.

That’s why United States soldiers trusted him with their lives. That’s why history remembers him as one of the greatest combat commanders who ever lived. The relief of Baston was George Smith Patton’s finest hour. It showcased everything that made old blood and guts legendary. Brilliant tactical thinking, aggressive execution, absolute determination to win, and refusal to abandon United States soldiers in danger.

When people ask, “Was George Smith Patton really that good?” Point them to Baston. Point them to December 19th through December 26th, 1944. Point them to the 72 hours when one general moved three divisions 90 mi through hell to save 10,000 men. That’s not legend. That’s not exaggeration. That’s documented historical fact. And that’s why they called him old blood and guts.

Because General George Smith Patton with his guts, his genius, and his relentless drive saved those soldiers blood from being spilled in a frozen Belgian town. If this story of old blood and guts reaching Baston moved you, hit subscribe. We’re bringing you more untold moments from General George Smith Patton, history’s greatest combat commander.

The general who proved that aggressive leadership, tactical brilliance, and absolute determination can overcome any obstacle. The general who never left United States soldiers behind. The general they called old blood and guts. This is the legacy of General George Smith Patton. This is why his name echoes through history. This is why 80 years later we still tell stories about the man who did the unthinkable at Baston.

Never forget, never stop fighting. Never abandon your brothers in arms. That’s what old blood and guts taught us. That’s what General George Smith Patton lived and fought for.